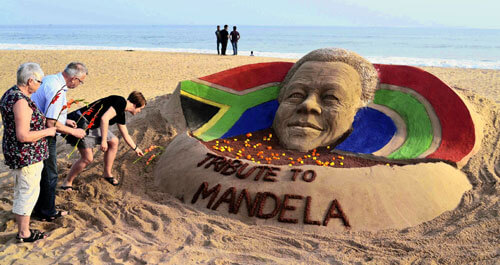

Those of us who worked for the Black press in 1990 will not soon forget the visit of Nelson and Winnie Mandela to New York City four months after the freedom-fighter’s release from a 27-year confinement in the brutal South African prisons.

Here for the first three days of a twelve-day, eight-city, campaign to keep economic and political pressure on the government of South Africa to end apartheid and accept majority rule, leader of the African National Congress found New Yorkers waiting to shout “Amandla!” and “Keep the Pressure On.”

Slated to visit Boston, Washington D. C., Atlanta, Detroit, Los Angeles, Oakland and New York, this one was the one that mattered most to many of us working in the media capital of the world.

The pre-blog, pre-internet era demanded full, national attention to duty and members of the Black press considered regarded the opportunity one to deliver a focus few could duplicate in traditional media. With WLIB-AM the designated electronic media fully dedicated to provide coverage of the arrival of the iconic figures, reporter Dominic Carter pooled report from touchdown. Providing print coverage to colleagues, I was the pooled reporter to transmit coverage from Boys & Girls High School where the newly-released from prison, freedom-fighter stopped to greet youths.

Newsday reporter Merle English stood next to me as the couple beamed gratitude and love to the thousands gathered in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

While that gathering was significant, the Mandela’s welcome through the Canyon of Heroes brought teary-eyed New Yorkers to the fore.

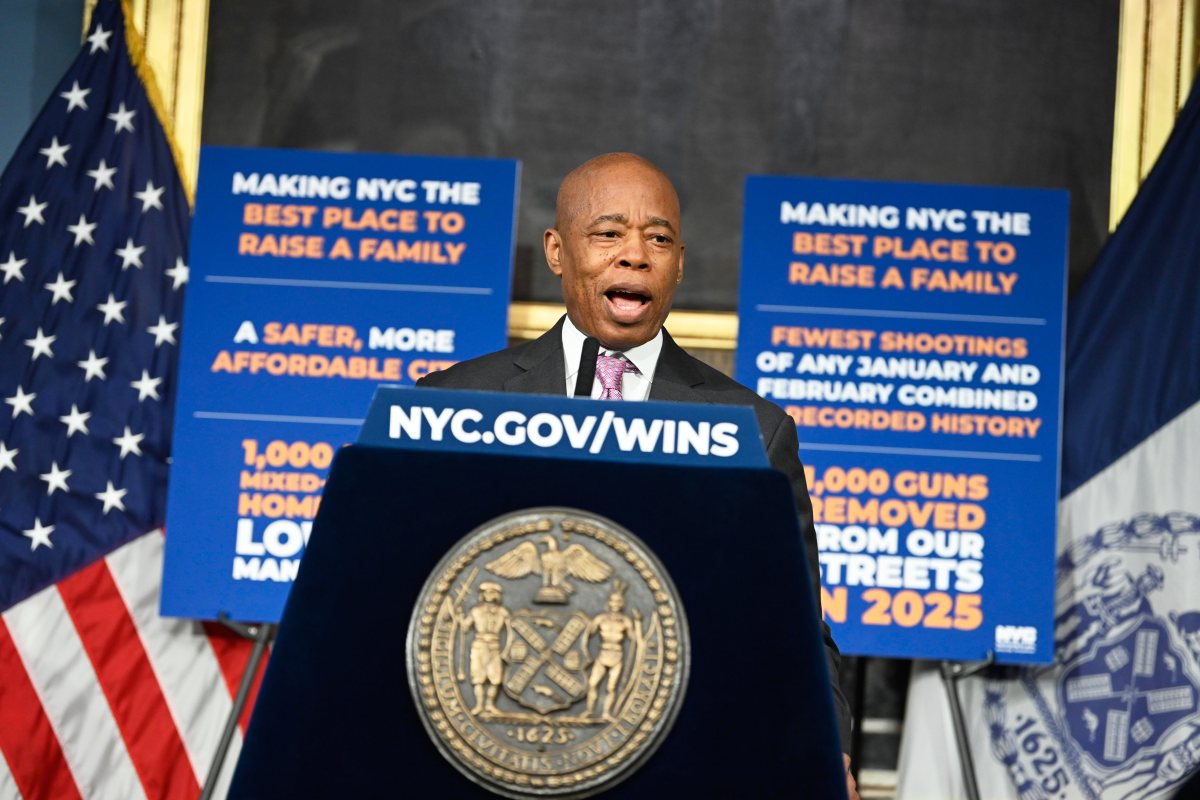

The city’s first Black Mayor David N. Dinkins looked accomplished greeting his most significant guests to City Hall. Some of the details are a blur, however, crystal clear to me was the next stop that same day uptown to Harlem where at the intersection of Martin Luther King and Adam Clayton Powell Blvds., a stage was erected to accommodate the guest of honor and other dignitaries.

