Back in another century, the government of Jamaica campaigned with encouragement to nationals to support local businesses.

“Be Jamaican buy Jamaican” advanced a mantra everyone could relate to despite the onslaught of foreign made importations into the tiny island.

And although in this century, the common practice there has been focused on emulating everything foreign, when it comes to food, Jamaicans regardless of residencies are inclined to seek out and find food familiar to their native palate.

With that said, there was a time when Jamaican foods were a rarity in this city.

Maras, a food emporium located at Nostrand Ave. capitalized on the need and provided some of the more demanded imports from the Caribbean. Weekend rides on the IRT train to Brooklyn seemed a welcome ritual to navigate. In search of The Jamaica Gleaner, hard dough bread, Milo, Easter bun, tamarind balls, cola champagne and other Jamaican delicacies it was the go-to place to find island eats and treats.

What is now a round-the-way convenience was a sought-after shopping experience only available in that singular outlet that imported goods to appease migrants to the then most populous borough for Jamaican immigrants.

During the same period I recall ambling into a delicatessen on one occasion to experience a rude awakening about my sensibilities.

From the counter, I spotted a golden item I could digest.

Unaccustomed to pizza, hot dogs and burgers, it was pure joy seeing a snack I could relate to – “a patty?” I said to myself.

I recalled buying the item, biting into it and immediately felt nauseous.

It was patty-looking but not the Jamaican snack I imagined but a knish.

Repulsed by potatoes, the disappointment was more than colicky.

In retrospect, patty shops, Jamaican bakeries, eateries and things Jamaican were few and far between.

In the Bronx where White Castle ruled a patty defined anything but the beef-filled baked golden, flaky, nourishment I was accustomed.

As the years passed, Gig Young Bakery debuted at Utica Ave. offering sliced, hot, hard dough bread, bun and cheese, and tasty Jamaican patties.

Tower Isles Jamaican Patties also satiated immigrants by offering lip-smacking food from yard.

Nakisaki, a Chinese-Jamaican restaurant opened on Long Island and in addition to cooking Asian and Jamaican delights won a reputation for serving the best Jamaican stewed peas and rice dinners.

By the 1970s, back in the Bronx it seemed as if an explosion of social clubs, restaurants and vendors claimed Gun Hill Road as the mecca for immigrants from the land of wood and water.

Afterwards it was full speed ahead with Jamaica’s popular phrase, “we lickle but we tallawah” — meaning small yet powerful or some version of the same boasting mettle.

A plethora of accomplishments in the late eighties amplified by Jamaica’s dancehall rhythm revived reggae music as the driving beat to propel movement of Jah people.

SONY Music signed Shabba Ranks to a recording deal and cracked the industry resulting with a decade of prosperity for deejays and entertainers.

Bronx-based Vernon’s Jerk Paradise catered virtually every listening party media and insiders were invited to tune in to new music regardless of genre.

Major record labels helped to propel the demand for Jamaican cuisine by blazing a trail through music.

In addition to Manhattan, the two boroughs jockeyed to capture the niche.

In Brooklyn, double-parked cars hampered traffic where Apache, a fish spot at Prospect Place sold escoveitched fish and crust.

To the uninitiated, crust is a long, flaky, flavorful, rectangular shaped, meatless baked dough.

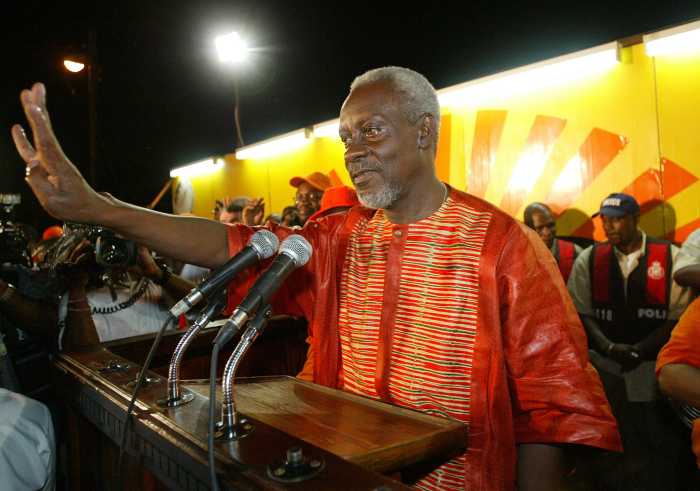

As Jamaicans in Brooklyn rallied to buy Jamaican, Lowell Hawthorne launched his brand in the Bronx.

He named it Golden Krust Caribbean Bakery & Grill.

Crust with a K provided comfort food, nostalgia and relevance to a burgeoning community that longed for soul food from Jamaica.

