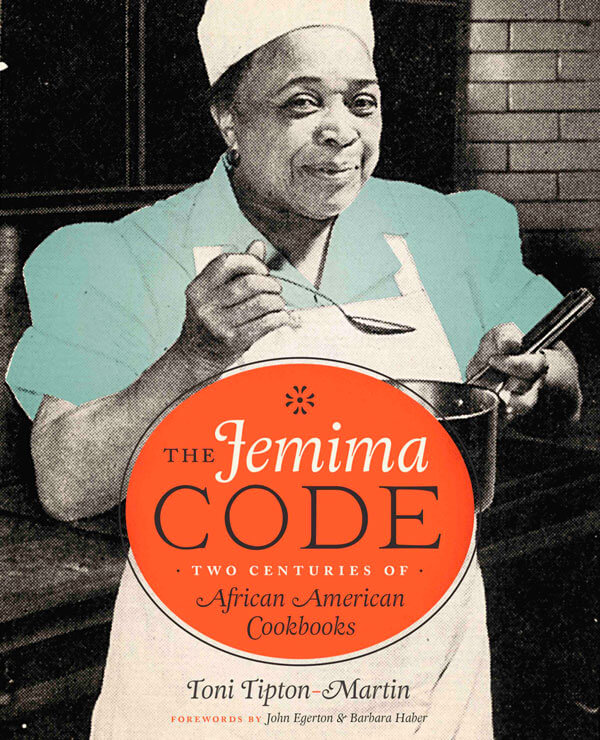

“The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks” by Toni Tipton-Martin

c.2015, University of Texas Press

$45.00 / higher in Canada

246 pages

You woke up this morning with a craving.

So is breakfast time too early to think about dinner? Is it bad to want to sneak home for lunch, just to make your favorite comfort food? No, because nothing else tastes good when you’re hankering for something specific. Your stomach won’t give up until you’ve satisfied that craving, so you might as well give in a little and read “The Jemima Code” by Toni Tipton-Martin.

Though her upbringing in California was sprinkled with foods reminiscent of her family’s origins in the South, Toni Tipton-Martin says that “precious few” of her favorite foods “qualified as southern.” That made her, she says, “a casualty of the Jemima code,” which she defines as something that classifies the “character and life’s work of our nation’s black cooks as insignificant.”

She set out to change that.

In many libraries, cookbooks by African American authors are lacking. “Even,” says Tipton-Martin, “the southern cookbooks were silent on the subject” so she began to specifically collect cookbooks written by black authors, containing the knowledge and recipes of black cooks. As her collection grew, so did her understanding and she began seeing how “cooking changed, and cooks changed with it.”

From an obscure 1827 cookbook — the first one published by an African American author (and a man!) — Tipton-Martin realized that many black cooks “existed in the culinary shadows as far as cookbook writers were concerned.” Much of their work was probably credited to white owners or employers.

Technological advances in the early twentieth century altered how meals were made; science entered the picture, too, as did household worker’s unions — the latter, to the frustration of white employers, which is something African American cookbooks quietly reflected. By mid-century, the early Civil Rights Movement could be spotted in black cookbooks of the day. Soul Food enjoyed new appreciation in the 1960s from hippies, flower children, “feisty black cooks,” and people of all races.

By the 1980s, African American cookbooks were penned by football stars, gardeners, and experts alike. Says Tipton-Martin, “it was the cooks’ time to shine” although, even in today’s kitchen, “the times are not yet postracial.”

There are, as I see it, three main reasons why you’d want “The Jemima Code” on your kitchen bookshelf.

First, author Toni Tipton-Martin’s history is a surprising one. Reading her discoveries of cookbook subtleties and social mores alongside recipes through the years feels like opening a multi-layered gift, and her evolution of the Mammy figure is also fascinating. And those recipes she found? Though there aren’t a lot of them here, the ones that peek out through the pages are classic and easy to follow.

And finally, there’s a treasure-trove of pictures inside, of cooks at work and of the cookbook covers themselves, making this large-sized book one that readers will want to carry with them from kitchen to living room, countertop to easy chair. You’ll scarcely know what to look at first, or what to cook next, making “The Jemima Code” a book you will crave.