My grandmother, whom we called “Nana,” always loved children. Many times, she asked me to give her great-grandchildren.

In 2000, the moment finally arrived. But it didn’t seem to matter. Eagerly, tenderly I lay my newborn son in her arms. She sat motionless, her eyes void. No expression whatsoever. I searched her face, desperately hoping to see some sign of joy…of recollection…of understanding. Nothing. Her eyes were vacant. She could not speak. She did not move.

The reason? My nana had Alzheimer’s disease. It was during this visit that I started to contemplate the quality of life and the certainty of death.

Almost 20 years later, as I lead the largest national organization advocating for patient-driven, end-of-life care, the consensus among our supporters is clear: They (and I) see nothing compassionate or patient-driven about how people with dementia die.

The cultural “norm” in the United States is that life — regardless of the quality of that life — is better than death. Traditionally, love means keeping someone alive, not helping him or her die peacefully. We are so afraid of death that we don’t ask our loved ones what they want. This paralyzing fear of life’s final chapter leaves us guessing, guilt-ridden and trapped in the default mode of our medical system — life-extending tests and treatments — even for a loved one hollowed by dementia.

We spoon feed and hydrate people with advanced dementia, even though losing the desire to eat and drink is a natural part of the dying process. We prescribe medical treatments — such as kidney dialysis — even if the person declined this preference in writing when they were capable of making an informed healthcare decision. We marshal every resource to extend life and subject nine out of 10 dementia patients to at least one invasive medical procedure in their last week of life. We don’t merely refuse to let people with dementia die; we do everything possible to keep them alive.

This default mode of our medical system contradicts what most people want. According to a study published by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), many people regard being confused all the time (45 percent) as a fate worse than death.

We are using medicine and human intervention to keep people alive for years — long past when they would naturally die. People should be able to document their desires before they have lost their mental capacity to make informed healthcare decisions and realize a natural death, if that is their preference.

This is different from — and should not be confused with — extending medical aid-in-dying laws in California, Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, Washington and Washington, D.C. to people with dementia. Conflating advance directives instructing care providers not to artificially prolong the person’s dying process and asking for a prescription for medical aid in dying, as opponents of both options have been doing, is irresponsible and misleading.

Six million people have dementia right now. According to a newly released study that number will grow to 15 million by 2060. Absent a miracle cure for dementia, millions more Americans will suffer from this devastating disease in the decades to come. It’s time we establish a new cultural norm about death: one that respects the individual person’s autonomy to decide their fate.

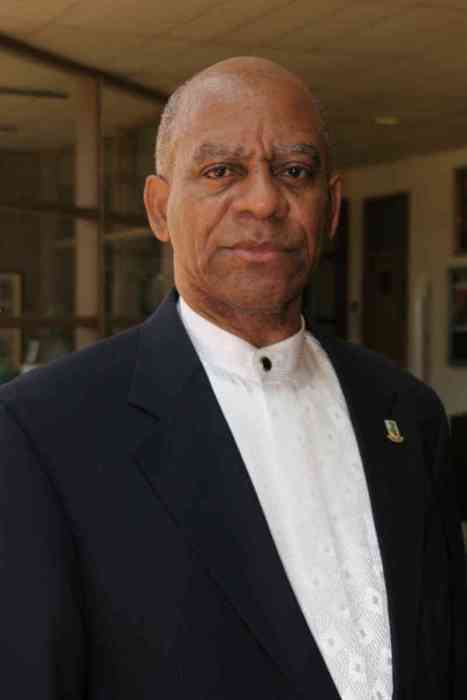

Kim Callinan is the chief executive officer for the Portland-based Compassion & Choices, the largest national organization devoted exclusively to patient-driven, end-of-life care. She has a Master’s degree in public policy from Georgetown University.