The 180-day period for monetary claims by Black farmers against the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) expired on May 11.

When these farmers filed their class-action lawsuit in the mid-1990s (Pigford vs. Glickman), they were but acting on what had been known for decades. Namely, that Blacks had always been systematically discriminated against by the USDA.

The history has been bleak. When Congress created the USDA’s Farmers Home Administration in 1942, it was supposed to be the “lending institution of last resort” for farmers. It was created to save America’s family farmers as they struggled after the devastating 1930’s depression. But Black farmers then and up to now have never been able to access the loans and other program services at the USDA in an equitable fashion. In fact, in 1982 the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights reported that the primary reason Blacks had lost land was because of the USDA itself and lack of services.

In the USDA regulations, in fact, it states that the USDA offices are supposed provide loan applications and assistance to farmers in filling out the applications. The USDA is supposed to offer loan servicing advice and opportunities for farmers who are having trouble making their payments. If approved for a loan, the payments are supposed to be provided in a timely fashion. These are just some examples.

For Black farmers, however, in most instances the USDA office would not even provide a loan application. And if the farmer did receive an application and was approved for a loan, in many instances the loan came too late to plant that year’s crop. Black farmers were also in many instances given a “supervised account” where they did not receive the money outright but were required to go to the USDA for the loan officer or supervisor to write the check for supplies, etc.

The consequences of all of this has been costly for Black farmers because invariably they would have to get loans from supply houses or banks at exceptionally high interest rates or they went without and sought other jobs to make a living. Often land was lost and marriages destroyed.

A settlement agreement for the class action lawsuit was approved on April 14, 1999, and the deadline for submitting a claim as a class member was October 12, 1999.

Because it became clear that many Blacks where not aware of the settlement, on July 14, 2000 Judge Paul Friedman in the U.S. District Court ruled that individuals could file a petition explaining why they missed the 1999 deadline. Close to 90,000 individuals filed a late petition up until June 18, 2008.

Further, thanks to the Congressional Black Caucus a provision was inserted in the 2008 Farm Bill permitting individuals who had submitted a late-filing request under Pigford to submit a claim form. This portion of lawsuit for the “late” claimants became known as Pigford II.

Thankfully, in November 2010, Congress appropriated $1.25 billion for those Pigford II claims.

Like the original Pigford case, the Pigford II settlement provides both a fast-track settlement process and higher payments to potential claimants who go through a more rigorous review and documentation process. A moratorium on foreclosures of most claimants’ farms will remain in place until after claimants have gone through the claims process.

In some states, there are meetings being held suggesting, unfortunately, that it’s still possible to get into this lawsuit. This has led to considerable misinformation circulating around the South about who is entitled to seek an award. One thing’s for sure: No one should have to pay money to be part of the Pigford lawsuit. Class counsel lawyers will help fill out claims at no cost. There is also assistance from community advocates, like the staff of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund and other farmers’ groups in the Network of Black Farm Groups and Advocates.

Many original claimants are now deceased. There are provisions in the settlement for their next of kin or heirs to file a claim on their behalf. Persons filing on behalf of a deceased relative must furnish a death certificate for the claimant and must know the details and circumstances of their farming operation and USDA loan or non-loan program denial.

As there is a finite sum of money for the settlement, which has to be used to pay all legal, notice and administrative expenses, as well as pay the farmers, the judge has ruled that no funds for successful claims will be distributed until after the claims period and the evaluation of all claims. This means that funds won’t be distributed until late 2010 or early 2013.

If you’re an African-American farmer and have questions about whether you’re in the lawsuit, call EPIQ, the lawsuit administrator, at 877-810-8110.

For years African-American farmers were denied access to USDA funds and services. Now we have an opportunity to correct this wrong.

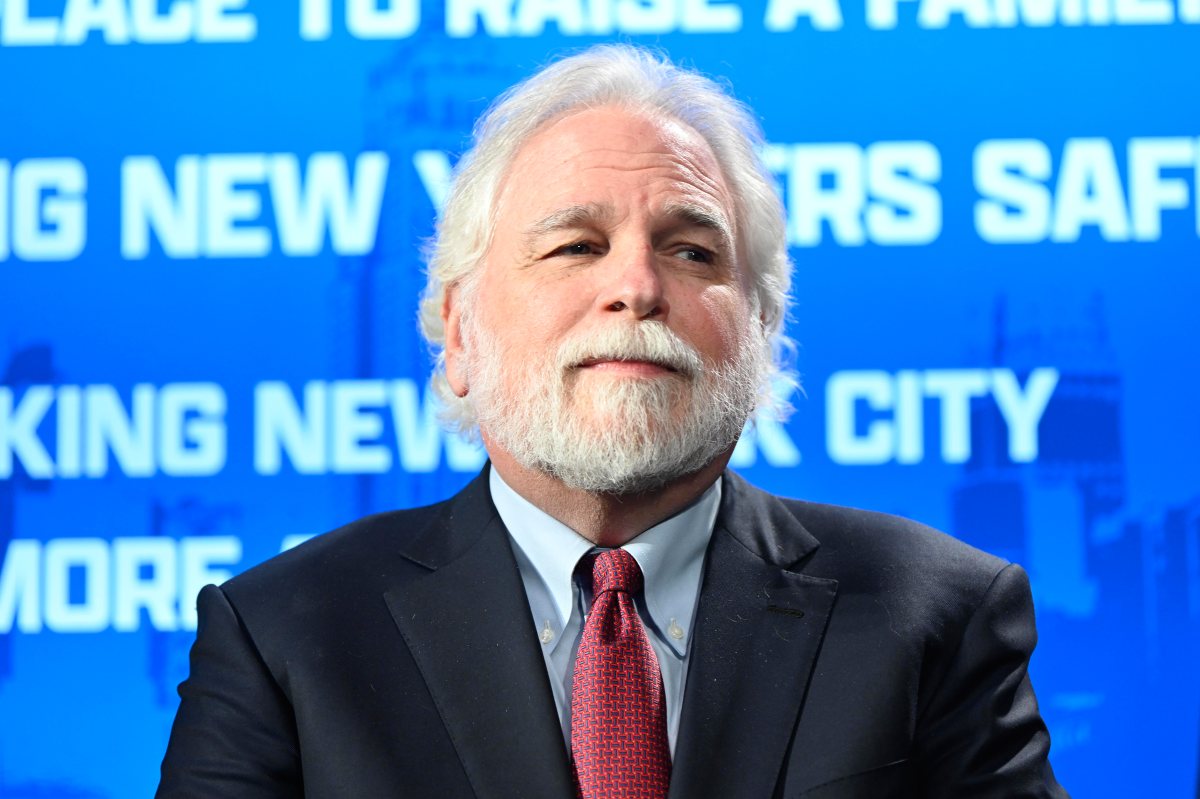

Paige is executive director of the Federation of Southern Cooperative/Land Assistance Fund.