“The man of genius inspires us with a boundless confidence in our own powers.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson.

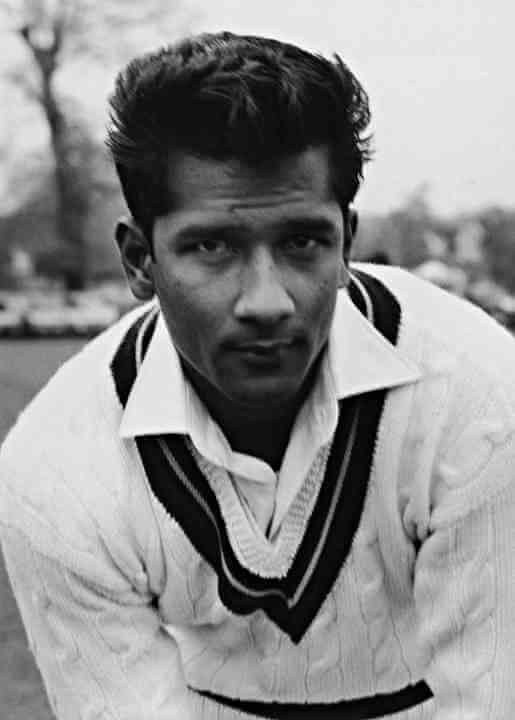

“No more technically correct batsman ever came out of the West Indies than Rohan Kanhai.” — Michael Manley.

“His life was gentle; and the elements so mixed in him, that Nature might stand up, and say to all the world, THIS WAS A MAN!” — William Shakespeare.

“To see Kanhai flat on his back — with the ball among the crowd beyond the square-leg boundary — after making one of his outrageous sweeps to a good length ball, is to watch a man capable of playing shots fit to lay before an audience of emperors” — James Scott, May 1966, on the occasion of Guyana’s Independence

“Kanhai discovered, created a new dimension in batting…He had found his way into regions Bradman never knew.” — CLR James

“Some batsmen play brilliantly sometimes and at ordinary times they go ahead as usual. That one… is different from all of them. On certain days, before he goes into the wicket, he makes up his mind to let them have it. And once he is that way nothing on earth can stop him. Some of his colleagues in the pavilion who have played with him for years have seen strokes that they have never seen before: from him or anybody else” — Sir Learie Constantine to CLR James, on Kanhai.

“I remember my first sight of Rohan Kanhai batting at Bourda in 1956. I wrote that night to my father in Trinidad that I had just been witness to a wonder, the best batsman in the world. This was a big claim — after all I had seen, among others, the great Frank Worrell at his elegant best. But I was sure then and I was sure thereafter as I followed Kanhai’s career…of all the sportsmen in all the many sports I have watched in my life I judge Kanhai to have possessed the most compelling genius of them all…It was, quite simply, a special gift from the gods.” — Ian McDonald.

“Rohan Kanhai was a great player…and he was rated one of the tops…a good cricket brain…earned the respect of his players.” — Sir Garfield Sobers.

“His niche in West Indies cricket…is assured, as is his place in the hearts of all who treasure human excellence in any form.” — Michael Gibbes.

“It is hard to believe that there could be better players than Rohan Kanhai. I have seen him score tons for Warwickshire on all sorts of pitches — against Derek Underwood on turning tracks and against Alan Ward and Harold Rhodes on a corrugated flyer against Derbyshire. Rohan got hundreds on both occasions. Nobody can be a fine cricketer than Garfield Sobers or Ian Botham but somehow Kanhai hardly gets a mention. I stood at the other end many times completely in awe of him” — Dennis Amiss on his former Warwickshire teammate, Rohan Kanhai.

To understand what cricket supremacy means in a global context to the average Caribbean man is best summarized by the former Prime Minister of Jamaica, Michael Manley: “The West Indies are Third World countries, but we belong and are in the First World of Cricket.” Cricket is not only a religion in the Caribbean, but it best defines the region in any context. Regional political integration has followed cricket as a unifying and defining force.

Rohan Kanhai, one of my boyhood heroes, was undoubtedly the most extraordinary batsman the West Indies has ever produced, blessed with such natural abilities that he could eviscerate any bowling attack in the world when he controlled the impetuosities that raged within him. There was beauty in his craft, so much different in his method of annihilation, especially on the treacherous uncovered wickets in his days. Whereas other batsmen could wear down an attack, Kanhai would dissect it with clinical precision. He was poetry, rather than prose. Ballet, rather than dance. Artistry, rather than sheer power, although this never compromised the force with which he hit the ball. He glided in riveting stroke play, batting with the dexterity of a virtuoso, yet prone to Shakespearian tragedy at any time. Kanhai on the rampage was a mesmeric joy to behold, even for bowlers.

He did not have the superlative statistics nor the sheer all-round cricketing genius of Garfield Sobers, the awesome power of Viv Richards, Clyde Walcott, Clive Lloyd or Gordon Greenidge, the classical poise of Sachin Tendulkar or Frank Worrell, or the steadfastness of George Headley or Steve Waugh.

