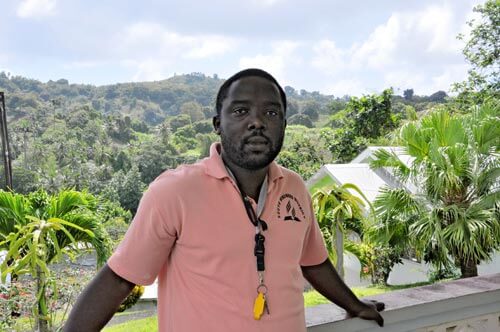

DUMBARTON, St. Vincent, March, 12, 2014 (IPS) – Allan Williams, 32, is an agriculture extension officer in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. But as a trained apiculturist, he has also been involved in beekeeping as a hobby for the past seven years.

He has seen beekeeping grow significantly since 2006, as stakeholders became increasingly aware of its importance to the agricultural sector, and thus an important contributor to economic growth and development.

What’s happening in the Caribbean should not be confused with colony collapse disorder (CCD).

But today, Williams is worried. Honey production has declined tremendously over the past few years and he blames the changing climate as one of the main causes.

He said unfavourable climatic conditions, such as continued heavy rainfall, reduce the honeybees’ access to nectar and pollen, weakening the colonies, which do not have enough food.

“This threat was very evident over the past decade, occurring exceptionally so in 2009, 2010 and 2013. The weather as you know is very unpredictable and it has definitely affected the production of honey for the last two years, but last year was the most destructive in terms of harvesting,” Williams told IPS.

“Climate change is evident as we see with the unpredictability of the rainfall and the flash flooding in very unusual times of the year.”

Last December, St. Vincent and the Grenadines was among three Eastern Caribbean countries (the other two being Dominica and St Lucia) affected by a slow-moving, low-level trough which dumped hundreds of millimetres of rain, killing at least 13 people, destroying agricultural farms and other infrastructure.

“Most farmers, from what I understand, did not suffer destruction of their hives but they suffered from the torrential rain,” Williams told IPS.

He explained that when there is continuous rainfall “the bees are not able to go out and forage on trees where they could get food, so that really reduced our production and I was really affected by it. For two years we suffered a very unusual rainfall pattern.

“In April, the middle of the dry season, we had continuous rainfall for about three or four days and that impacted out production and we are seeing drier spells in the rainy season so there is a shift in the honey flow season when farmers can harvest,” Williams told IPS.

He said it used to be from February to May and even April, but “we are not able to harvest anything. That kind of change of our weather pattern is due to climate change.”

With just a dozen hives, Williams said that he harvests an average of 30 gallons of honey per year. This figure increases to 40 gallons in a “good year”.

Local honey retails for an average price of 100 dollars a gallon, slightly less than the imported product.

The apiculture industry here, which primarily deals with the production and sale of honey, is now valued at 76,600 dollars. The sector is recovering from an all-time low in 2006, when the honeybee population was almost wiped out by the ferocious Varroa Mite.

Over the last three years, the sector produced more than 1,000 gallons of honey from 477 colonies across the country.

St. Vincent and the Grenadines currently has 54 beekeepers recorded in its database, including nine women.

Rupert Lay, a water resources specialist with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), says climate change has begun to cause difficulties for bee farmers not only in St. Vincent but throughout the Caribbean.

“An interesting indicator occurring currently is the little to no production of honey in the region,” said Lay, who is participating in the USAID-funded Reducing the Risks to Human and Natural Assets Resulting from Climate Change (RRACC) project that is being implemented by the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS).

“This can be linked to the unpredictable weather patterns affecting farmer’s beehive colonies and thus honey production,” he told IPS.

“These events are disrupting farmers’ livelihoods which in turn affect adversely the fabric of society and livelihoods, including education. A farmer’s stress can be recognised by his or her children, thus creating worry which leads to decreased attention spans in the classroom manifesting in poor performance,” Lay added.

Williams pointed out that what’s happening in the Caribbean should not be confused with colony collapse disorder (CCD), a phenomenon in which worker bees from a beehive or European honeybee colony abruptly disappear.

While such disappearances have occurred throughout the history of apiculture, and were known by various names, the syndrome was renamed CCD in late 2006 in conjunction with a drastic rise in the number of disappearances of Western honeybee colonies in North America.

Colony collapse is significant economically because many agricultural crops worldwide are pollinated by honeybees.

According to the Agriculture and Consumption Protection Department of the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organisation, the value of global crops with honeybees’ pollination was estimated to be close to 200 billion dollars in 2005.

Williams listed other constraints to the development of the apiculture industry as the lack of appropriate sites for apiary establishment; exotic pests and invasive species; lack of equipment; aerial spraying and lack of staff in the apiculture unit.

For Ricky Narine, a beekeeper in Barbados, the toughest challenge right now is saving the bees.

“We are trying to save the bees. A lot of people out there are using a lot of chemicals that are killing them and they don’t realise that without bees the environment is going to suffer. As much as you tell them they still do it,” he said.

“They can call us or use something safer. There are a lot of different insecticides that you can use that are bee friendly. They might be a dollar or two more but they are bee friendly and will not kill the bees.”

IPS/Desmond Brown