The four remaining Caribbean Community countries, which are still brave enough to continue producing sugar are demanding political and economic protection from regional governments saying tax free imported sugar from outside the bloc is undermining their efforts to remain in the industry.

The umbrella Sugar Association of the Caribbean (SAC) which met recently in Belize complained to anyone who would listen that up to 70 percent of all sugar consumed in the 15-nation grouping comes “from extra regional sources duty free, displacing market opportunity for more than 200,000 metric tonnes of Caribbean sugar.” Only Guyana, Belize, Jamaica and Barbados are still in the business that dates back to the trans Atlantic slave era. Others like Trinidad and St. Kitts have in the past 15 years dropped out of the sector altogether, saying that their product had become so un-competitive that it no longer made sense to continue operating factories and maintaining estates. It is simply cheaper to import.

In an unusually detailed statement, the sugar cartel contended that governments must act quickly as pressure to sustain daily production is mounting and that “extra regional duty free imports are being dumped into the CARICOM market at less than half the value they achieve in their home markets.” The body wants import tax protection for an indigenously produced product from governments and plans to continue its protracted lobby to persuade governments to slap tariffs on imported sugar.

The SAC did not identify countries which are dumping cheaper sugar into the bloc but has in the past complained about imports from Colombia and Guatemala among others. It said the situation has been worsened by the fact that the European Union has disbanded a preferential scheme for sugar dating back to the European colonial era.

That regime had allowed for fixed quotas and prices and exports for an unlimited duration. The new system, put in place more than 18 months ago, has dealt a major blow to regional exports as bigger players like Australia and Brazil can now sell large amounts to the EU, beating out regional exports.

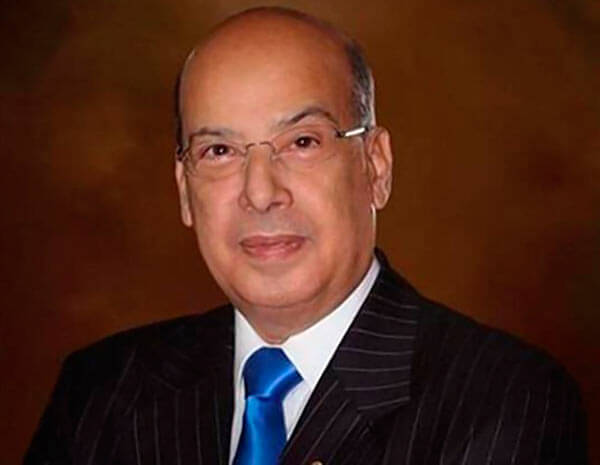

Asked for an update, CARICOM Trade Chief, Joseph Cox said officials dispute the 70 percent figure that the SAC has proferred and suggested that nothing will be done until an accurate picture is garnered about exactly what is happening in the sector. “We can’t verify that figure. We don’t yet know it to be so,” Cox told this publication but stopped short on suggesting what might be the solutions at least in the short term.

The body urged governments to act quickly on policy changes to protect the sector as “a failure to achieve this threatens a major agricultural sector of the region’s economy, hundreds of thousands of Caribbean jobs and questions the effectiveness of the single market (trading system). The four are set to produce a total of 300,000 metric tonnes of sugar in the next 18 months.

Of the four still in the business, Guyana, Jamaica and Barbados are struggling to remain afloat as production costs are sometimes up to three times higher than world prices per pound of sugar. Belize is doing better but, like the others, has to contend with local world market prices and competition from beet sugar of Europe.

Regional sugar has taken several major blows in the past 15 years. Back in 2005 for example, the European Union which had absorbed the largest amount of exports from the region slashed production prices by 36 percent, as part of a process to undermine the special sugar protocol that had been in place for former colonies in Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific, the so-called ACP group of countries.

St. Kitts and Trinidad immediately packed up and started to dismantle their factories while the four remained and negotiated hundreds of millions of dollars in grant aid support from the EU to make up for job losses and general displacement.

A year and a half ago, the EU dismantled the special protocol altogether, opening its once protected doors to any sugar-producing country such as Brazil and Australia, which produce by the millions of metric tonnes annually. This meant that decades of guaranteed prices, fixed quotas and exports for an unlimited duration all went down the drain.

Now the SAC is turning its attention to governments, asking them to tax imported sugar so they could survive what executives say is the last battle on the way to the production cemetery.