Last summer, I hosted a hackathon for middle school students at Medgar Evers College. Picture 40 enthusiastic young people ready to learn about coding, computer science, and technology, along with CodeEd educators and the welcoming college staff.

In an effort to be as educational as possible, I like to do a little history quiz when we host young people. My quiz features questions like, “Who was the first African-American woman elected to Congress?” That day, I asked, “Who was Medgar Evers?” Silence. The question stumped nearly all the students.

Only one student could venture a reply on his Civil Rights Movement leadership. That lone reply is part of the reason I am advancing legislation to make black history instruction in our K-12 schools mandatory.

The Southern Poverty Law Center recently published a troubling report on schools teaching the history of slavery, “Teaching Hard History.” Among the most alarming findings, SPLC reports that two-thirds of high school seniors did not know it took a constitutional amendment to end slavery; 58 percent of teachers found their textbooks inadequate in teaching about slavery; the average textbook scored only 46 percent in SPLC’s assessment of what should be included in the study of American slavery; 40 percent of teachers believed their state offers insufficient support for teaching about slavery.

The SPLC’s analysis provides important data supporting the need to make black history instruction mandatory, mirroring my experience with the hackathon students and elsewhere.

Recent news reports underscore the necessity of this legislation. In one Bronx school, I.S. 224, the principal reportedly instructed an English teacher not to teach about the Harlem Renaissance. In another school, administrators refused to allow a student named Malcolm Xavier Combs to put “Malcolm X” on his senior sweater. In another instance, in Park Slope, the PTA included images of performers in blackface on advertisements for a 1920s themed fundraiser. Passing this law would send a clearly needed message of inclusion to all New Yorkers.

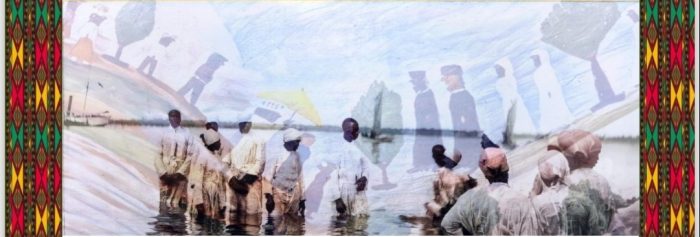

Black history’s importance extends far beyond a single month. From the abolitionists like Sojourner Truth, who broke barriers in advocacy and helped end slavery, to the Harlem Renaissance, home to literary and artistic dynamism we benefit from even today, to the pioneering achievements of Shirley Chisholm, who paved a path for future public servants of color, men and women alike, black history serves as part of our national heritage.

Our young people should engage with black history in thoughtful, age-appropriate ways, throughout their time as students. Black history provides a panoply of avenues across subject areas for K-12 students to explore, intersecting with social studies, English language arts, performing and visual arts, and more. I have every confidence that the Board of Regents and educators across various disciplines can successfully weave the richness of black history and New York’s unique place in black history into school curricula.

A crossroads for the world, New York’s Black History intersects with experiences of the Afro-Caribbean community, the Afro-Latino community, and the entire African diaspora. Under the provisions of my black history in schools proposal, the Board of Regents would be responsible for determining how Black History is best incorporated into students’ studies.

Sociologists point to the black experience being underrepresented overall in media, missing stories altogether, exaggeration of negative portrayals, and providing positive portrayals within only a narrow scope. These broader facts have consequences for young peoples’ development, self-esteem, expectations, and what figures are even available as role models. Requiring black history in schools is not a silver bullet, but it marks an important further development in chipping away at stultifying boundaries to opportunities.

I invite the public to join in support of an holistic effort to think about black history and participate in embracing a curriculum recognizing New York’s unique place in black history. New York is blessed with a rich variety of institutions that can contribute to making this inclusive move a success, the Weeksville Heritage Center in Brooklyn, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, and all our museums, libraries, and numerous institutions of higher education can make valuable contributions to this effort.

This broader integration of black history into our schools is as important to our future as the coding and computer science those middle school students learned at Medgar Evers College. Such a curriculum leaves the boundaries of the schoolhouse and will help bolster New York students’ college- and career-readiness, engaging them, sharpening their skills, and preparing them for the diverse and dynamic communities they will lead their lives in.

Jesse Hamilton is a state senator representing Brooklyn’s 20th district. On Twitter @SenatorHamilton.