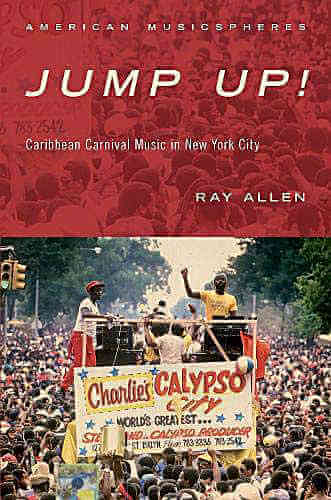

After taking a long and storied look at carnival, Ray Allen, a professor of music and American studies at City University of New York’s Brooklyn College carved out seven years of his life to compile a scholarly glossary and overview focusing on the totality that defines Caribbean jump up revelry.

According to the author who penned a book he titled “Jump Up” his reason was partly motivated by the fact he genuinely “loves the music.”

From start to finish, page by page, there are 295 other reasons.

“Jump Up” is the first comprehensive history of Trinidadian calypso/soca and steel-band music in the diaspora,” Allen said in his introduction.

“Previous studies have given ample coverage to carnival music in the context of Trinidad but paid nominal attention to the migration and significance of this music outside of the Caribbean.”

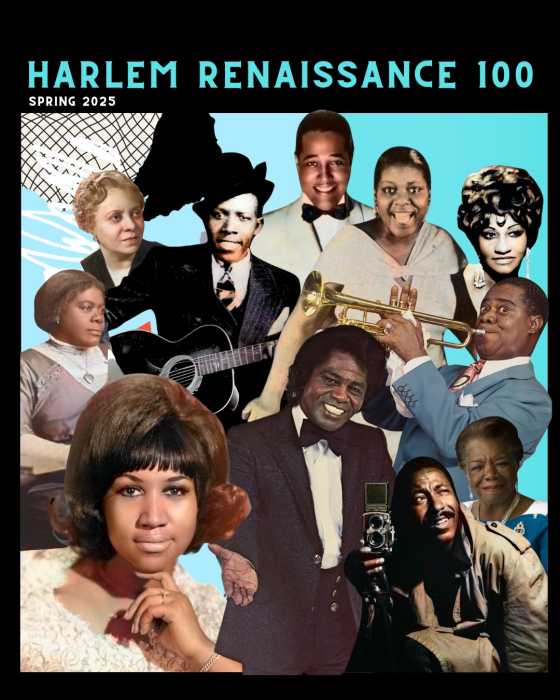

Published by Oxford University Press, the textbook acknowledges the genesis of carnival here beginning with its root in Harlem branching across the United States to bloom with pride and pageantry in Brooklyn each August to September, ending on Labor Day.

A chapter on Harlem carnival hails trailblazing expatriates from the twin island whose mission was to show off their creative talents.

Throughout it hails the 1930s beginning years by scoping out the foreign culture that begged recognition, acknowledgement and freedom in the capital of Black culture.

How it migrated across the Brooklyn Bridge in the 1960s to plant itself in the Caribbean capital of NYC reads like a slow jourvert march to emancipation.

Allen takes painstaking effort to document the many steps trailblazers paced from City Hall to borough hall in order to satiate homesick Trinidadians many of whom yearning for calypso, pan, masquerades and familiar foods.

