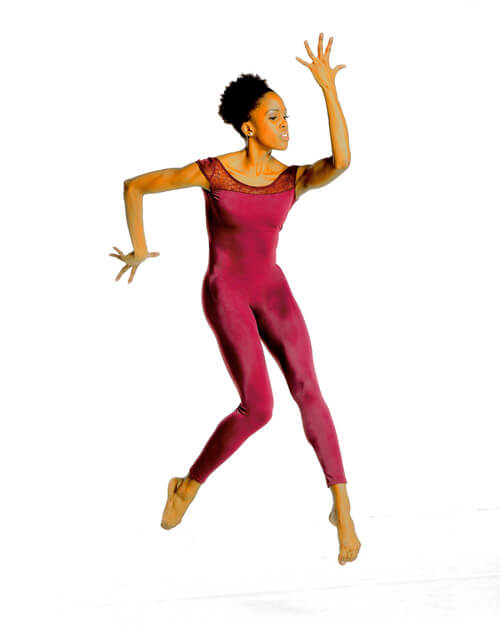

The National Black Touring Circuit featured Kim Brockington as Zora Neale Hurston, in a one-woman play written by Laurence Holder, and directed by Wynn Handman, as part of the Black History Month Play Festival, which runs through Feb. 26.

During the festival shows such as “The Good Fight: A Phillip Randolph” starring Ralph McCain, was held Feb. 3-5; Zora Neale Hurston ran Feb. 10 through 12; “Adam” is running at the Dwyer Cultural Center, at 258 St. Nicholas Avenue in Manhattan, Feb. 17-19, starring Timothy Simonson, and “I, Barbara Jordan” starring Toni Seawright, finishes the series at the National Black Theatre, located at 2031 Fifth Avenue, on Feb. 24-26.

“I wouldn’t be doing Zora if it weren’t for Woodie King, Jr., and Elizabeth Van Dkye. Initially Elizabeth was portraying Zora with Joseph Edwards. The show was top shelf. I caught her show and was very impressed. A year later, Woodie called me to say Elizabeth could not do the show in Bethlehem, PA and asked whether I could I go on in her place. I did not have to do anything but say ‘yes.’ And I did. Elizabeth was generous and gave me the blocking. Woodie gave me the script and I had six weeks to get ready for it. I had some pretty big shoes to fill. I started playing the role whenever Elizabeth could not do a performance,” said Kim Brockington.

“I have always been interested in the life of Zora Neale Hurston. Born in Notasulga, Alabama in 1891, Zora was the fifth of eight children. Zora was a fun loving, outrageous, bodacious individual who was all about getting her art out to the world. She became the literary queen of the Harlem Renaissance. “Her Eyes Were Watching God was one of her most famous books,” stated Kim who loves portraying the role.

Ms. Brockington portrayed Zora in a PBS documentary. “I talk about Zora’s childhood in the PBS version,” remarked the talented performer. “Zora’s mother died when Zora was young and it changed Zora’s whole world. Her father married very soon afterward. Zora’s father was a ladies man and always a bit scandalous. His new wife did not like Zora, so Zora was sent her off to school. Eventually, her father stopped paying for school and she was kicked out. She got a job in a traveling theatrical show as a maid. Zora always loved storytelling, thus it’s no surprise she became a writer. She returned to school attending Morgan where she finished high school. By the time she got to Howard University, she was writing. She was 28. She went on to Barnard where she majored in anthropology.”

Ahead of her time, Zora was a poet, writer and anthropologist, who won several awards and contests. Eventually she won a Guggenheim Fellowship allowing her to travel to Jamaica and Haiti, where she studied African voodoo rituals. Hurston continued her research in America’s southland where she collected and wrote about African American folklore.

During the Harlem Renaissance era, a lot of the artists had patrons who sponsored their work. Charlotte Mason was Zora’s patron. Ms. Mason was an influential woman who gave Zora money for clothes, books and lodging. Langston Hughes also had a patron but criticized Zora for allowing her patronage to go on too long. Charlotte Mason, who insisted Zora called her “Godmother,” was very controlling and wanted to control Zora’s art, forcing Zora to acquiesce to Charlotte demands. Zora felt smothered, frustrated and angry under Godmother’s control. Finally, she got away from Godmother after publishing Jonah’s Gourd Vine in 1934. “Moses, Man of the Mountain” was published in 1939. Ms. Hurston’s periodicals were published in The Saturday Evening Post, and American Mercury.

She contributed to “Woman in the Suwannee County Jail,” a book written by journalist William Bradford Hule. As a folklorist, Hurston oftentimes wrote in the dialect of her subject matter, utilizing speech patterns of the period she documented. “Mules and Men,” was another of her works.

Zora studied voodoo in New Orleans and became a voodoo priestess. She established a school of dramatic arts at Bethune College. Then while Zora was in Honduras she was falsely accused of child molestation in the United States. This took a toll on Zora. Even though she was able to prove her innocence the damage had been done. Accusations, primarily detailed in the black press, ruined her life. It became difficult for Zora to find work or get her work published. She took work where she could find it and freelanced for magazines. Broke, tired and disappointed, Zora went home to Alabama where she found work as a maid. She died, buried in an unmarked grave. Alice Walker resurrected Hurston’s work posthumously.

Kim Brockington was born in Baltimore, Maryland. An only child, Kim started performing at five years old. Acting and singing has always been in her blood. She went to Morgan State for a year and transferred to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She has been acting ever since.

She will be performing her one-woman show on Zora at Georgia State University in Atlanta on March 12 for Women’s Month; in May, she is slated to perform Zora in Baltimore and perhaps another performance in New Jersey in June.

Her other credits include an Audelco Award for Outstanding Performance for Archbishop Supreme Tartuffe in 2009. She performed Darlene in “In Walks Ed.” She was nominated for another Audelco Award for “Coming Apart Together.”

In TV and film, Kim appeared in the Spike Lee pilot “Da Brick.” She has appeared in soaps “The Guiding Light,” “One Life to Live,” and “All My Children.” Ms. Brockington guest starred in West Wing, Third Watch, Law and Order Criminal Intent and in films “Rock the Paint,” “School of Rock,” “Love Songs,” and “Dirty Laundry.”

Interested parties can find out more about Kim Brockington via www.kimbrockington.com