A new report and interactive map just released by the Center for Effective Government finds that people of color and poor residents are significantly more likely to live near dangerous chemical facilities than white and non-poor residents in the United States. All 50 states were graded based on these unequal dangers, and more than half of states received D’s or F’s.

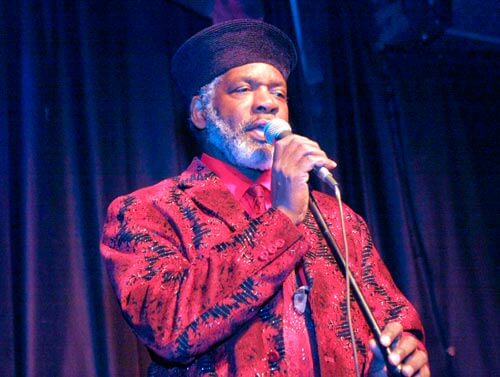

“Our nation’s chemical policies are failing to protect our most vulnerable populations,” said Ronald White, director of regulatory policy at the Center for Effective Government and one of the co-authors of the report. “These include children and the elderly, who are the most susceptible to chemical hazards and among the least able to evacuate should a disastrous release occur.”

The report, Living in the Shadow of Danger: Poverty, Race, and Unequal Chemical Facility Hazards, looks at the 23 million residents living or attending school within one mile of facilities so hazardous they are included in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Risk Management Program. Residents with incomes below the poverty line and people of color — especially children — face the greatest dangers.

People of color make up nearly half the population near dangerous facilities (11.4 million), and they are almost twice as likely as whites to live near these facilities.

Nearly one in 10 U.S. schoolchildren (4.9 million) attends one of the 12,000 schools that are located within one mile of a dangerous chemical facility.

The greatest disparities are among poor children of color. For example, poor Latino children are almost twice as likely to live near dangerous facilities as poor white children are.

According to Michele Roberts, national co coordinator of the Environmental Justice Health Alliance, “It is important that this report is being released at the celebration of the life of Rev., Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Still, today, we ask, how long must race be a factor and how many lives must be tragically lost in order to get the justice our communities deserve? “

These racial and income inequalities exist across most states. Massachusetts and Wisconsin received F’s, and an additional 26 states (primarily in the Southeast and Midwest) received D’s. Only one state — New Hampshire — received an A, in part because it has so few hazardous facilities.

We can do better. The most important step is for the EPA to require all facilities to shift to safer chemicals and technologies where feasible. Many facilities (including all of Clorox’s bleach manufacturing plants) have done so voluntarily, removing the danger to millions of residents. However, until companies are required to do so, most will conduct “business as usual” and continue to put communities in danger.

State and local governments must also be part of the solution. State and municipal governments should conduct assessments to gauge the potential impact of hazardous chemical facilities on fenceline communities; examine possible disparate impacts on people of color, poor residents, and other environmental justice communities; and require “buffer zones” between these facilities and homes or schools.

“We have the solutions at hand. Let’s act now to prevent yet another catastrophic chemical disaster,” said Amanda Starbuck, policy analyst at the Center for Effective Government and a report co-author.

The report, interactive map, and a set of state factsheets are available atwww.foref