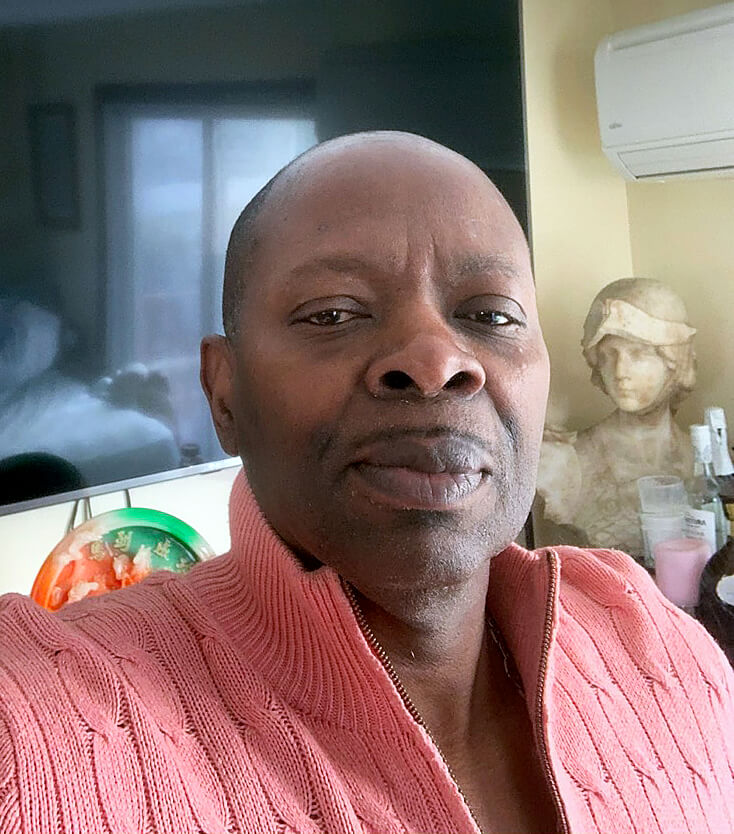

Ronald “Wenick” King, a former civilian construction supervisor, told Caribbean Life, he was among a group of volunteers who rushed to ground zero on Sept. 14, three days after the terrorist attacks on 9/11.

He said he was compelled to show his gratitude to the country that had done so much for him and for so many others.

King, who immigrated from Guyana in 1978 at age 21, recounted that after the terrorist attacks, he could not sleep, thinking who could have done such a terrible thing to America, and jumped in to help in the recovery.

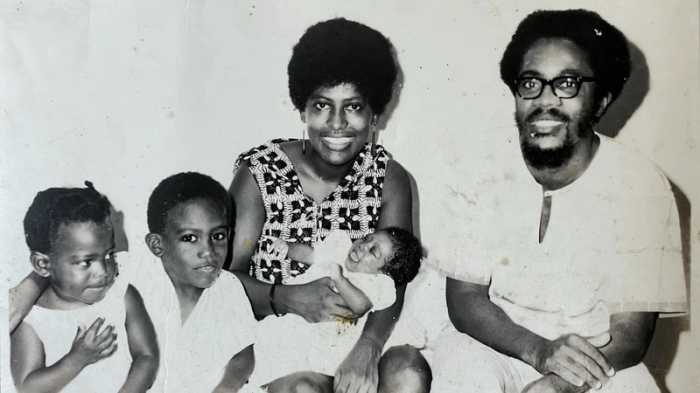

“I can’t help going back to my uncle, Rudolph Dunbar, because my family came to this country on account of him. He lived here and would always write my mother to say, there was something special about America,” said King who was inspired to leave his small town of Linden for a future in this country.

With these sentiments in mind, King took a member of his work crew and abandoned his job at New Roads Construction in Manhattan to join a volunteer line at the devastated site, where more than 2,000 people perished.

He labored for long hours, combing through tons of rubble, among a bucket unit, with only one concern, that he could be crushed by one of the steel beams left from the imploded twin-towers.

