KINGSTON, Jamaica (AP) — When English teacher Faith Linton first proposed translating the Bible into Jamaica’s patois tongue in the late 1950s, most people who heard the idea shook their heads.

Some on the deeply Christian island believed it was sacrilegious. Others opposed it because the unique mixture of English and West African languages was widely disdained by the elites as a coarse linguistic stepchild to English, which is the only official language in this former British colony.

“There was shock at the mere suggestion,” said Linton, now 81, a longtime board member of the Bible Society of the West Indies. “People were deeply ashamed of their mother tongue. It was always associated with illiteracy and social deprivation.”

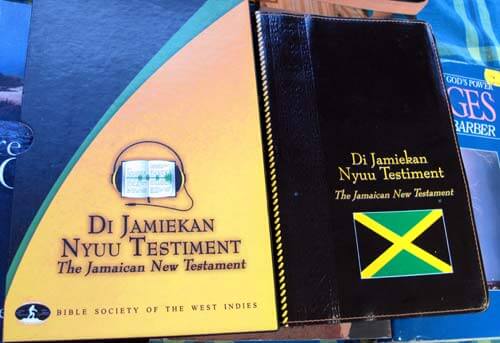

Decades later, Linton’s vision is becoming a reality: After years of meticulous translation from the original Greek, the Bible Society is releasing in Jamaica print and audio CD versions of the first patois translation of the New Testament, or “Di Jamiekan Nyuu Testiment.”

The battle lines have softened somewhat, but there is still substantial opposition to patois in the pulpit. Critics say it will dilute Scripture and undermine the already weak hold many poor Jamaicans have on standard English. Advocates see it as a bold, empowering move that will finally affirm the indigenous tongue as a distinct language in Jamaica.

For patois expert Hubert Devonish, a linguist who is coordinator of the Jamaican Language Unit at the University of the West Indies, the Bible translation is a big step toward getting the state to eventually embrace the creole language created by slaves.

“We’ve now produced a major body of literature in the language, whatever people may think about it one way or the other. And that is part of the process of convincing people that this thing is a serious language with a standard writing system,” Devonish said.

The Rev. Courtney Stewart, general secretary of the regional Bible society, said there is a widespread conviction that Scripture is best understood in a person’s spoken tongue.

He predicts many Jamaicans will be inspired to hear and read the translation in which the shortest verse — “Jesus wept,” following the death of Christ’s friend Lazarus in the Gospel of John — becomes “Jiizas baal.”

In the depiction of the angel Gabriel’s visit to the Virgin Mary that foretold the birth of Jesus, the New King James Bible’s version of Luke reads, “And having come in, the angel said to her, ‘Rejoice, highly favored one, the Lord is with you; blessed are you among women.’”

The patois version says: “Di ienjel go tu Mieri an se tu ar se, ‘Mieri, mi av nyuuz we a go mek yu wel api. Gad riili riili bles yu an im a waak wid yu aal di taim.’”

“It’s extremely powerful for people to hear Scripture in their own language, the language they speak and think in. It goes straight to their hearts and people say they are able to visualize it in a way they’ve never experienced before,” Stewart said.

On the other side, some religious leaders, Anglophiles and other critics characterize Jamaican patois as a rowdy, ever-changing vernacular or “lazy English” that is fine for the playground or market but entirely inappropriate in a place of worship.

“Patois is not potent enough to be able to carry the meaning of the Gospel effectively. It just does not have the capacity to properly reflect the word of God,” said Bishop Alvin Bailey, who leads the evangelical Holiness Christian Church in the southern city of Portmore.

While most words in Jamaican patois have English origins, much of its grammar derives from the languages of West Africa, so it can be nearly incomprehensible to foreigners. The language was created by slaves who were brought to the island by European colonizers, and some say it was designed to prevent slave masters from understanding their words.

Despite the low view some Jamaicans hold for patois, nearly all islanders, regardless of class, can speak and understand it. Those who speak standard English fluently, mostly people from the middle and upper classes, tend to use patois for emphasis, to affect a down-to-earth persona or to talk to someone of a lower class.

The New Testament translation was recently released in Britain, where there is a large Jamaican diaspora.

“The reaction was curiosity at first, mixed with some skepticism, surprise and amusement when the words were spoken, but quite quickly replaced by enthusiasm and admiration,” said Matt Parkes, fundraising director for the Swindon, England-based Bible Society.

In the central England town of Northampton, the Rev. Dennis Hines of the New Testament Church of God said the patois Bible has been received well, especially in prisons where he works as a chaplain and inmates of Jamaican heritage are clamoring for a copy.

“Just to know that there was a Bible in their native tongue has made people feel really proud and excited,” said Hines, who was born in Jamaica but moved to Britain when he was a boy.

The translation is a touchier subject in Jamaica, where activists are pushing for patois to be granted official status alongside English and used in classrooms.

“It will be a process of years, probably, in which some will like it and some won’t, and then an increasing number will eventually accept it over time. That’s the trajectory I see,” Devonish said.

Clive Forrester, who teaches the Jamaican tongue at Canada’s York University, said the biggest obstacle to launching a patois Bible on the island has always been a psychosocial one, not a linguistic one.

“The language can handle any concept or idea in the New Testament. It’s the average Jamaican speaker who has a hard time accepting Jamaican Creole in written contexts and especially one as formal as the Bible,” he said.

Most words in Jamaican patois, like other English Caribbean patois, are English words filtered through a distinct phonetic system with fewer vowels and different consonant sounds. Patois is written phonetically to approximate these differences. So in patois, the English “girl” becomes “gyal.”

A small amount of patois words, between 5 percent and 10 percent, are of African origin, like “nyam” for “to eat.” But the greatest divergence from English is in grammar, which has origins in the languages of West Africa.

An example of West African grammar in Jamaican patois is the way verbs are formed in the past tense. Instead of using a suffix like “ed,” as in “walked,” a patois speaker puts a word before a verb, like “deh.” The English “I walked” becomes “me deh walk” in patois. The same is done in Haitian Creole by adding “te” before a verb to indicate past tense.

Over the years, the Bible has been translated into hundreds of obscure languages and dialects, among them the Ga language of Ghana, the Mi’kmaq spoken mostly by Indians in eastern Canada, and Gullah, which is largely spoken by African-Americans in isolated coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia.

The advocates of Jamaican patois are thrilled to see their day finally arrive, particularly with the island marking its 50th anniversary of winning independence.

“I am convinced this will have an impact on Jamaican people in every way – academically, psychologically, spiritually,” said Linton, who spoke nothing but patois for the first 12 years of her life.

___

David McFadden on Twitter: twitter.com/dmcfadd