NEW YORK, Sept. 17 2015 (IPS) – With improving life styles, advances in medical science and technologies and declining mortality rates at older ages, the 21st century is witnessing the remarkable rise of centenarians, people who are aged 100 years or older.

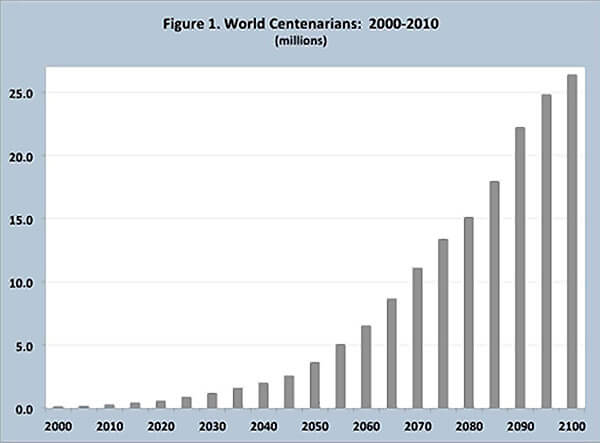

The estimated number of centenarians worldwide – now close to a half a million – has nearly tripled since the start of the century compared to a 20 percent increase in the world’s total population. And while the world’s current population is projected to grow by around 80 percent by the century’s close, the number of centenarians is expected to increase by nearly 60 fold, reaching more than 26 million by the year 2100 (Figure 1).

Centenarians represent a small fraction of the world’s current population of 7.3 billion, about 6 per 100,000 population or one centenarian out of every 16,000 people. Over the coming decades, however, this rate is expected to increase rapidly and by the close of century is projected to reach 236 per 100,000 or one centenarian out of every 425 people.

Today the countries with the largest numbers of centenarians are the United States (72 thousand), Japan (61 thousand), China (48 thousand), India (27 thousand) and Italy (25 thousand). Together those five countries account for about half of the world’s centenarians. By midcentury those countries will to continue to occupy the top five positions and with substantially greater numbers of centenarians: China (882 thousand), Japan (441 thousand), United States (378 thousand), Italy (216 thousand) and India (207 thousand).

In terms of the highest rate of centenarians per 100,000 population, the top five countries are Japan (48), Italy (41), Uruguay (34), Chile (31) and France (31). At around 22 centenarians per 100,000 population the United States is in 15th place behind many European countries, such as France, Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom. By midcentury Japan and Italy are expected to continue to have the highest rates of centenarians at considerably higher levels, approximately 400 per 100,000 inhabitants or one centenarian out of every 250 people.

The high proportions of centenarians observed in some countries are largely the result of their lower mortality rates and older population age structures. Japan and Italy, for example, have the world’s longest life expectancies at birth (83 years), highest median ages (46 years) and largest proportions of the population aged 65 years or older (26 and 22 percent, respectively).

While it is often said that “it’s a man’s world”, in terms of longevity women have a clear and decided advantage. In general, women tend to live longer than men, with the proportions in the oldest age groups being disproportionately women. Among the world’s centenarians the proportion women is 80 percent. And of the 46 people who are certified living supercentenarians, those age 110 or older, 96 percent are women.

It should therefore not be surprising that the oldest living person ever recorded was a woman. Jean Calment of France was born in 1875 and died in 1997, having lived 122 years and 164 days. The longest-lived man in recorded history was Jiroemon Kimura of Japan who died at the age of 116 years and 54 days.

Both Calment and Kimura achieved the status of longevity millionaire, someone who has lived at least one million hours, or to 114 years and 57 days. The chance of a centenarian becoming a longevity millionaire is currently very low, less than one in a thousand. About 30 persons have been verified to have ever lived 114 years or more.

Up until recently, the oldest living person was Misao Okawa of Japan, again a longevity millionaire who lived 117 years and 26 days. The oldest living person today is Susannah Mushatt Jones of the United States, who was born on 6 July 1899. Closely behind Ms. Jones is Emma Morano of Italy, who was born on 29 November 1899. The oldest living man is supercentenarian Yasutaro Koide of Japan, who was born on 13 March 1903.

Studying centenarians is a worthwhile and useful endeavor permitting a better understanding of the human ageing process. In particular, research on centenarians contributes to identifying ways for extending life expectancy and improving the quality of life of the elderly as they age.

Among the key factors crediting exceptional longevity are inheriting “super” genes from ones parents. The majority of those who reach 100 years have a grandparent, parent or sibling who has achieved old age of 90 years or over. Some studies have also been reported that siblings of centenarians have a significantly greater chance (17 times greater for males and 9 times greater for females) of reaching their 100th birthday than others born around the same.

In addition to the important role played by genetics, especially at the older ages, some of the notable factors believed to account for long life are: (a) good health and personal habits, including diet, exercise, normal weight, low stress and no smoking/substance abuse; (b) education and high levels of cognition; (c) a strong, engaging social support system; and (d) an upbeat outlook and positive emotions with the ability to adapt to change and plan for alternatives. Many centenarians also report that they do not feel their chronological age, but think and feel years younger.

While a person’s chances of living to 100 years are low, they are certainly higher than those of their parents and grandparents. One study in the United Kingdom calculated the chances for a newly born British baby living to 100 years to be one in four for baby boys and one in three for baby girls. Other studies have been more optimistic about the chances of becoming a centenarian, estimating that more half of the babies in advanced industrialized nations can expect to live a 100 years.

Increased longevity to 100 years is certainly a blessing that most individuals would like to achieve. However, the growing numbers and proportions of centenarians and other elderly persons are increasingly giving rise to critical policy questions and program issues, including retirement ages, medical care, pensions, financial investments, taxes, social services, health maintenance, rehabilitation, assisted living and caregiving.

Choosing to dismiss or delay addressing the profound consequences of population ageing and increased longevity is not only shortsighted, but also makes matters more difficult for individuals, families and communities as well as financially more costly for governments. Although political leaders may try to do otherwise, the demographic realities of population ageing and increased human longevity cannot be truthfully denied, politically finessed or legislated away. Eventually, the demographic piper will be paid, one way or another.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, IPS – Inter Press Service.

Joseph Chamie is an independent consulting demographer and a former director of the United Nations Population Division.