Nevertheless, he kept going back to the site day after day, hoping to get closure, since it was believed thousands of people were still trapped and needed help getting out, a sad situation that became worse by the day.

He said while working on piles of rubble, he wore protective gear including face mask, but remembers replacing soot-covered masks and occasionally removing them to take a breath, unaware that the toxic air at Ground Zero could have affected his lungs.

The Valley Stream, Long Island, resident, after one month, returned to his job and was pleasantly surprised when his boss Jerry Romonoff paid him a salary.

He felt good and settled back into his normal routine, thinking, and annoyed, that other volunteers were complaining about having breathing problems.

Unfortunately, months later, King fainted on the job, and was rushed to the hospital. The attending doctor at that time advised him that his fainting spell was a reaction to him breathing in human remains, while working at the catastrophic site.

Just then, the WTC Committee had opened a monitoring clinic, and King was given a clean bill of health, but subsequently, another test by his doctor showed he was suffering from COPD.

Another sample was taken later and King was diagnosed with Pulmonary Fibrosis and prescribed, Symbicort and Spiriva, which he said have been very helpful with his breathing.

King who refused psychotherapy treatment for his post-traumatic stress disorder, that had affected his work and family environment, is still working through his anger issues.

He said he has suffered much loss that included financial loss, that did not cover sick days, as well as his job as a supervisor he left in 2009, much to the disappointment of his workmates and boss who presented him with a letter of commendation.

King said he had no regrets and wanted to give the accolade to his uncle, Rudolph Dunbar who inspired him to give back.

Dunbar, a WW ll veteran, died in 1988. During the 1930s and 40s he was a leading journalist and a foreign and war correspondent for the news agency representing African American newspapers, was credited with the heroism of saving the US 969th Battalion during the Battle of the Bulge in the winter of 1944, but never received an acknowledgement for his bravery.

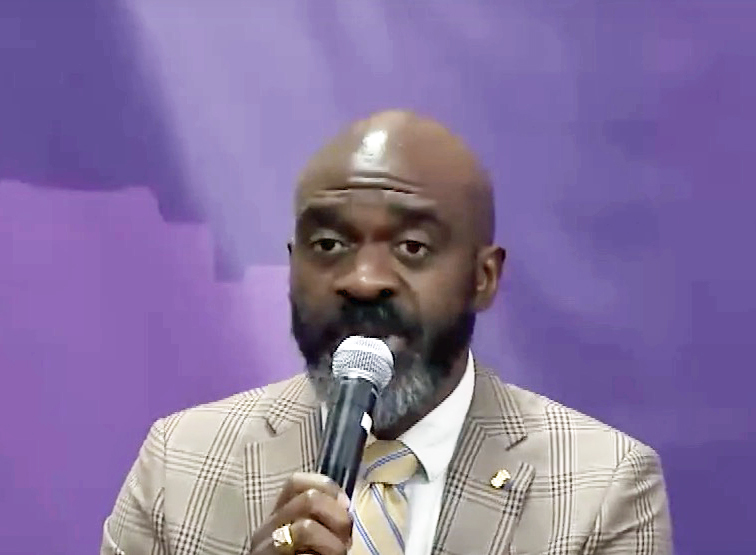

King’s experience at Ground Zero is chronicled in “We’re Not Leaving” by Benjamin J. Luft, M.D., a compilation of powerful first-person narratives told from the vantage point of World Trade Center disaster workers — police officers, firefighters, construction workers, and other volunteers at the site.

While the effects of 9/11 on these everyday heroes and heroines are indelible, and in some cases have been devastating, at the heart of their deeply personal stories — their harrowing escapes from the falling towers, the egregious environment they worked in for months, the alarming health effects they continue to deal with — is their witness to their personal strength and renewal in the ten years since. These stories, shared by ordinary people who responded to disaster and devastation in extraordinary ways, remind us of America’s strength and inspire us to recognize and ultimately believe in our shared values of courage, duty, patriotism, self-sacrifice, and devotion, which guide us in dark times, according to the book’s synopsis on Amazon.com