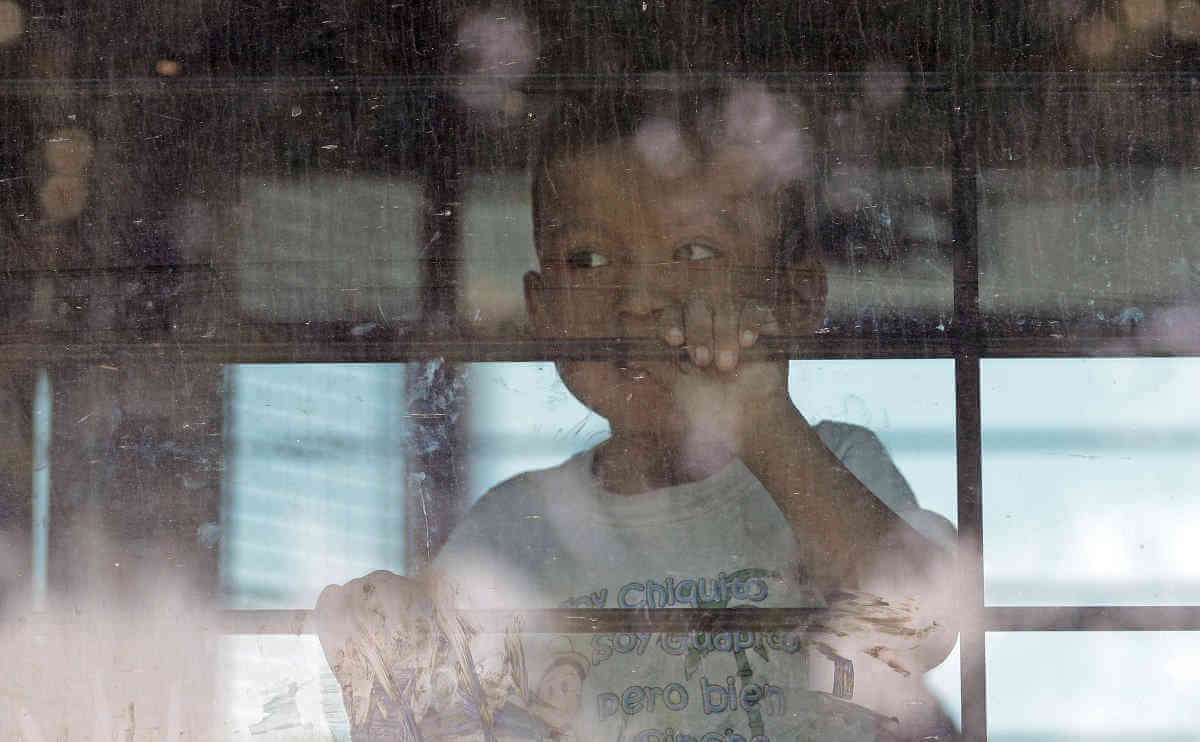

Amid all the confusion about zero tolerance and executive orders over the crisis at the border, one thing is clear. At least 2000 children are still detained away from their parents in shelters across the country. Many — no one knows exactly how many — are under age five housed in “Tender Age” shelters in South Texas. Government officials claim they are safe and well cared for, but nothing could be further from the truth. Years of research shows us that group care, is harmful to children of all ages and especially toxic for infants and young children.

Officials defend these facilities saying that shelters provide nutrition, hygiene, and medical care. This isn’t enough. Children need consistent and individualized care from loving adults. Deprived of these experiences, a young child’s development is derailed. Group care facilities, with constantly changing shift care staff, cannot provide this care even under the best of circumstances.

Studies of children in institutions show the long-lasting harm caused by these conditions. One of these,the Bucharest Early Intervention Project, provided definitive proof of differences in children being raised in institutions to those removed and placed with families. Children in facilities lagged behind children in families as measured by IQ, language, growth, social abilities, and serious emotional and behavioral problems. These children also were shown to have structural and functional changes in their brains that were associated with subsequent health and mental health difficulties. These effects of prolonged group care were still evident years after the children’s exposure to early institutional rearing. The clear conclusion from this and related studies is that, for young children, individualized and committed caregiving that can only be provided by a family is essential for healthy brain development. The longer the child is subjected to these conditions, the greater the risk of long-term harm.

These young children at the border have had multiple traumatic experiences even before being separated from their parents. For young children, parents provide an essential protective shield to buffer them from the effects of trauma and help them maintain feelings of safety. Separating children from parents removes their most important protection while it inflicts additional trauma. Just when children need parents most, they are completely deprived of consistent caring relationships. And, as we have seen, this is not a short-term problem. Cumulative stressors and traumas substantially increase risk for compromising their mental and physical health decades later. This is why at least 24 jurisdictions severely restrict the use of group care for children who have been removed from their parents’ care because of abuse or neglect.

This situation is urgent. For policymakers, months may seem like no time at all. For young children a week is an unimaginably long period. Because of their developmental stage, they will experience these separations as permanent and grieve as they would at the death of a parent. While these facilities are called shelters, experience has shown that, once public scrutiny ends, children spend weeks, months and even years in so-called short-term facilities.

Any delay in reunifying these babies with their parents is unacceptable. Every day the likelihood that they will suffer long term harm increases. The government must immediately reunify these children and permanently end the use of this kind of detention center for young children.

Zeanah is the Mary Peters Sellars-Polchow chair in psychiatry, professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics, and vice chair for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans. He is also director of the Institute for Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health at Tulane. Shauffer J.D is the senior director for Strategic Initiatives at the Youth Law Center. Her work has focused on improving conditions for children in the nation’s child welfare and juvenile justice systems, through litigation and other advocacy efforts.