UNITED NATIONS, April 19, 2019 (IPS) — Journalists around the world are increasingly seeing threats of violence, detention, and even death simply for doing their job, a new press index found.

In the 2019 World Press Freedom Index, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) has found a worrisome decline in media freedoms as toxic anti-press rhetoric have devolved into violence, triggering a climate of fear.

“The scene this year is fear. And the state of journalism and press freedom around the world is declining… but also in the traditional press freedom allies — countries in Europe and here in the United States,” said RSF’s Executive Director, Sabine Dolan during the launch of the index.

RSF Secretary-General Christophe Deloire echoed similar sentiments about the dangers of declining press freedom, stating: “If the political debate slides surreptitiously or openly towards a civil war-style atmosphere, in which journalists are treated as scapegoats, then democracy is in great danger…Halting this cycle of fear and intimidation is a matter of the utmost urgency for all people of good will who value the freedoms acquired in the course of history.”

Of 180 countries evaluated in RSF’s index, only 24 percent were classified as “good” or “fairly good” compared to 26 percent in 2018.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region continues to be the most dangerous area for journalists as they face violence due to ongoing conflicts while also being deliberately targeted, imprisoned, and killed.

For example, Emirati blogger Ahmed Mansoor was sentenced to 10 years in prison after criticising the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) government on social media.

He was accused of “publishing false information, rumours and lies” which would “damage the UAE’s social harmony and unity.”

The persecution of MENA’s journalists has even extended past its own borders as seen through the brutal murder of Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi Consulate in Turkey.

Such a chilling level of violence has provoked fear among the region’s journalists, causing many to censor themselves.

But of all the world’s regions, it is the Americas that has seen the largest dip in its press freedom score.

Nicaragua for instance fell 24 places to 114th, making it one of the steepest declines worldwide — and with good reason.

What started as protests against controversial social security reforms has turned into one of the biggest crackdowns on dissent and media in the Central American nation.

Nicaraguans covering demonstrations have been treated as protestors or members of the opposition and have been subject to harassment, arbitrary arrest, and death threats.

Some have been charged with terrorism including Miguel Mora and Lucia Pineda Ubau, journalists for the news agency 100% Noticias.

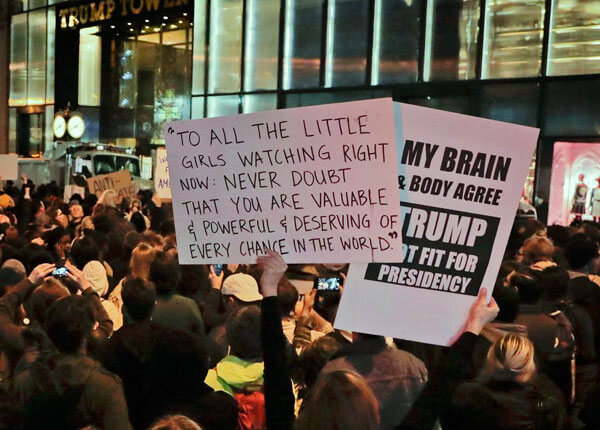

Further north, the United States’ media climate is now classified as “problematic” as a result of an increasingly toxic anti-media rhetoric.

Over the last year, media organisations across the country received bomb threats and suspicious packages including CNN, forcing evacuations.

In June 2018, after expressing his hatred for the Capital Gazette newspaper on social media, Jarrod Ramos walked into the newsroom and killed four journalists and a staff member.

Most recently, Coast Guard lieutenant Christopher Paul Hasson was arrested for planning a terrorist attack targeting journalists and politicians.

Such anti-media sentiment is partially fuelled by U.S. President Donald Trump who has called journalists “enemy of the people.”

“When this becomes constant, it’s almost normalised and it percolates to large segments of the population. And this is how it has contributed to create this climate of fear for journalists,” Dolan said.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), over 11 percent of the president’s tweets have insulted or criticised journalists and news media.

In reference to a particular tweet by Trump which states that it is “disgusting” that the press can write whatever they want, former White House Correspondent Bill Plante noted that the U.S. is in a very “dangerous place” now.

“It is one thing to steer news coverage, by putting things out there or leaking certain stories or trying to avoid coverage of other things — it’s entirely another to threaten reporters and to say that news coverage shouldn’t be allowed,” he said.

This rhetoric has not only impacted journalists in the U.S., but has also spilled over abroad as world leaders from Venezuela to the Philippines use terms like “fake news” to justify human rights violations and crackdowns on press freedom.

But it is not all bad news.

Ethiopia made an unprecedented 40-place jump in the Index after new Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed took swift steps to improve press freedom including the release of all detained journalists.

While such progress is promising, there is a long way to go to secure press freedom globally, especially as it seemingly regresses.

“The only weapon we have is truth. The problem is that in today’s media environment along with social media, we can be overwhelmed. So we have to come out there with more effort than ever to get the truth out,” Plante said.