“The heights by great men reached and kept were not attained by sudden flight, but they, while their companions slept, were toiling upward in the night.”

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

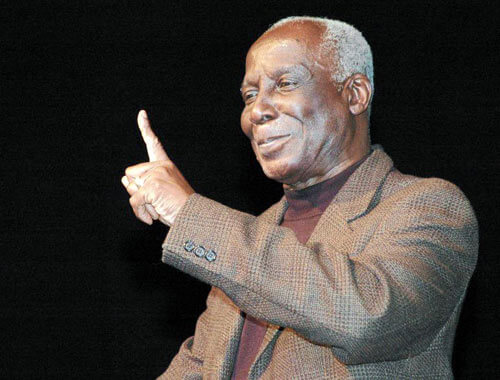

One month after the island declared independence from Britain, Rex Nettleford launched a national, performing, arts group he named The National Dance Theater Company of Jamaica.

It was no accident that the same year Jamaica freed itself from colonial bondage nationals also danced to a new rhythm.

Perhaps driven by a desire to exercise creative freedom, Nettleford and his colleague Eddy Thomas birthed the entity that some might consider a manifestation declaring “out with the queen, in with the king.”

Dubbed “King of Kumina” Nettleford was nicknamed Rex longer than many can recall.

Dance enthusiasts revered him for glorifying “Kumina and Pocomania,” – revivalist religious ritual which beckons African ancestral spirits using drums during traditional ceremonies.

While Quadrille exalted Europeans in dance, Kumina illuminated the African tradition.

Born in rural Jamaica, on Feb. 3, 1933, Ralston Milton Nettleford spent his early years in Bunkers Hill, Trelawny in the parish of Falmouth.

The boy nicknamed the Latin word for king showed early signs of genius and perhaps an ambition akin to royalty.

The teenaged youth studied at Cornwall College then furthered his education at Kingston’s University College of the West Indies focusing on history. After attaining a bachelor’s degree there, in 1957, he earned a Rhodes scholarship to study political science at Oxford University.

After graduation, he returned home and seized every opportunity to aid in the growth of his country.

“The power to create and innovate remains the greatest guarantee of respect and recognition,” Nettleford said.

“The jailers and the jailed are after all both in jail.”

His voice emerged one to listen and learn from.

The entire Caribbean listened when he verbalized his hope for the region.

His dream was for development of a “sense of self worth, that self esteem which bolsters confidence in self to further forge in the crucible of a heritage a viable plural society where people live not just side by side, but together.”

In his first book, he focused on self esteem and identity.

“One unifying force in the Caribbean heritage is undoubtedly the African Presence. We may as well admit to ourselves the great moral strength that would accrue to Caribbean civilization were we to eschew once and for all the lingering plantation and colonial assumptions about the natural inferiority of those of its inhabitants who carry the ‘stain’ of Africa in their blood.”

Published, 1970, “Mirror, Mirror – Identity, Race & Protest in Jamaica,” he examined racial and social issues in Jamaica.

His essays on “The Rastafari Movement in Kingston,” and “Manley & The New Jamaica” distinguished an important intellectual contributor.

Nettleford wrote and edited speeches for founding father and Premier Norman Washington Manley.

In an effort to narrow the divide he identified between Jamaicans of African descent and others he said:

“The hidden history of Jamaica is here seen as the history of the struggle of the African component to emerge from the subterranean caverns into which it has been forced.”

He was named vice chancellor of the University of the West Indies and in 1975 the nation honored him with the Order of Merit, the third highest distinguished award.

In 2008, Nettleford was awarded the Caribbean region’s highest honor, the Order of the Caribbean Community (OCC) for his years of dedicated service as a regional ambassador. This award cemented Nettleford as the quintessential Caribbean citizen and international cultural icon.

The intellectual was a frequent visitor to Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Culture for Research in Black Culture.

His colleague, Howard Dodson, former curator of the world’s largest archive on Black culture often invited Nettleford to join forums at the landmark location. In 2007, when the African Burial Ground opened to visitors, Nettleford joined Dodson and other significant guests to dedicate the lower Manhattan national monument.

Nettleford’s mother died at age 100, in the Bronx in 2009.

She had seen him dance, choreograph and champion his people.

After her passing he wrote to Prime Minister PJ Paterson saying:

“Jamaican mothers are in a class by themselves. She retained her protective responsibility throughout her life from as far back as I can remember. She was not afraid to accost the Horsehead in a Jonkonnu band for frightening her three year old son…

This writer was privileged to see and hear Nettleford at the UWI when he welcomed Nelson Mandela

to the island in 1991.

I can recall the admiration and pride on the faces of students who seemed entranced by every word he uttered in introducing the South African freedom fighter.

I also witnessed how he pranced and danced to drums, from Town Hall to Brooklyn.

Watching him strut the stage to receive standing ovations for his royal performance of “Kumina” at Brooklyn College was always beguiling.

He managed to unite Caribbean nationals to this annual showcase.

The same passion exuded when he spoke eloquently about African heritage, Jamaica and the Caribbean.

Feb. 2, 2010, Nettleford died of a heart attack one day before his 77th birthday.

In addition to 14 honorary degrees and doctorates from universities around the world, Nettleford also served on the executive board of UNESCO, and the World Bank.

Jamaica Information Service lists his credits:

•Student of the Year, University College of the West Indies, 1954/55

•Issa Scholarship, and Rhodes Scholarship for Jamaica, 1957

•International Labor Organization Fellowship (Labor Education), 1967

•Associate Fellow, Centre for African and Afro-American Studies, University of Atlanta, 1970

•Founding Governor, International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Canada, 1970

•JAYCEES of Jamaica Outstanding Young Jamaican Award, 1972

•Order of Merit (OM), 1975

•Thelma Hill Dance Award, New York, for dance, ’Men In Black’, 1981

•Institute of Jamaica’s Gold Musgrave Medal Award for 1981 in the field of Arts (Dance), 1981

•Award of Honor, Joint Trade Union Research Development Centre of Jamaica, 1983

•Fellow, Institute of Jamaica (FIJ), 1989

•Living Legend Award from the Black Arts Festival, Atlanta, Georgia, 1990

•Pelican Award from the Guild of Graduates of the University of the West Indies (UWI), Mona, Jamaica, 1990

•Kingston and St. Andrew Corporation Award in the field of Culture and Arts for outstanding contribution to the advancement of Public Welfare, 1992

•Marcus Garvey Award from the Jamaica National Movement New York Inc, 1993

•Zora Neale Hurston/Paul Robeson Award from the national Council for Black Studies Inc., USA, 1994

•Sir Shridath Rampaul Award for Cultural Posterity presented by Irvine Hall at Culturama 1995, UWI, Mona, 1995

•Trinidad and Tobago folk Arts Institute’s Citation, 1995

•Caribbean Writers Award, Carifesta VI, Trinidad and Tobago, 1995

•Order of the Caribbean Community (OCC), 2008

•Chancellor’s Medal of the University of the West Indies, 2009