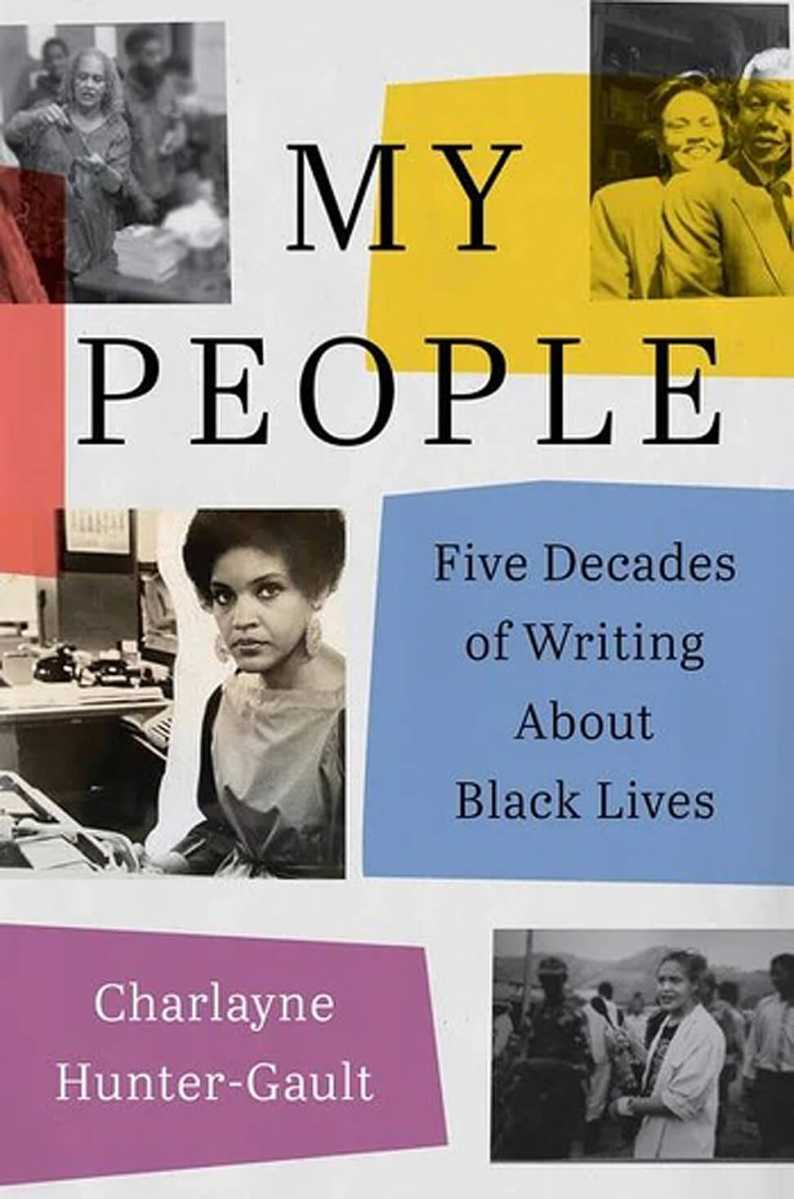

“My People: Five Decades of Writing About Black Lives” by Charlayne Hunter-Gault

c.2022, Harper

$27.99

347 pages

You try to stay on top of things.

You keep your eyes and ears open for news of what’s going on because you know that being informed is being forewarned. Somebody’s got to watch what happens in your state and your city. Somebody needs to keep track of the goings-on in your neighborhood. And in the new book “My People” by Charlayne Hunter-Gault, somebody needs to testify.

It was hot that early July day in 1959 when Charlayne Hunter and a friend went to the Court House in Atlanta to get their college applications certified. That day, they hoped to enroll in the University of Georgia but, though the papers were all in order, the judge refused to sign them, accusing the pair of wanting to cause trouble.

“All this talk made little sense to me,” Hunter-Gault says now.

She’d been “the only Negro” in schools before, so attending the all-white University of Georgia didn’t seem like a big deal. Still, they weren’t accepted – at least not then but a year-and-a-half later, a Federal judge ordered the university to enroll both Hunter and her friend.

That’s not the end of this particular story but a degree in journalism is – and so Hunter (later, Hunter-Gault) went to work reporting the news at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, not long after her own activism.

This book is a collection of some of her columns and interviews.

Perhaps because of her own experiences in education, she writes of schools, integration, and curriculums. She tells tales of other Civil Rights icons, John Lewis, the Panthers, Mandela and Tutu, The Black Women’s Community Development Foundation, Shirley Chisolm. She writes about living and working in South Africa and in Harlem.

Personally, Hunter-Gault writes of her jobs in newspaper and television, what a delight it is to find a good vacation spot, and how to talk to young people about Trump and today’s current events. And she sings the praises of Black newspapers, that “‘tell their story.'”

As memoirs go – and this is a kind of memoir – “My People” is really different.

You have to look quite a bit between the lines to get author Charlayne Hunter-Gault’s story; it’s here, just not presented in the way you expect a life story to be. Instead, Hunter-Gault wraps her experiences inside the things on which she reported in these columns from the middle 1960s to just a few years ago.

What’s interesting is that the columns, despite the age of some of them, seem as fresh as if they were written last year. Hunter-Gault’s work often focused on reporting issues of racism and inequality and the people who fought those things through the years, and yet readers will see the modern relevance. Sadly, however, there’s no editorializing or commentary on that; the columns merely stand on their own.

Still, this collection-cum-memoir is a fascinating read, especially for someone who’s looking for a unique sort of historical record. For you, “My People” is the thing to put at the top of your to-be-read pile.