PARIS, March 29, 2017 (IPS) — It’s one of those movie-like spring days in Paris, where blue skies and brilliant sunshine lift spirits after a long, wet, grey winter. Many people are outdoors trying to catch the rays, but Jamaican artist Danny Coxson is not among them. He’s inside a museum in a northeastern neighbourhood of the French capital, with a brush in his hand and tubs of vivid paint beside him, focusing on finishing a portrait of a deejay named Big Youth.

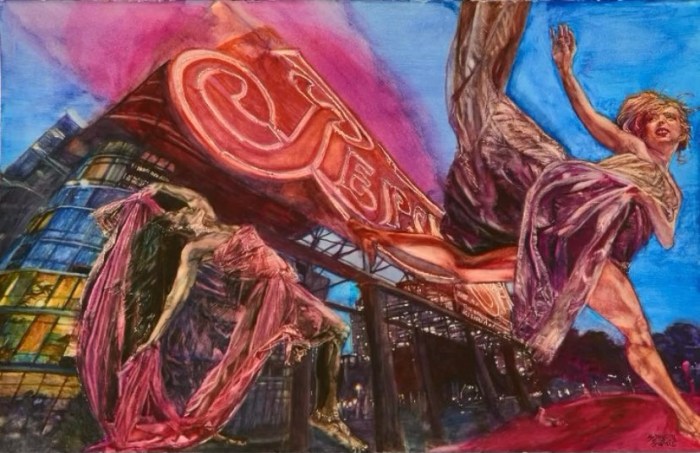

Coxson’s artwork — colourful and precise renditions of Jamaica’s best known musicians — is the “common thread” that links the vast range of items on display in Jamaica Jamaica!, France’s first major exhibition on the history and impact of Jamaican music.

Born in Trench Town, like Bob Marley, 55-year-old Coxson has been painting since he was a young man, but he says he didn’t take it seriously until he was in his early thirties, when he lost three fingers through a machete incident in 1991. Since then, he has devoted his career to painting murals of Jamaica’s singers, producers and sound engineers, holding his paintbrush in the remaining fingers of his right hand.

Through a grant from the Institut français cultural agency, Coxson has been artist-in-residence in Paris since February, painting murals and portraits for the massive exhibition. On this day, he’s an island of calm in the museum, as workers rush around, finalizing the display for the public opening on April 4.

“This exhibition is a good thing for us Jamaicans,” Coxson tells IPS. “But we have to wake up about our own culture because sometimes we don’t value it enough. And look at how people come from so far and take it up.”

Jamaican music and artistic production have contributed greatly to the island’s cultural and economic development, but this is sometimes overlooked, Coxson says. Artists like him don’t receive enough official support, but perhaps the international spotlight will lead to greater local recognition of the role the arts play in development.

The Jamaica Jamaica! show is being held at the Philharmonie de Paris, a cultural institution at Paris’ immense Cité de la Musique complex. The Philharmonie focuses on music in all its forms and comprises state-of-the-art auditoriums, exhibition spaces, and practise rooms. It had long wanted to host an exhibition about Jamaican music, says Marion Challier, exhibition project manager.

“But we wanted to show the culture as well as the music and to show that Jamaican music is an important part of the history of the Black Atlantic,” she tells IPS. “There are so many stereotypes about the music and so many stigmas attached and we wanted to go beyond that.”

For the organizers, including curator Sébastien Carayol, it was important to show the African roots of the music and to shine a spotlight on its early forms, such as kumina and mento, as well as on ska, rocksteady, reggae and dancehall. “It was essential for us that the exhibition wasn’t just about Bob Marley,” Challier says.

Items about Jamaica’s most famous musician and his band The Wailers naturally form a significant part of the exhibition, but the show delves into the island’s “complex history” and the role that music has played throughout.

According to the organizers, “The branches of Jamaican music reach as widely as those of jazz or blues, and its roots dig deep into the days of slavery, tracing back to traditional forms of song and dance inherited from the colonisation of the 18th and 19th centuries.”

