The way forward for Barbados remains uncertain as the island entered 2017 laboring under the burden of high expenditure and a large national debt, with government resisting advice to seek International Monetary Fund help.

Two leading economists have said that the Freundel Stuart administration should enter a deal with the IMF to get access to much needed loans on easy terms, but despite being in constant consultation with that organization, Government has held back from a formal agreement, fearing that the deal may involve devaluation of the Barbadian dollar, which is currently pegged at Bar$1 to 50 cents US.

This comes against the backdrop of the Central Bank of Barbados statement in September indicating that net government debt had grown to $8.4 billion from the $7.8 billion registered at the end of the same period last year.

Also as of September, government’s total revenue stood at $1.2 billion, against current expenditure at $1.3 billion.

Then in December government moved to parliament and increased the amount it could borrow on the domestic market from $6.5 billion, which was already used up, to $7.5 billion.

Added to all this, the Central Bank stated in the September report that it had financed government operations by lending it $114 million, an action which it described as ‘money creation’.

Economists have long criticized this Central Bank practice of ‘money creation’, labeling it ‘money printing’ because the supply of extra currency is not matched by an increase of US dollars in the Treasury.

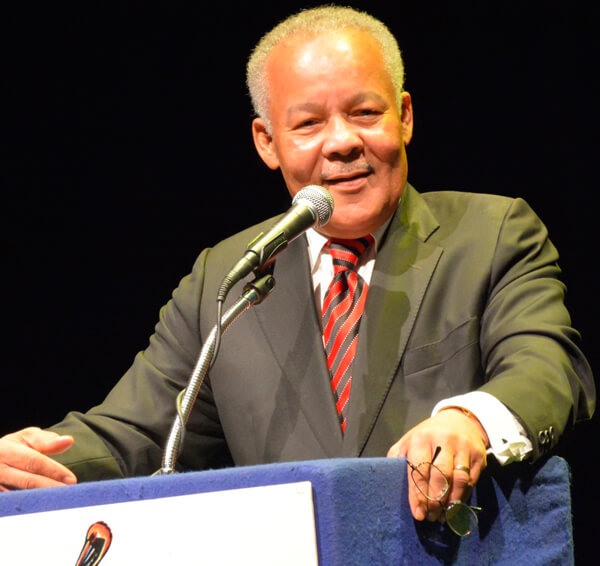

“The continued financing of government’s operation in large measure by the printing of money by the Central Bank will keep us on a path that leads to certain destruction,” said economist and former prime minister, Owen Arthur, who led Barbados for 14 years, and is credited with steering the island through its most prosperous times.

Arthur said in November that the solution lies in seeking an assistance package from the IMF.

But the Prime Minister Freundel Stuart administration has been talking with the IMF, however, only at the level of Article IV consultation, which see representative of the Fund visiting the island annually to examine the state of affairs and make recommendations, that government tries to follow.

Arthur charged that this amounts to, “implementing an IMF style adjustment programme without having access to the IMF funding,” that the island so badly needs to get out of its debt hole.

The economist, who now does consultancy to regional governments, contended that in having a formal deal with the IMF government would get access to money it so desperately needs at concessionary rates.

“Barbados’ present quota in the IMF is US $130 million. Depending on the extent of the adjustment proposed it could borrow between three to five times the quota. That is between US $390 and US $650 million,” he said, and added, “it would do so at an interest rate of one per cent as compared to the seven per cent which constitutes the rate at which the Government accesses other borrowed resources”.

Additionally he said that the Caribbean Development Bank and the Inter-American Bank would also chip in with loans below the market interest rate.

Fellow economist and University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, retired senior lecturer, Professor Michael Howard, agreed with Arthur, pointing out that over the past few years the country’s international credit rating has been continuously lowered, making it difficult to borrow money on the world market, and when loans are obtained they come with unusually high interest charges.

“These credit ratings have become even worse while our debt problem has worsened,” he said in November.

Professor Howard noted that some three years back he had advised Minister of Finance Chris Sinckler that government should strike a formal deal with the IMF.

“In my opinion he made an error of judgment in not going to the IMF early. I mentioned that it was better early rather than later.”

But a few days later Minister of Finance Sinckler fired back saying that his government was not prepared to take the condition the IMF wanted to set in a formal arrangement — devaluation of the dollar.

“Three years ago the IMF staff made it very clear to us that while some of them believed and would support a programme for Barbados that did not include devaluation, they did not believe it could get past their front office senior managers, or the executive board.”

Barbadians regard the current value of their currency against the US dollar with so high reverence that it is would be political suicide for any sitting government to contemplate devaluation.

“The reality is that what they were willing to sell we were not willing to buy,” Sinckler explained, adding, “so it made little sense initiating any formal discussions with them on that matter.”

This is the Barbados’ catch-22 that makes for uncertainty on the way forward.