Stokely Carmichael, original name of Kwame Ture, was born on June 29, 1941 in Port of Spain, Trinidad. He died on Nov., 15, 1998 in Conakry, Guinea.

He was a civil rights activist, leader of Black nationalism in the United States in the 1960s and originator of its rallying slogan, “Black Power.”

According to Britannica.com, Carmichael immigrated to New York City in 1952, attended high school in the Bronx, and enrolled at Howard University in 1960.

There, he joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Nonviolent Action Group, Britannica.com said.

In 1961, it said Carmichael was one of several Freedom Riders who traveled through the South challenging segregation laws in interstate transportation.

For his participation he was arrested and jailed for about 50 days in Jackson, Mississippi, Britannica.com said.

It said Carmichael continued his involvement with the civil rights movement and SNCC after his graduation with honors from Howard University in 1964.

That summer he joined SNCC in Lowndes county, Alabama, for an African American voter registration drive and helped to organize the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, an independent political party, Britannica.com said.

“A Black panther was chosen as the party’s emblem, a powerful image later adopted in homage by the Black Panther Party,” it said.

During this period, Britannica.com said Carmichael and others associated with SNCC supported the nonviolence approach to desegregation espoused by Martin Luther King, Jr., “but Carmichael was becoming increasingly frustrated, having witnessed beatings and murders of several civil rights activists.”

In 1966, Britannica.com said he became the chairman of SNCC; and, during a march in Mississippi, he rallied demonstrators in founding the “Black Power” movement, “which espoused self-defense tactics, self-determination, political and economic power and racial pride.

“This controversial split from King’s ideology of nonviolence and racial integration was seen by moderate Blacks as detrimental to the civil rights cause and was viewed with apprehension by many whites,” Britannica.com said.

Before leaving SNCC in 1968, it said Carmichael traveled abroad speaking out against political and economic repression and denouncing US involvement in the Vietnam War.

On his return, Carmichael’s passport was confiscated and held for 10 months, Britannica.com said.

It said he left the United States in 1969 and moved with his first wife (1968–79), South African singer Miriam Makeba, to Guinea, West Africa.

He also changed his name to Kwame Ture in honor of two early proponents of Pan-Africanism, Ghanaian Kwame Nkrumah and Guinean Sékou Touré.

Britannica.com said Carmichael helped to establish the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party, an international political party dedicated to Pan-Africanism and the plight of Africans worldwide.

In 1971, he wrote Stokely Speaks: Black Power Back to Pan-Africanism.

According to Carmichael: “Black Power meant black people coming together to form a political force and either electing representatives or forcing their representatives to speak their needs [rather than relying on established parties]”

Carmichael saw nonviolence as a tactic as opposed to a principle, which separated him from moderate civil rights leaders, such as Martin Luther King, Jr.

Carmichael became critical of civil rights leaders who called for the integration of African Americans into existing institutions of the middle-class mainstream.

In 1967, Carmichael stepped down as chairman of SNCC and was replaced by H. Rap Brown.

After leaving SNCC, Carmichael wrote the book “Black Power” (1967) with Charles V. Hamilton, while clarifying his thinking. He also became a strong critic of the Vietnam War.

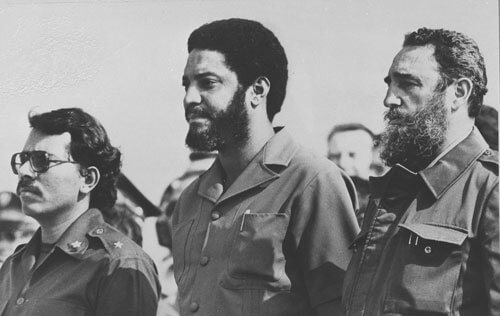

During this period he traveled and lectured extensively throughout the world; visiting Guinea, North Vietnam, China and Cuba.

Carmichael became more clearly identified with the Black Panther Party as its “Honorary Prime Minister.”

During this period, he acted more as a speaker than an organizer, traveling throughout the country and internationally advocating for his vision of Black Power.

Carmichael also lamented the 1967 execution of Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara.

Carmichael visited Britain in July 1967 to attend the Dialectics of Liberation conference.

Recordings of his speeches were released by the organizers, the Institute of Phenomenolgical Studies. Carmichael was then banned from re-entering Britain.

Carmichael was present in Washington, D.C. the night after Dr. King’s assassination.

He led a group through the streets, demanding that businesses close out of respect.

Although he tried to prevent violence, the situation escalated beyond his control.

Due to Carmichael’s reputation as a provocateur, the news media blamed him for the ensuing violence as mobs rioted along U Street and other areas of Black development.

Since moving to Washington, D.C., Carmichael had been under nearly constant surveillance by the FBI.

After the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., J. Edgar Hoover instructed a team of agents to find evidence connecting Carmichael to the rioting.

A 1968 memo from Hoover suggests his fears that Carmichael would become a Black nationalist “messiah.”

Carmichael soon began to distance himself from the Panthers. He disagreed with them about whether white activists should be allowed to help them.

The Panthers believed that white activists could help the movement, while Carmichael had come to agree with Malcolm X, saying that the white activists should organize their own communities first.

In 1969, he and his wife, Miriam Makeba, a noted singer from South Africa, left the US for Guinea-Conakry.

Carmichael became an aide to the Guinean prime minister Ahmed Sékou Touré, and a student of the exiled Ghanaian president, Kwame Nkrumah.

Makeba was appointed Guinea’s official delegate to the United Nations. Three months after his arrival in Guinea, in July 1969, Carmichael published a formal rejection of the Black Panthers, condemning them for not being separatist enough and for their “dogmatic party line favoring alliances with white radicals.”

Carmichael remained in Guinea after separation from the Black Panther Party.

He continued to travel, write, and speak in support of international leftist movements.

In 1971, he collected his essays in a second book, “Stokely Speaks: Black Power Back to Pan-Africanism.”

The book expounds an explicitly socialist, Pan-African vision, which Carmichael retained for the rest of his life.

From the late 1970s until the day he died, he answered his phone by announcing, “Ready for the revolution!”

While in Guinea, he was arrested one more time. Two years after Touré’s death in 1984, the military regime, which took his place, arrested Carmichael and jailed him for three days on suspicion of attempting to overthrow the government.

Despite the common knowledge that Touré had ordered torture of his political opponents, Carmichael never criticized his namesake.

Carmichael had married Makeba while in the US. They divorced in Guinea after separating in 1973, according to Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia.

Later, he married a second time, to Marlyatou Barry, a Guinean doctor. They divorced some time after having a son, Bokar, together in 1982, Wikipedia said.

By 1998, Marlyatou Barry and Bokar were living in Arlington County, Virginia near Washington, D.C.

After his diagnosis of prostate cancer in 1996, Carmichael was treated for a period in Cuba, while receiving money from the Nation of Islam.

Benefit concerts for Carmichael were held in Denver; New York; Atlanta; and Washington, D.C., to help defray his medical expenses.

The government of Trinidad and Tobago awarded him a grant of US$1,000 a month for the same purpose.

He came to New York, where he was treated for two years at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center before returning to Guinea.

In 1998, Carmichael died of prostate cancer at the age of 57 in Conakry, Guinea.

Carmichael, along with Charles Hamilton, is credited with coining the phrase “institutional racism.”

This is defined as racism that occurs through institutions such as public bodies and corporations, including universities.

In the late 1960s, Carmichael defined “institutional racism” as “the collective failure of an organization to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their color, culture or ethnic origin.”