“If humankind could live by the principles of voodoo, of community and tolerance and sharing, we could go so far,” said Erol Josué, singer, dancer, and one of Haiti’s most vital and beloved artists.

Josué invokes the spirits, known as Iwa, to invite healing and tolerance, as he explores his country’s uneasy journey — and his own — in his sophomore album, “Pèlerinaj” (Pilgrimage), available March 24 on Village Hut Records.

Produced primarily by New York City-based Charles Czarnacki, its 18 tracks blend sacred chants and traditional rhythms like dogo, noki and fla voudoun with funk, jazz, rock and club-friendly electronic music.

“Pèlerinaj” – Pilgrimage in Haitian Creole – tells the story of Josué’s own pilgrimage.

Ordained at 17 as a priest of voudoun — voodoo, the centuries-old African Diasporic religion — Josué soon became part of the Haitian Diaspora.

Over two decades living in Paris, New York and Miami, Josué founded or was integral to a dazzling array of music projects and dance ensembles.

The “electro-voudou” sound he developed in the New York club scene, with DJ Val Jeanty, led to his first album, “Régléman,” in 2007.

A 2009 voodoo documentary, followed the cataclysmic 2010 earthquake, brought Josué back to his native country, completing his pilgrimage.

As director of Haiti’s National Bureau of Ethnology, a position he has held since 2012, Josué continues to introduce Haitian voodoo culture to universities and institutions across the United States.

On “Pèlerinaj”, he sings – in French and Creole – not only of his own spiritual and political journey, but of Haiti’s.

F

rom secret meetings of African slaves and Haiti’s Indigenous Arawak people (“Badji”) to a paean to the resilience of a people who successfully revolted against slavery and colonialism (“Je suis grand nèg”) only to face poverty, human rights violations and natural disasters, Pèlerinaj takes the listener to the aftermath of the 2010 temblor.

“Avelekete” is Josué’s tribute to the earthquake’s victims, calling on those yet to grieve to allow their tears to fall.

“Kwi a” reminds Haitians that they are descendants of freedom fighters who should never use their hollow kwi calabashes to beg; “Pèlerinaj fla vodou” honors the country’s refusal to continue seeking international aid.

Through the country’s travails wind the forces and fates of voudou. “’Fla’ [“Pèlerinaj fla vodou”] is the moment when everything is flowing in the ceremony,” said Josué.

“Pilgrims sing this song as they climb to reach the feet of their patron saint,” he added

He sings of his own pilgrimage — his journey and return — on “Kafou.”

“The crossroads is an important symbol in voodoo. Which path to take – north or south, Paris or New York – is a decision called ‘kafou’,” Josué said. “You put candles, alcohol and food on the crossroads. Then you say thank you, and you go.”

Having opened the album by invoking voudoun goddesses and saints on songs like “Rén Sobo,” “Ati Sole” and “Palave Maria,” Josué closes it with “Kase Tonèl,” a live recording of a voodoo ceremony and the festivities that follow.

A roster of global musicians helps Josué and producer Czarnacki link together the singular journey of “Pèlerinaj.”

French/Guadeloupean jazzman Jacques Schwarz-Bart plays saxophone and co-arranges three songs; master percussionist Bauvois Anilus and guitarist Mark Mulholland accompany Josué on his Haitian homecoming on “Kafou”; and French composer Arthur Simonini provides the subtle piano and orchestral arrangements on “Tchèbè Tchèbè,” celebrating slave-turned-revolutionary leader Jean-Jaques Dessalines.

Czarnacki said “Pélerinaj” is, “if you like, a concept album.

“These are songs that tell of ancient wisdom and clandestine rendezvous that variously name check the queen of the night (‘Rén Sobo), the female sun deity (‘Ati Sole’), the blessed vodou Virgin (‘Palave Maria’) and on ‘Erzulie’ – a sensuous roll out of chants, bells, strings and keys arranged by the Gotan Project’s Phillipe Cohen Solal – the goddess of beauty and mother of the world,” he said.

“Love and sex feature in the rollicking ‘Sim goute w’, whose lyrics warn against infatuation, and advise using the sacred voodoo cross to protect energy, resist temptation,” he added.

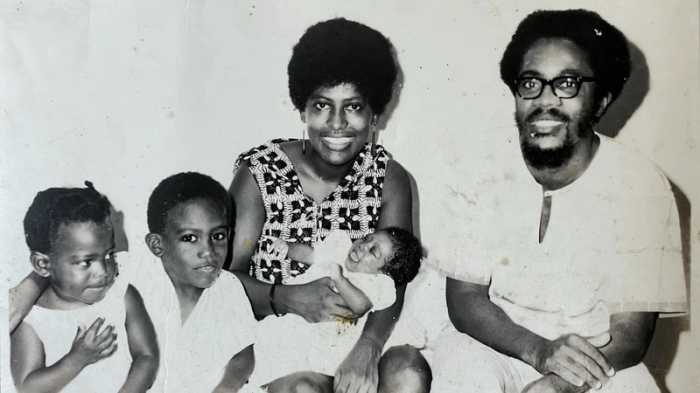

Josué was born in Port-au-Prince, in the residential district of Martissant in Haiti.

Born in voodoo, cradled by traditional music, raised in the family hummus, he was initiated at the age of 17 as a houngan (voodoo priest) by his mother (mambo) and his stepfather.

Today, master of the “Sosyete lafrik Ginen” peristyle, Josué directs the ceremonies and receives for consultations.

He also developed a great knowledge of nature and the plants that heal and officiates as a “leaf doctor,” traditional Haitian medicine, with respect for nature.

“This anchoring and this Voodoo culture are inseparable from his personality, his artistic career on the one hand and his anthropological and ethnological knowledge on the other,” Czarnacki said. “His natural talents and abilities as a singer and dancer first manifested in this religion, from which he draws from the traditional repertoire much of his artistic inspiration.

“The active voodoo priest fed the actor and dancer,” he added. “His music is thus at the crossroads of African-American, Caribbean and European cultures. It is rooted in the traditions of Haitian voodoo, but draws on all sources of inspiration.

“If it is Haiti that he expresses through his shows, it is the voodoo that he wishes to present in a new, authentic and washed-out caricatures,” Czarnacki continued.

“I have had the rare privilege of living my voodoo spiritual life at home, while attending Catholic school during the day,” Josué said. “I never converted and now I can help dispel the voodoo myths. As an artist, I can help make it easier to understand.”