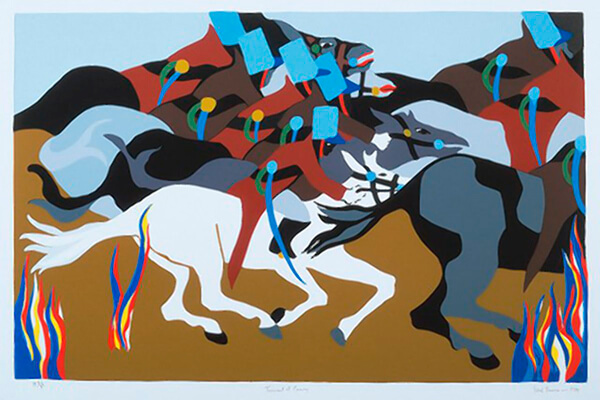

The Haitian Revolution is captured in a new exhibit here that features 15 rarely seen silkscreen prints about Toussaint L’Ouverture, the Haitian ex-slave turned general who led a revolution that ultimately wrested the Caribbean island from French control and ended slavery.

According to The Afro, a weekly Baltimore, MD-based newspaper, the exhibit – at the Phillips Collection in Northwest Washington, called “To Haiti Let Us Go” – shows works from late African-American painter Jacob Lawrence, who created the series between 1986 and 1997.

It’s based on an earlier series of paintings Lawrence executed on the same topic in the 1930s, said Elsa Smithgall, the museum’s curator. The exhibit, which opened on Saturday, closes April 23.

The former French colony, with its massive coffee and sugar exports that relied on slave labor and used brutality to keep slaves in check, was the most profitable colony in the Americas by the 1760s, according to the US Department of State’s Office of the Historian.

L’Ouverture was born into slavery in 1743 in Haiti, and led a massive slave insurrection on the island against White planters in 1791, The Afro said.

Three years later, it said the French National Convention abolished slavery in France and in all of its colonies.

The Afro said L’Ouverture rolled out a Haitian constitution in 1801 that declared him governor-general for life, according to Brita

But Napoleon Bonaparte sent troops to invade Haiti the next year in a failed attempt to restore French control and slavery to the island, The Afro said.

It said French officials invited L’Ouverture to France under false pretense; and, under Napoleon’s orders, French soldiers kidnapped and imprisoned him because they were fearful L’Ouverture was planning another uprising, according to Brita

The Haitian Revolution persisted until after the Haitians defeated Napoleon’s army at the Battle of Vertieres in 1803, The Afro said.

The following year, it said Haiti became an independent state, and with it, the world’s first Black republic and the second country in the Americas, after the United States, to earn its independence.

The Afro said France retaliated against Haiti in 1825 by imposing a trade embargo that forced Haiti to pay 125 million francs to the French for the loss of its slaves.

“Haiti, relegated to borrowing money at unfavorable rates from foreign banks, did not repay the debt until 1947,” The Afro said. “Haiti is now the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere and one of the poorest in the world, according to the World Bank.”

Lawrence, who died in 2000, captured multiple stages of the Haitian Revolution — some depict violence and others show soldiers quietly plotting the next maneuver, according to The Afro.

“The thing about Toussaint L’Ouverture that Lawrence is really interested in expressing here, that he does in so many of his works, is the struggle, and the part about searching for freedom and doing away with oppression,” Smithgall said.

The Afro said Lou Stovall and his wife, Di Stovall, who are Washington, D.C. residents, own the collection, and were friends with Lawrence and his wife, Gwendolyn Knight, for decades.

Lou Stovall, 79, and Lawrence forged their friendship in the 1960s after one of Stovall’s professors introduced them at Howard University, The Afro said.

It said Lawrence later tapped Stovall, a master print maker, to print the silkscreen images that comprise “To Haiti Let Us Go” in order to “dramatically capture the revolution and suffering Haitians experienced under French colonial rule.”

The Afro said the collection, one of the first to bring substantial recognition to Lawrence, also meant a great deal to the artist, and showed his lifelong passion for the human condition, according to Stovall.

“Jake, first of all, learned about the Haitians and their predicament with France and with Spain through reading, and he was concerned, of course, about the plight of all people,” Stovall said. “He wanted everyone to be free.”

Phillips officials hope visitors understand how this series and its depiction of freedom, social justice and the fight against oppression paved the way for Lawrence’s famous Migration Series, which depicts African Americans fleeing the racist South for better lives in the North, according to The Afro.

“I want them to feel encouraged that you have with Haiti the example of the first Black western democracy,” Smithgall said. “Around the world, there’s still the need for us to affect a lot of political change to stamp out oppression.”

The Afro said Phillips typically houses Lawrence’s Migration Series, but museum officials loaned it to the Seattle Art Museum.

“To Haiti Let Us Go” temporarily replaces it, The Afro said.