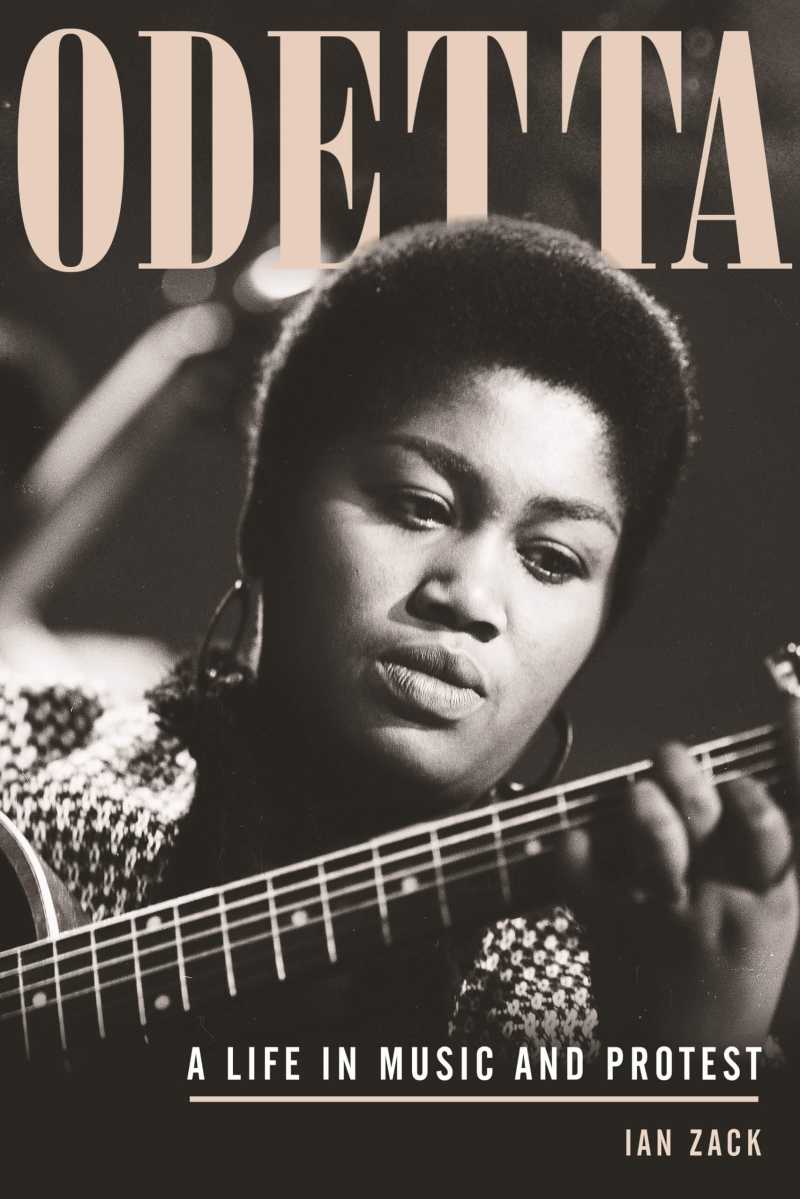

“Odetta: A Life in Music and Protest” by Ian Zack

c.2020, Beacon Press $28.95 / $38.95

Canada 288 pages

The first note had your foot tapping.

It didn’t stop until the set was over or the LP needed flipping. The song moved you; those words meant everything. And the singer of those tunes? She was the entire reason those notes were worth listening to. In the new book “Odetta” by Ian Zack, you’ll find out why so few know her name.

From the time she was old enough to talk, Odetta Holmes could sing.

She was born on New Year’s Eve 1930 to a mother who didn’t want her and a father she didn’t meet until she was in grade school. She was a big girl, and always self-conscious of it; on the day she met her father, he mentioned her size, which embarrassed her enough for the story to carry into her adulthood.

But the big girl had an even bigger talent.

Shortly after her mother remarried and Odetta gained a stepfather and a new surname, money was found for piano lessons. Odetta enjoyed the piano but it was her singing voice that most impressed her teacher, who insisted that the girl have a voice coach. Odetta’s school concurred and she was taught to sing operettas and German lieders, instructions that later served her well – although college was where she learned that music and politics together were a powerful force.

Picking up a borrowed guitar and practicing at hootenannys, Odetta shyly began singing prison songs, spirituals, and then-popular folk tunes and protest songs. As her popularity grew, she became a recording artist, an actor, and a deep inspiration for history’s biggest names and folk music’s best performers, including Paul Simon and Bob Dylan.

Once, she told an interviewer that she didn’t want fame because of the hassle. In the end, Odetta got what she asked for: despite her influential work, she never had a chart-topper or a best-selling record.

The line in the sand could be drawn like this: if you’re a “whatever-music-is-fine” kind of person, then just turn the page. Nothing to see here.

If you consider yourself a major music aficianado and liner-note devotee, though, “Odetta” is your book.

The difference comes in a distinction: Odetta (who professionally used just her first name) never went mainstream despite, as author Ian Zack points out, that her influence peppers music up and down the spectrum over the last forty or fifty years. Casual readers may never have heard of her; Zack shows instead that they’ve heard her through other artists, and it happened in all the wrong ways. Odetta wasn’t a destination, in other words; she was the journey.

Like the life of a not-quite-successful musician, however, “Odetta” struggles. Zack seems to have an odd focus on Odetta’s hair, and the point is overly belabored. There are times, too, when this story drags like back-to-back whole notes, and that’s no fun.

Still, readers who are truly serious about their music will relish “Odetta” as they grab their headphones and an LP to set the mood. If that’s you, consider this book and make note.