Activist Elombe Brath and his Patrice Lumumba Coalition had demanded the stop into the renowned Village.

As many dignitaries jostled for a place alongside the Mandelas, Betty Shabazz, the widow of Malcolm X stood as if directed and without purposeful showboat. I will never forget Winnie’s reaction when she was told that the woman next to her was the wife of Malcolm X. As if she was hit by a lightning bolt, the South African warrior grabbed Shabazz, caressed her and whispered what seemed a glowing acknowledgement and gratitude of the role she contributed to American history.

Winnie glowed with pride, looked out into the crowd of approximately 200,000 and described her view from what she termed the “Soweto of America.”

Next it was onto Yankee Stadium where the rest of NYC gathered to cheer the international figures.

The subway proved the best mode of transportation to get to the Bronx.

Harry Belafonte was the first celebrity I recalled seeing at the site.

Legions more appeared.

Artists United Against Apartheid – a consortium of entertainers who protested going to SA until apartheid ended – and names that come to mind includes singers Judy Collins, Richie Havens, Tracy Chapman, calypso legend the Mighty Sparrow and others.

But there was no one as celebrated as Nelson Mandela who wore a blue and white Yankee baseball cap and jacket.

He was more than a celebrity, he was a hero.

“I Am a Yankee!” Mandela declared.

I can still hear the cheers of appreciation for those words.

They were more for the man than the comment.

Early the next morning, Mandela jogged past many of us positioned outside Gracie Mansion where he stayed with the Dinkins’ house-hold.

I was up in the balcony at Rev. Herbert Daughtry’s House of the Lord Pentecostal Church in Brooklyn when Winnie returned to the borough.

From the Atlantic Avenue activist church, she rushed afterwards to face another throng of supporters who congregated at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Female, reporters representing the Black press dominated the media pool.

At another venue, Spike Lee hosted a fund-raising benefit for the ANC her husband attended.

One year later, I was privileged to join the press corps when the couple visited Jamaica.

Outside the Wyndham Hotel in Kingston, thousands waited to join a procession to the Mona campus and location of the University of the West Indies where Madiba would be conferred with an honorary degree.

On a day Stevie Wonder might consider ‘hotter than July,’ invited guests packed into a non-air-conditioned space at UWI. Draped in the robe of the college, the 73-year-old broker of peace in South Africa emerged alongside Rex Nettleford and other intellectuals.

I recall fanning incessantly for air to sustain me. I also remember worrying that the long introductions and the almost unbearable heat might cause the frequent traveler to faint. And although Mandela was draped in extra fabric he endured and was able to accept accolades from Sir Shridath Ramphal who conferred the honorary Doctor of Laws.

A rally at the Jamaica’s National Stadium enabled public access to the hero. There artists such as Third World, Carleen Davis and others delighted the visitor. I sat in the Grand Stand next to poet Mutabaruka and together we shared notes and reflections.

Three years later I went to South Africa with dancehall artist Shabba Ranks.

Numerous volunteers from the USA campaigned and urged voter participation.

Peter Noel, a Trinidad & Tobago colleague who worked for the Village Voice had been selected as the newspaper’s correspondent to cover the campaign.

On arrival, it was evident history was in the making.

The black, gold and green colors of the ANC formed buntings throughout Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban.

Those are also the colors of Jamaica’s flag.

In 1994, Ranks was the ranking Jamaican, dancehall entertainer.

Arriving on the March 21, 1960 anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre Ranks he dressed to impress in his national colors.

Mandela wore the same colors for a different reason.

However, when they stood side-by-side in front of a crowd that seemed like millions, it was evident that Mandela was destined for more greatness.

South Africa held its first democratic elections that same year. On the ballot, the incumbent National Party’s F.W. de Klerk, Mangosuthu Buthelezi of the Inkatha Freedom Party and Mandela of the African National Congress allowed choice for the first time.

On May 2, 1994, de Klerk conceded defeat.

He delivered a gracious speech saying Mandela had “walked a long road and now stands at the top of the hill.” He added that “A traveler would sit down and enjoy the view but a man of destiny knows that beyond this hill lies another and another… As he contemplates the future I hold out my hand in friendship and cooperation.”

I was privileged to see and hear the international hero address the General Assembly at the United Nations.

A footnote and highpoint for Jamaica was when Jamaica and South Africa established diplomatic relations.

It was on Sept. 9, 1994.

Give thanks. Nelson Mandella died with dignity.

I will always remember Madiba, my hero.