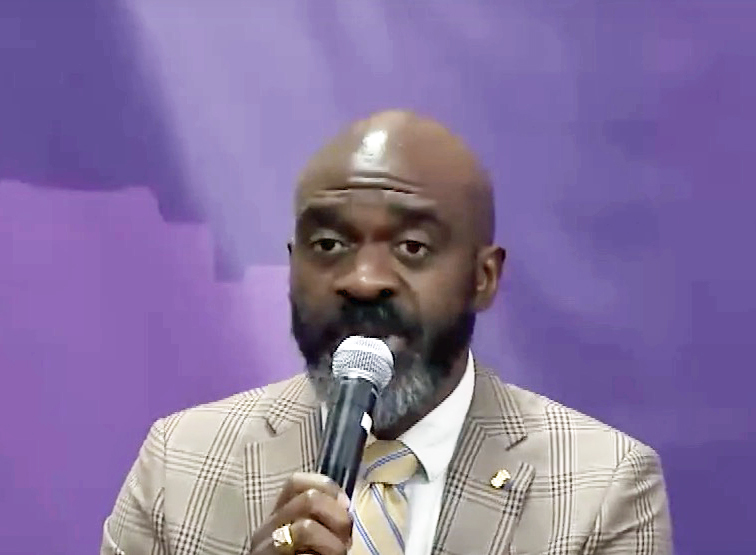

During a recent launch held at Greenlight Books on Flatbush Ave. Grenadian Herman Hall, publisher of Everybodys Magazine agreed that carnival culture is “deeply imbedded in the DNA” of nationals and since migration, Brooklyn is now ground zero for all things carnival — from food to frolic.

Hall’s publication is heavily quoted in this book, partly because throughout the years the magazine has vigilantly and consistently documented the history and progress of the Caribbean region in order to provide context to an underserved immigrant population often ignored by the mainstream media.

Along with articles gleaned from the Black press — NY Amsterdam News, The Daily Challenge — the two outstanding medium, one weekly, the other daily, does not focus on Caribbean news but occasionally dedicates space to highlight certain events — a detailed perspective traced rhymes, rhythms, kings and queens of the genre and a plethora of nostalgic references pertaining to carnival.

Undeniably the trailblazers get their due.

Carlos Lezama, West Indian American Day Association’s trailblazing visionary is deservedly regaled.

Most heartening is an extensive index listing of sources that the author credits.

They include colleagues of this insider — Dawad Philip (Daily Challenge), Peter Noel (Amsterdam New), Gerald Spence (Jamaica), Kim Loy Wong Wing (Highlanders), Don Rojas (Grenada) Charles Baillou (Bahamas) Merle English (Newsday / Jamaica) David Katz (USA) and countless other unsung contributors to the enhancement of the bacchanal.

Unfortunately, not all were acknowledged, missing from the last pages were notations from Tobago-born Rene John Sandy, former Class/Black Diaspora Magazine publisher.

Honorable mentions exalts pioneer Reynolds Caldera Caraballo who among a myriad of attributions also allegedly performed pan alongside Harry Belafonte back in the day.

Rawlston “Charlie” Charles is hailed for his long-serving years providing vinyl enjoyment and production refinement to the genre.

Charlie also gets added kudos with graphic imagery and a nostalgic Labor Day cover photo of one of his decorated sound trucks along Eastern Parkway circa 1982.

A chapter titled ‘Soca versus Reggae versus Salsa versus Kompa’ will be alluring to readers curious about the cross-cultural Caribbean connections in English, Spanish and French territories.

According to a chapter titled ‘Musical Hybridity and Cultural Identity’ Allen contends “Just as music could bring English-speaking Caribbean migrants together, it could also segregate them by providing island-specific cultural expressions.”

Adding that “Brooklyn’s Jamaicans tended to favor reggae, Bajans spouge, Haitians konpa, and Trinidadians, Antiguans, St. Vincentians and Grenadians soca (and particularly the soca popularized by singers from their native island – Swallow from Antigua, Becket from St. Vincent etc.)”

J’ouvert gets a fair share with explanations on how the pre-dawn phenom maintains steel as the engine to drive masses of dedicated masqueraders willing to maintain an Africa-rooted essence that allegedly birthed the tradition.

And the crowned royalties — King and Mighty Sparrow, Lord Nelson, Count Robin, Queen Calypso Rose, Singing Francine and others are regally hailed.

Hall maintains high hopes for pan because of its global appeal and ever-expanding reach with prominence on every continent — Asia, Africa, Europe, South America and North America.

He explained that a preponderance of young US-born pannists now dominant in many pan orchestras, the future seems bright.

However, he proposes a bleaker forecast for the future of carnival due to waning numbers of masquerading bands registered for participation.

Gentrification too may also alter the pervasive aspects.

At the end of the informative and insightful launch — guitarist Calvin Jones and Garvin Blake, double second pannist — endorsers of Allen’s “Jump Up” treated the VIP guests to pan samplings of Sparrow’s “Afraid” and “Black Orpheus.”

Catch You On The Inside!