Nor did he have the impregnable technique or patience of Geoff Boycott, Jack Hobbs or Sunil Gavaskar, the insatiable appetite for runs like Don Bradman, the grace of Greg Chappell or Zaheer Abbas or the oriental calm of Majid Khan. Nor did his interaction with the game of cricket spawn changes to the socio-political structures of society and effect reforms of a radical nature as Learie Constantine’s and W.G. Grace’s did.

Nor did he assume superstar status like Brian Lara or Sachin Tendulkar. Nor did he achieve batting statistics to propel him to the type of immortality attained by Sir Don Bradman, Lara or Tendulkar. Yet, Kanhai possessed a combination of batting prowess, originality and sportsmanship above and beyond the reach of all of these great players to such an unparalleled degree that has never been seen in the game of cricket and perhaps will never be equaled. His arrival to the wicket heralded both hush and expectancy. Bars closed as all looked to the drama that was about to unfold before a Kanhai innings.

His creative genius surpassed any other batsman in the game, and his flamboyance was spellbinding. There were times in his batting artistry where he touched heights of batsmanship beyond the reach of any batsman, such as in the execution of his unique “triumphant fall, roti shot,” or falling hook shot, most times played off the eyebrows, the half-pull, half-sweep style stroke, the flick off the toes which dissected the on-side field, the reverse sweep off the leg stump, the magical late-cut or his majestic cover driving.

Cricketers like him invented and pioneered many innovations to the game which have made it richer and dearer to spectators. As cricket scribes would say, “Many batsmen may enter the same cathedral of batsmanship with Kanhai, but will not be allowed to sit in the same pew.” In Michael Manley’s book, “A History of West Indian cricket,” Kanhai is photographed sitting with George Headley and Everton Weekes, and that is how they may all sit in the front pew of that proverbial cathedral, with Viv Richards, Brian Lara, Gary Sobers and Frank Worrell.

In his book “Idols,” Sunil Gavaskar, whose gigantic batting feats have not only eulogized him in calypso but also immortalized him in a manner second to none, said this of Kanhai: “Rohan Kanhai is quite simply the greatest batsman I have ever seen. What does one write about one’s hero, one’s idol, one for whom there is so much admiration? To say that he is the greatest batsman I have ever seen so far is to put it mildly. A controversial statement perhaps, considering that there have been so many outstanding batsmen, and some great batsmen that I have played with and against. But, having seen them all, there is no doubt in my mind that Rohan Kanhai was quite simply the best of them all.”

Gavaskar continues, “Sir Gary Sobers came quite close to being the best batsman, but he was the greatest cricketer ever, and could do just about anything. But as a batsman, I thought Rohan Kanhai was just a little bit better.” In his book “Living For Cricket,” Clive Lloyd definitively said that he regarded Kanhai as “the finest batsman Guyana has produced.” In his book, “Willow Patterns,” Richie Benaud, one of the most respected cricket gurus, confirmed that he “thought that Kanhai was just a shade over Sobers.”

Kanhai’s greatness lies to a great degree with his connection to history, and the way he overcame the social and political forces of British imperialism, which subdued him in his time. A captivating player, he carried the hopes and aspirations of the Caribbean people during a period of political deprivation in their collective history, where his sweet successes or bitter failures mirrored theirs in the shackles of colonialism.

They celebrated when Kanhai shone, brooded when he failed. In my boyhood days, he inspired youngsters like myself that, like him, we too could one day reach international fame. With his showmanship and range of breathtaking strokes, few batsmen will ever attain the idolatry of Kanhai. He was a born favorite. Although one never to chase after batting records, Kanhai nevertheless achieved an impressive array of memorable milestones.

For example, although Tendulkar is the modern icon of batsmanship, he has never scored a test century in each innings of a test match as Kanhai did against as worthy an opponent as Australia, at Adelaide in 1960-61, nor top the batting averages in an English season as he did in 1975 with an average of 82.53, nor share in such high wicket partnerships in First Class cricket as he did with J.A. Jameson-465*, Warwickshire v. Gloucestershire, 1974, second wicket and with K. Ibadulla-402, Warwickshire v. Notts, 1968, fourth wicket.

And who would not help but admire his one day average of 55 runs per innings? Or, notwithstanding the fact that statistics were always the furthest thing from his mind, appreciate that he scored 83 first class centuries, and countless 90’s, each innings a spectator’s dream?

Rohan opened the doors for others to follow. Perhaps “opened” is a mild word. Kanhai blasted the door open for other West Indians to follow. After all, his book was aptly entitled, “Blasting for Runs.” In fact, Gavaskar, Kallicharran and Bob Marley named their sons after Rohan Kanhai, and many West Indians all over the Caribbean are named after him, a testimony to Kanhai’s greatness. Gavaskar also hoped that his son Rohan would be at least half as good as the original Rohan Babulal Kanhai, which he said would make him very proud indeed! We will never see his like again…Remember the man!