Jamaica-born Lebert “Sandy” Bethune always knew he was privileged to be among a distinguished few.

From the 1950’s when he attended the all-boys, elite Kingston College high school — where its Latin motto Fortis Cadere cedere non potest translates “The Brave May Fall but Never Yield” — as a teenager he broached excellence among his peers, manifested through sports, literature and virtually every form of competition.

And while that vantage enabled access, privilege and an advantage, Bethune never imagined he would be an associate of El Hajj Malik Shabazz, America’s iconic advocate for civil and human rights who is world renowned as Malcolm X.

Bethune lived his school’s mantra and when his parents summoned him to migrate to join them here his grandmother added a Jamaican proverb to his glossary —“you are going to America to drink milk not to count cows.”

Jamaicans have a unique way of communicating and that bovine parable translates to meaning “we should conduct business in a straightforward manner. It also means that one should capitalize on the opportunities presented not waste time talking about them.”

The young Bethune heeded both admonitions and after arriving here to join his parents asked them for a cash advance to travel to Paris, France where he could interact with like-minded would be scholars, authors, poets and literary adventurous Blacks who made an impression on his ambitions.

Richard Wright had already paved the way.

Acclaimed for the 1940 bestseller “Native Son” and his 1945 autobiography “Black Boy” Wright’s migratory path from the south, mid-west, New York and ultimately Paris, France resonated as one Bethune was intent on following.

His generous and trusting parents obliged and enabled the European adventure.

Soon after his arrival there he enrolled at the University of Paris where he quickly secured membership into a fraternity that included some of the most conscientious Black students.

Unfortunately, Bethune missed an opportunity to meet the main scholar he emulated. Wright died of a heart attack on Nov. 28, 1960 in Paris.

However, Bethune was able to establish a significant presence in the younger Black expatriate intellectual circle. His friendships included James Baldwin, William Gardner- Smith, drummer Art Taylor, Dexter Gordon, Richard Wright’s widow, Helen and their daughter, Julia.

He interacted with Francophone writers such as Aimee Cesaire, Leon Damas, Alioune Diop — all seminal advocates of “Negritude” — a Pan Africanist stance for anti-colonial, anti-racist literature.

His poetry and fiction were first published by Presence Africaine, a respected magazine among intellectuals throughout Europe.

One of his most treasured memories is Bethune’s friendship and mentorship with Langston Hughes, which spanned Paris, New York and Africa’s Tanzania.

Hughes even penned a poem in dedication to Bethune.

Recently, during a rare screening at Lincoln Center’s 24th NY African Film Festival, Bethune reflected on the period he lived in Paris and showed his 1964 documentary “Malcolm X:Struggle For Freedom.”

Filmed during Malcolm’s X’s trip to Europe it features interviews filmed during the Pan-African proponent’s trip to Europe and Africa.

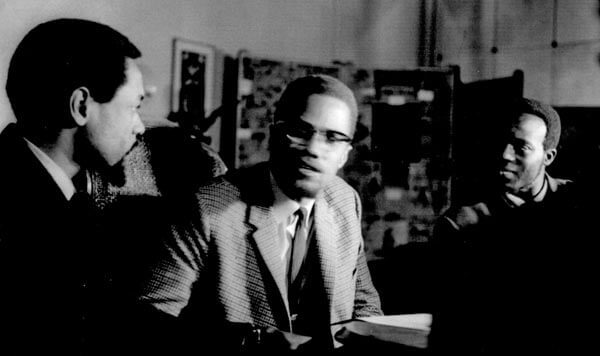

Interspersed with scenes of African rebellion, the black and white, grainy document shows Bethune sitting next to the FBI’s most feared American Black men.

“The film first started as an informal interview at the Paris home of the late French cartoonist, Bob Sine, an original founder of Charlie Hebdo magazine,” Bethune recalled.

Bethune said he was invited to the home of his friend and was shocked when he arrived there to see the Muslim advocate sitting casually as if he was just another guest or friend.

Although he had requested an interview with the prominent American he never imagined the possibility of a one-on-one question and answer moment.

“Malcolm provided Carlos Moore, John Taylor, two other African-American students and I with the sit-down private interview we requested. The uniqueness of the film is that it took place in an informal, relaxed setting -— with a comfortable Malcolm, attended by a small group of five young African Americans, and the security and hospitality of Sine, a former French Resistance Partisan,” Bethune said.

“The interview was recorded with a hand held 16mm camera. Malcolm’s only request in return for the interview was for us to take him around to some of the cafes and places in Paris where he might meet with African-American, artists, students and musicians. We thus became his guide, his de facto security team and informally the earliest unit of the Organization of Afro American Unity in Europe.”

Malcolm X is seen at a time when his views were evolving following worldwide travel.

Weeks later, Bethune attended Malcolm X’s historic “Union Debate on Human Rights” at Oxford University in England.

A few months after, Malcolm X was assassinated in Harlem.

“That Brother Malcolm was assassinated only months later, rendered our interview with him, a unique retrospective in a modern pictorial medium, which now comprises the heart of ‘Malcolm X: Struggle for Freedom,’” Bethune explained.

The film covers a wide array of topics including the role of women in the struggle for Civil Rights; the significance of China’s newly acquired nuclear bomb and the importance of the unity of Africa for the Black human rights struggle in the diaspora.

After the screening, the noted filmmaker, poet, author and scholar candidly presented a snippet of his experiences as a Black expatriate in Europe during the turbulent1960s.

Aside from his milestone documentary, he also introduced “Jojolo: a Profile of a Glamorous Haitian Model-Actress Living in Paris.”

“In the film ‘Jojolo’ I wanted to portray a facet of Black female identity, seen through the eyes of a young Haitian woman working in Paris in 1966, as a Dior fashion model and actress,” Bethune said.

For both his films Bethune attracted moral and material assistance from the legendary Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens and encouragement from Senegalese filmmaker Sembene Ousman.

Bethune’s literary work as a writer has been featured in groundbreaking Black Arts Movement literature.

He has written short stories that were included in Langston Hughes’ anthology “The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers,” poetry in ”Black Fire,” edited by Larry Neal and Amiri Baraka; and an essay on Malcolm X in Europe in John Henry Clarke’s “Malcolm X:The Man and His Times.”

Bethune has taught at SUNY and at the University of The West Indies.

He holds a Bachelor of Science from New York University and post graduate degrees in anthropology and education from Columbia University.

He resides in New York City with his wife April, and their daughter Simone.

He is currently preparing a new collection of his poetry for publication later this year.

Catch You On The Inside!