For an island of 166 square miles with a population hovering on 385,000, a prime destination for tourists who crave its pristine beaches, mostly placid blue sea, and vibrant night life Barbados has the makings for contests for land space among residents and tourism investors.

It therefore came as no surprise last week when arguments that were at times rowdy erupted pitting residents against investors over $25 million plans to construct a 10-storey hotel in the south coast area of Worthing, Christ Church, on the inland side of a road running parallel to the beach and a restaurant on the seaside of that road.

At a town hall meeting hosted by the developers as part of a town planning requirement for consultation with residents before certain construction projects are approved, Barbadians’ protests fell into two categories which overlap. There were those objecting because the proposed 10-storey edifice would replace a four-storey hotel and block the view to the sea from their residence in the area; and those who objected to placement of the restaurant as it would reduce locals’ access to the beach and sea.

Resistance based on the proposed height of the hotel not only touches on sea view obstruction for nearby residents, but also on interference with the skyline in a country with few tall buildings.

Currently there is only one 10-storey hotel, and that is topped only by the island’s Central Bank building of 11 floors.

Barbadians see the absence of an abundance of tall buildings as an important feature of the island’s attractiveness for tourists who want to get away from the concrete jungle atmosphere of the metropolis.

The objectors demanding that a wide window to the sea be retained in the area are continuing a fight which reaches back to matters that came to a head in almost 40 years ago when a corporate lawyer for the tourism board, jack Dear, offered a legal opinion that hotels could encroach on the beach to the high water mark.

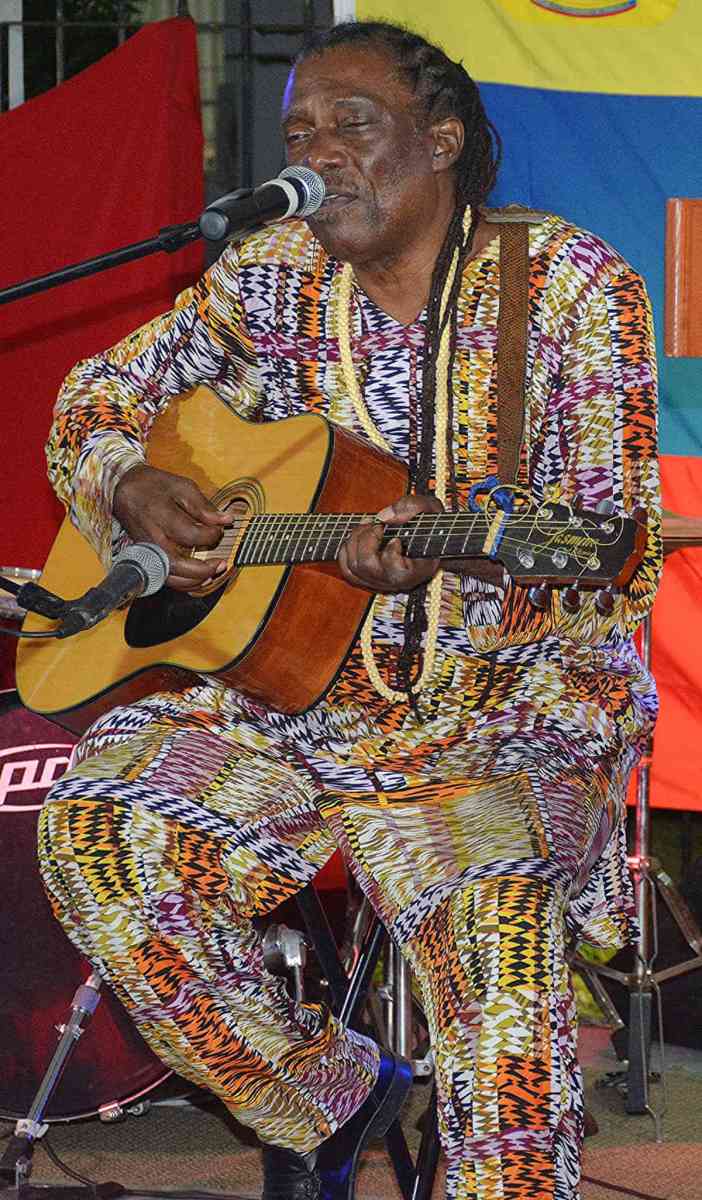

That pronouncement along with the mushrooming hotels on the island’s platinum west coast leaving only alleyways between buildings for residents’ access to the sea caused popular calypsonian, Mighty Gabby, in to pen and release in 1982 the song ‘Jack’ that gained Caribbean-wide popularity as an anthem for those concerned about tourism’s hold and control of these territories.

In spite of Gabby’s ever-popular ‘Jack’ Barbados’ West Coast, the second home of many of the world’s rich and famous, today has very few spots that can be termed windows to the sea.

Those objecting to construction Blue Horizon’s seaside restaurant on Accra Beach are contending its presence will close one of the few surviving windows to the sea on the south coast.

It was then a fitting confluence of history that the Mighty Gabby was among those attending the town hall meeting and emerging again as the leading voice in protest.

“I am saying to you that we, the people of Barbados, will not allow you – I say to you, collectively you – to put that restaurant on that beach . . . That cannot happen . . . It will not happen,” said the now 71-year-old, who is still an active performer on stages in Barbados and other Caribbean territories.

Commandeering the microphone to loud applause from the over 300 persons at the meeting, he said to the developers, “nothing at all on that beach. And if government gives you permission to build, I Gabby will personally go there every day and stop it”.

“You will not be able to fight Gabby. I will get lock up, beat up whatever. I will go and stop it physical and personally. You will not be able to get the work done.”

Gabby’s passionate contribution is believed to have once again appealed to the psyche of the nation as his statements dominated reports in the established media and postings on social media.

The problem for the cash-strapped one-year-old government is that it badly needs the type of foreign direct investment found in this venture because it is unable to borrow on the international market owing to a junk credit rating status it inherited.

With its international business sector coming under increasing threat by organisations of developed countries the island is becoming more dependent on tourism as the major earner of foreign exchange and as a major employer of Barbadians.

According to the Barbados Central Bank, for the first half of this year 208,800 tourists arrived on the island. And the tourism sector accounted for 19.3 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product, equating to $200 million.

This show of resistance however means the administration now must temper the zeal of investors to more suit wishes of inhabitants of the island.