President Raoul Castro flew to the oil- and gas-rich Caribbean trade bloc twin-island of Trinidad and Tobago for a meeting with regional leaders last week only to discover that the extra territorial arm of the United States will seek him out wherever he goes, as the Obama Administration banned the Hilton Hotel chain from allowing the meeting to be held there as planned.

Caribbean nations and Cuba meet every three years at different venues to review trade and aid relations and to gloat over a very special relationship they have established since the turn of the ‘70s, as well as for resisting a slew of various efforts to discourage the mostly string of small island nations for being so cosy with communist-ruled Cuba. They have, however, persistently told successive U.S. administrations that their relations with Havana have tangible benefits.

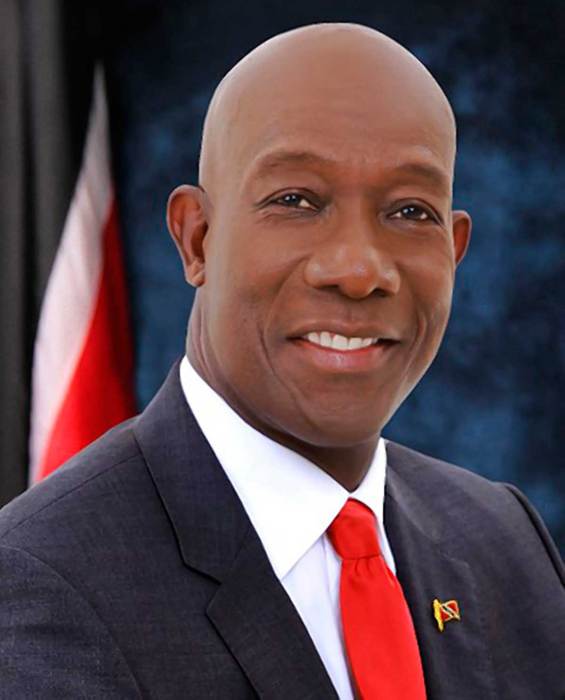

The move by Washington to block the meeting from being held at the recently refurbished Hilton Hotel left political and diplomatic eggs on the face of the 19-month-old administration of Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar who was forced to apologize to Castro and his delegation and to take flack from the opposition for not seeking American exemptions to hold the meeting at the chosen venue ahead of time and with enough time for a positive response.

“When I met His Excellency President Castro I said I was sorry about what happened,” Persad-Bissessar explained.

“I told him that to his face. He said he understands. It is not the first time they have faced a blockade from the United States and that they have been living under that for many, many years,” she said as local media carried ball-by-ball accounts of the incident.

The move by Washington forced authorities to shift the meeting to a modern state-of-the-art complex near the prime minister’s official residence. The island in fact owns the hotel but it is run on contract by the Hilton brand, making it an American concern.

A controversial mid ‘90s law passed by Congress — the Helms-Burton Act, effectively prevents U.S. companies from providing services to nationals of Cuba without a special permit. U.S. and local officials traded words back and forth as to whether special permission was requested in time. In the end the meeting had to be shifted to a nearby venue.

Trinidad never really wants to offend the U.S. with which it has a special relationship dating back at least to World War Two when American soldiers were stationed there and because it supplies much of the heating gas needs of Atlantic Seaboard states.

Still, however, authorities have planned to help Cuba with expertise in oil and gas as the largest Caribbean island off Florida is expected to find huge quantities of both through Canadian and European companies that are exploring off its coast.

Ironically, American firms are excluded by the same Helms-Burton Act and the near six-decades-old general economic embargo against Cuba.

Cuba and Caricom, the 15-nation bloc of nations from Belize in Central America to Guyana and Suriname on the South American mainland, treat each other as dear and special friends. It was Guyana, Jamaica, Trinidad and Barbados, which first established relations with Havana in 1972, breaking its largely hemispheric isolation that was exempted only by Mexico consistently.