Still, “what many people don’t know is that since the 1950s, inventions in Jamaican music — born out of the ‘do-it-yourself’ ingenuity pulsing through the ghettos of Kingston — have laid the foundations for most modern-day urban musical genres, giving rise to such fixtures of today’s musical lingo as ‘DJ’, ‘sound system’, ‘remix’, ‘dub’, etc.”

The Philharmonie adds that: “Jamaican music is anything but one-dimensional. Often placed under the heading ‘World Music’, it is so popular around the globe that it could be called the ‘World’s Music.’”

Carayol, the curator, says that a particular interest for him was to show the “legendary sound systems” that have been an intrinsic part of 20th-century Jamaican culture. The exhibition has assembled original “sound-system” speakers dating from the 1950s and 1960s, for instance. Many of these had been discarded, and it was thanks to collectors who “rescued” them that they can now be displayed.

In fact, one huge speaker box was being used as a bench in somebody’s yard when a collector from the United Kingdom spotted it and managed to get it renovated, according to Carayol. It’s currently back in working order.

These sound systems lend themselves to the interactive nature of parts of the exhibition. Visitors are invited, for instance, to take a stint as the “selector,” to spin records, “turn up the volume and feel” their own sound “delivered by a world-class sound system custom built by sonic master Paul Axis.”

In other spaces, visitors get to learn about the famed Alpha Boys School, where orphans or other disadvantaged youth were groomed to become musicians at an institution run by Roman Catholic nuns in Kingston.

The school has had its own band since the 1890s, and its alumni have influenced the development of both ska and reggae, according to historians. The four founding members of the Skatalites group (Tommy McCook, Don Drummond, Johnny “Dizzy” Moore and Lester Sterling) were “Alpha boys,” and the exhibition includes a vibrant mural of the group — painted by Coxson.

“These young men overcame their beginnings and became truly proficient musicians,” says Carayol. “That story is very important to me. It’s a universal story.”

The School will have tee-shirts on sale to raise funds for its continued operation, following fears that it would have to be closed in the future.

Jamaica Jamaica! also includes paintings of personalities often mentioned in reggae lyrics, such as Pan-African leader Marcus Garvey and Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, and visitors can listen to records that mention these political figures.

“Through installation, artwork, recordings, film — we’re trying to explain who everyone is,” says Carayol.

Asked why he, a Frenchman, was the curator of the exhibition, Carayol said the “simple” reason was: “You spend three years writing a project and it has to be written in French.”

Beyond that he has the “interest and the expertise,” he said, having spent years researching and directing films about the music. “The last thing I want is to be an outsider looking in and telling Jamaican people about themselves. I’m here for them to teach us and not the other way around. That’s my main focus,” he told IPS.

For Jamaicans who lived through the turbulent 1970s, an aspect of the exhibition that will strike a particular chord is the connection between the music and politics, and this is presented in a number of ways. There are the songs that came out of that period, the film footage, and iconic photographs of the famed “One Love Peace Concert,” when Marley tried to bring together warring factions aligned with politicians Michael Manley and Edward Seaga.

The so-called “rod of correction” used by then prime minister Manley is on display too. Manley gained support from the island’s Rastafarian community partly by claiming that Haile Selassie had given him this rod, or walking stick. And though that claim was later debunked, the “rod” remains the stuff of legend.

Both Manley and Marley are depicted in artwork throughout the exhibition, in paintings by some of Jamaica’s most celebrated artists, including the late Barrington Watson. Many pieces are on loan from the National Gallery of Jamaica and from private collectors on the island and in the United States and Britain.

“One of the big surprises was learning about the art,” Carayol says. “It’s an evocation of the music, and I want to show these artists to people who don’t know about them.”

The expected 150,000 visitors probably won’t forget Coxson, as his paintings of the island’s musicians and of renowned Jamaican poet Louise Bennett puts these personalities resolutely centre stage.