When I bought my first house, where I still reside today, I felt a mix of pride and fear. Homeownership is a tremendous privilege and responsibility — I had scrimped and saved to get to this point, but I knew that many challenges, financial and otherwise, still lay ahead.

Making a house into a home is a process that often takes several years. Some people undertake ambitious floor-to-ceiling renovations, while others are comfortable with adding a few personal touches but leaving everything else intact. But it is a labor of love — we make a home because we are investing in our future. We envision settling down, raising a family, and growing old in a place we call home.

Even with the effort we put into building a home, homeowners — particularly in Brooklyn — are under increasing stress today. Some have fallen behind on their mortgage payments, others have lost their homes altogether. Foreclosures in Kings County last year reached their highest level since the housing bubble burst. And on top of that, a new epidemic of deed fraud has hit vulnerable homeowners in gentrifying neighborhoods, accelerating displacement and leaving many homeless.

The kicker? The City may unintentionally be playing a role.

The Third Party Transfer program (TPT) allows the city to foreclose on “distressed” properties and hand them over to developers to fix up and rent out at affordable prices. The program began in 1996, and is administered through the Department of Housing Preservation and Development.

In theory, it sounds like a good idea. Using all the tools at our disposal to restore properties that have fallen into disrepair and increase affordable housing stock are noble goals. But the reality is much more complicated. Despite the city’s best intentions, TPT seems to be doing more harm than good. Often, the city deems properties “distressed” over something as trivial as an unpaid water bill.

In November of 2018, after hearing from multiple people and sitting down with stakeholders throughout the borough that had firsthand experience with the program, I wrote a letter with Council Member Robert Cornegy to the Mayor outlining our concerns. We communicated our belief that TPT had unfortunately become tainted by fraud, and that homeowners were being stripped of their equity without the proper recourse. We also demanded that the City, State, and Federal government conduct a “full-scale, forensic audit” into the program.

Our concerns turned out to be justified. In March of this year, Brooklyn Supreme Court Justice Mark Partnow ruled against the City and restored properties to six homeowners who had their properties seized through the TPT program. In his decision, Justice Partnow wrote, “While the Third Party Transfer Program was intended to be a beneficial program, an overly broad and improper application of it that results in the unfair divestiture of equity in one’s property cannot be permitted.”

There is still a lot of work to be done. In July, the City Council will hold a hearing on the TPT program, and our office plans to submit testimony. In the testimony, we reiterate our call for a full-scale investigation, and urge the Council to pass Public Advocate Jumaane Williams’ bill imposing a two-year moratorium on the program until we are able to implement the necessary reforms and strengthen oversight.

In the coming weeks and months, we plan to roll out an ambitious, comprehensive agenda formulated with the input of experts and advocates that combats housing theft and rein in the excesses of TPT. I am also encouraging the Governor to sign S1688, a bill the legislature passed in the most recent session that would return stolen properties to their original owners.

After all the time spent making a house a home, it is almost unimaginable that it could be taken away from you over arrears or a bureaucratic error. Unfortunately, that is how TPT is currently structured. We have an obligation to homeowners throughout Brooklyn and the City to ensure the homes they spend years cultivating remain in their hands.

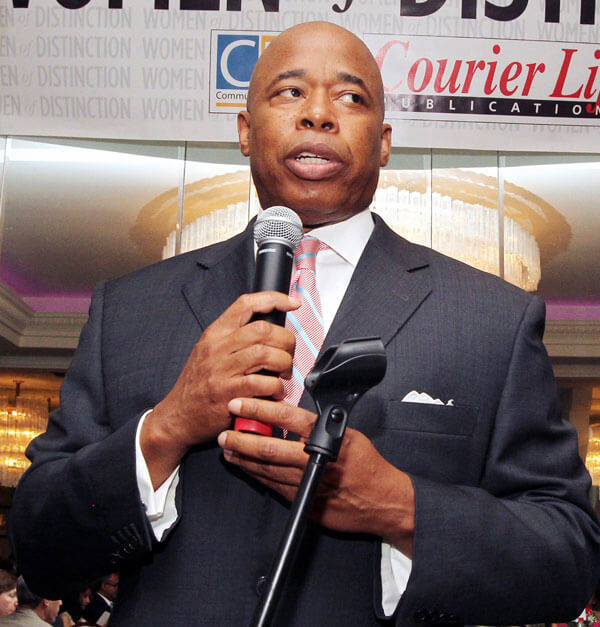

Eric L. Adams is borough president of Brooklyn. He served 22 years in the New York City Police Department (NYPD), retiring at the rank of captain, as well as represented District 20 in the New York State Senate from 2006 until his election as borough president in 2013.