Just as the golden arches identify McDonald’s as the American burger spot, a golden marquee determined the power of the patty, the might of the immigrant and his entrepreneurial success in “taking the taste of Jamaica to the world.”

Reportedly, the blue on the logo represents the Caribbean Sea and the yellow that brightens the walls and awning of the restaurants mimic the tropical sunshine.

Any patron to any location will also readily acknowledge the Caribbean music played in every franchise.

Hawthorne once said the sound is integral to creating a “Caribbean experience.”

Hawthorne provided ‘festival,’ the long, tall corn replica to crust, ackee patties, Jamaica’s national dish of ackee and saltfish, oxtails, rice and peas, curried goat, cow-foot soup, red peas and gungoo soup, Easter buns, brown-stewed chicken etc.

He established 16 franchises in New York and was emulated by a competitor who launched six Silver Krust West Indian Restaurants in Brooklyn and Queens in order to capitalize on the boon.

His Bronx plant allegedly prepares 24,000 patty batters per hour every day.

Reportedly, staffers work 16-hour shifts each day in order to supply the demand from franchises.

Golden Krust has been a runaway success.

The brand has made its way into the correctional system, the military and inside the hall of prestigious restaurants at Grand Central Terminal.

Single packaged beef, chicken and vegetable patties are sold in Dollar stores throughout.

Reportedly, on the verge of expanding the Midas to the Middle East and Canada, no other patty maker rivals the Golden Krust brand.

When the Jamaica Tourist Board opened a pop-up shop recently to promote the best of the island Hawthorne’s nephew, Steven Clarke — who is director of marketing and public relations– delivered and served free patties to guests.

It was Clarke who faced a barrage of media to explain the family tragedy.

Hawthorne died Dec. 2, seven months and one day after his 57th birthday.

The following day a song in tribute to the president and chief executive officer flooded social media.

“You created Golden Krust… people said you had that golden touch… NY cannot comprehend… we lost a father and friend… Jah know we miss you so much… but your memories will live on… because you created Goldn Krust.”

One week after his untimely death, a candlelight ceremony was held in Kingston, Jamaica at the University of the West Indies.

Simultaneous to that solemn event, a memorial was held at the Gun Hill Road location, the first Golden Krust site in the Bronx.

On a visit to Jamaica, Hawthorne spoke to an audience saying: “I stopped by to tell you to expand your business beyond the shores of Jamaica, into the Americas where there are no borders. Think globally, think export, think Brand Jamaica and explore every opportunity to market our products, our country… to those ready and waiting in the wings.”

“I want to encourage you to stay focused and build a lasting legacy for Jamaica and our people,” he added.

“Don’t be afraid to dream big, don’t be afraid to dream alone. Only be afraid not to dream at all.”

The hope is that the Golden Krust legacy will continue.

During his lifetime Hawthorne gave assurances — “I have a wonderful staff and team and group of family members who are the unsung heroes of the success of this company.”

“My family members are the founding and brave soldiers who shared my vision, dreams and aspiration. They had the faith and trust that I would have delivered, and I think I have done that.”

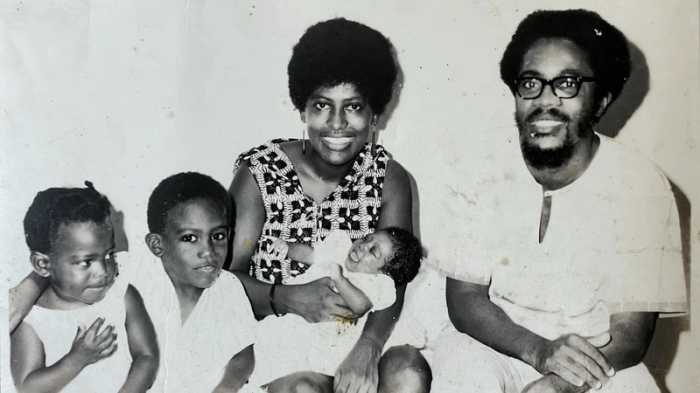

The trailblazing Jamaican entrepreneur who fulfilled the dream of his parents Ephraim and Mavis Hawthorne is being grieved by — wife Lorna, Leroy Hawthorne Haywood, Lorraine Hawthorne-Morrison, Herma Hawthorne, Daren Hawthorne, Omar Hawthorne, Garnett Morrison, Steven Clarke, Christopher Hylton, Kareen Murray, Darren Hanson, Erica Hanson, Stephen Ament, staffers, his country, Caribbean nationals and a myriad of friends and admirers.

A wake is slated to be held from 5 pm to 8 pm on Dec. 18 at the Grace Baptist Church, 52 6th Ave. in Mount Vernon. The funeral will be held the following day at Christian Cultural Center, 12020 Flatlands Ave. in Brooklyn. Viewing at 8 am, service at 9 am.

Catch You On The Inside!