MORANT BAY, Jamaica, Nov. 24, 2014 (IPS) – As Jamaica struggles under the burden of an ongoing drought, experts say ensuring food security for the most vulnerable groups in society is becoming one of the leading challenges posed by climate change.

“The disparity between the very rich and the very poor in Jamaica means that persons living in poverty, persons living below the poverty line, women heading households with large numbers of children and the elderly are greatly disadvantaged during this period,” Judith Wedderburn, Jamaica project director at the non-profit German political foundation Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES), told IPS.

“The concern is that as the climate change implications are extended for several years that these kinds of situations are going to become more and more extreme, [such as] greater floods with periods of extreme drought.”

Wedderburn, who spoke with IPS on the sidelines of a FES and Panos Caribbean workshop for journalists held here earlier this month, said Caribbean countries – which already have to grapple with a finite amount of space for food production – now have the added challenges of extreme rainfall events or droughts due to climate change.

“In Jamaica, we’ve had several months of drought, which affected the most important food production parishes in the country,” she said, adding that the problem does not end when the drought breaks.

“We are then affected by extremes of rainfall which results in flooding. The farming communities lose their crops during droughts [and] families associated with those farmers are affected. The food production line gets disrupted and the cost of food goes up, so already large numbers of families living in poverty have even greater difficulty in accessing locally grown food at reasonable prices and that contributes to substantial food insecurity – meaning people cannot easily access the food that they need to keep their families well fed.”

One local researcher predicts that things are likely to get even worse. Dale Rankine, a PhD candidate at the University of the West Indies (UWI), told IPS that climate change modelling suggests that the region will be drier heading towards the middle to the end of the century.

“We are seeing projections that suggest that we could have up to 40 percent decrease in rainfall, particularly in our summer months. This normally coincides with when we have our major rainfall season,” Rankine said.

“This is particularly important because it is going to impact most significantly on food security. We are also seeing suggestions that we could have increasing frequency of droughts and floods, and this high variability is almost certainly going to impact negatively on crop yields.”

He pointed to “an interesting pattern” of increased rainfall over the central regions, but only on the outer extremities, while in the west and east there has been a reduction in rainfall.

“This is quite interesting because the locations that are most important for food security, particularly the parishes of St. Elizabeth [and] Manchester, for example, are seeing on average reduced rainfall and so that has implications for how productive our production areas are going to be,” Rankine said.

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced recently that September 2014 was the hottest in 135 years of record keeping. It noted that during September, the globe averaged 60.3 degrees Fahrenheit (15.72 degrees Celsius), which was the fourth monthly record set this year, along with May, June and August.

According to NOAA’s National Climatic Data Centre, the first nine months of 2014 had a global average temperature of 58.72 degrees (14.78 degrees Celsius), tying with 1998 for the warmest first nine months on record.

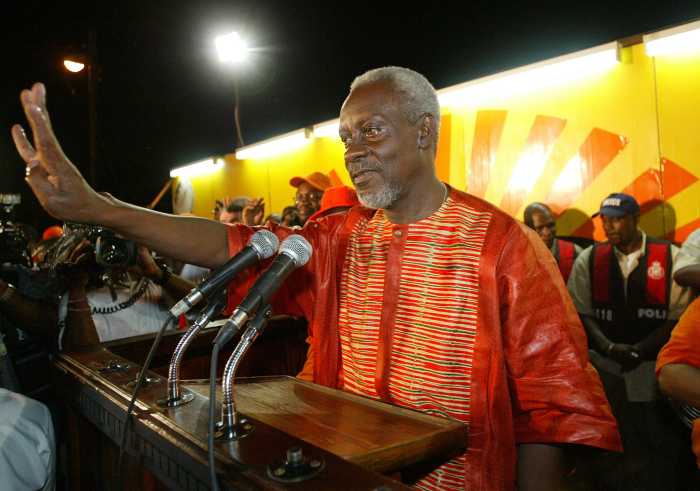

Robert Pickersgill, Jamaica’s water, land, environment and climate change minister, said more than 18,000 small farmers have been affected by the extreme drought that has been plaguing the country for months.

He said the agricultural sector has lost nearly one billion dollars as a result of drought and brush fires caused by extreme heat waves.

Pickersgill said reduced rainfall had significantly limited the inflows from springs and rivers into several of the country’s facilities.

“Preliminary rainfall figures for the month of June indicate that Jamaica received only 30 per cent of its normal rainfall and all parishes, with the exception of sections of Westmoreland (54 percent), were in receipt of less than half of their normal rainfall. The southern parishes of St Elizabeth, Manchester, Clarendon, St Catherine, Kingston and St. Andrew and St. Thomas along with St Mary and Portland were hardest hit,” Pickersgill said.

Clarendon, he said, received only two percent of its normal rainfall, followed by Manchester with four percent, St. Thomas six percent, St. Mary eight percent, and 12 percent for Kingston and St. Andrew.

Additionally, Pickersgill said that inflows into the Mona Reservoir from the Yallahs and Negro Rivers are now at 4.8 million gallons per day, which is among the lowest since the construction of the Yallahs pipeline in 1986, while inflows into the Hermitage Dam are currently at six million gallons per day, down from more than 18 million gallons per day during the wet season.

“It is clear to me that the scientific evidence that climate change is a clear and present danger is now even stronger. As such, the need for us to mitigate and adapt to its impacts is even greater, and that is why I often say, with climate change, we must change,” Pickersgill told IPS. Wedderburn said Jamaica must take immediate steps to adapt to climate change.

“So the challenge for the government is to explore what kinds of adaptation methods can be used to teach farmers how to do more successful water harvesting so that in periods of severe drought their crops can still grow so that they can have food to sell to families at reasonable prices to deal with the food insecurity.”

Edited by Kitty Stapp

The writer can be contacted at destinydlb@gmail.com