Tanya came to me for an abortion. She has two children and despite working two jobs, has the means to raise one and is pregnant with a third. She is a resilient woman, but this additional pregnancy is one too many. She feels stigma and shame walking into the abortion clinic, but this is actually more a commentary on our ethics and morality as society than on the “immorality” and shame of Tanya and thousands of American women like her who need abortions.

By failing to provide adequate access to affordable contraception, by failing to offer enough jobs that pay a living wage, by failing to address health disparities, we have failed poor women, many of whom are women of color. They come to me to take care of the pregnancy, so they can find a better paying job, finish their education or training, and try to scrape by and hopefully scrape up a better life for themselves and for the children they often already have.

I see women who have abortions for many reasons. Some are straightforward like after a rape, a contraceptive failure or in the case of a severe fetal anomaly. Others are due to a confluence of factors. While abortion is not an economic decision, sometimes there are economic factors.

Women need access to safe and legal abortion. Only this health service has become marginalized in our health care system. It is singled out from other health services in the way it is treated in both public and private insurance systems. Increasingly, it is subject to “safety” restrictions that have nothing to do with the health and safety of women who need the service and everything to do with restricting access to abortion. By limiting the supply without addressing the needs that drive the demand, we are denying women access to safe health care in their darkest hours.

Abortion is at its root a public health and safety issue. Strikingly, the numbers of abortions were fairly constant pre – and post- the Roe v. Wade decision, at roughly one million per year. The difference legality has made is in safety, for all women and especially for poor women of color. Pre-Roe, middle class and wealthy women could usually find a doctor who would walk them through the hospital’s review board process and help them make their case for mental health or other dispensation. It was often poor women, many of whom were women of color, who were driven to the clandestine back alley abortionists, at risk to their health and even their lives. It is estimated that about 5,000 U.S. women died per year pre-legalization in the years leading up to the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision.

Today, 88 percent of abortions are performed in the first 12 weeks when complications are exceedingly rare (.5 percent) and most of the complications that occur can be handled in the physician’s office or clinic. This is the science at work. This is also the humanity we can offer a woman when we have failed to provide the supports she needs that could have prevented the need for this abortion. Our goal should not be to eliminate abortion but to address circumstances—socioeconomic, health access, racial and institutional barriers — that lead a woman to choose abortion, and then to make sure that safe, legal abortion is there as a backup because we are not able to reduce all risk.

Abortion comes from unplanned and unwanted pregnancies, and from wanted but lethally flawed pregnancies. Poor women, young women and women of color are most likely to experience unintended pregnancies. Women with incomes at or below the federal poverty level are five times more likely to have unintended pregnancies than are women at the highest income level. Black women have an unintended pregnancy rate that is more than double that of non-Hispanic white women.

Unplanned pregnancies bring inherent risks. Women may begin late treatment for conditions such as high blood pressure or diabetes which need to be controlled in order to have healthy birth outcomes for women and their infants. Women may unknowingly expose their fetuses to dangerous substances. Women are also less likely to access timely or enough prenatal care.

Black women also have more co-morbidities related to poverty and the harsh realities of living with violence and discrimination. They are also three times more likely to experience death as a result of childbirth than are white women.

Focusing only on the fetus ignores these very real health risks and disparities. We cannot ignore these disparities away. They are part of the environment in which women live, work and often raise their families.

Under the auspices of increasing abortion’s safety, legislatures across the country have passed more than 200 restrictions on abortions in the past four years. In reality, these new laws only create burdensome restrictions on abortion providers because legal, induced abortion is already so safe. Like mandatory waiting periods and forced ultrasounds, their sole purpose is to make abortion harder, even impossible, to get. When practicing in Mississippi, I am forced to lie to women and tell them abortions may cause breast cancer—a lie which has repeatedly been scientifically disproven. Contrary to the Hippocratic oath I took to “do no harm,” I am forced to uphold institutional barriers that harm rather than help my patients.

All of these restrictions have led to this: The latest data available shows that in 2011, 89 percent of U.S. counties lacked an abortion clinic. With the proliferation of new abortion restrictions, there is reason to believe that the number of providers will continue to fall. We are closer than at any time post-Roe to the specter of nowhere to get a safe, legal abortion. That is the real shame.

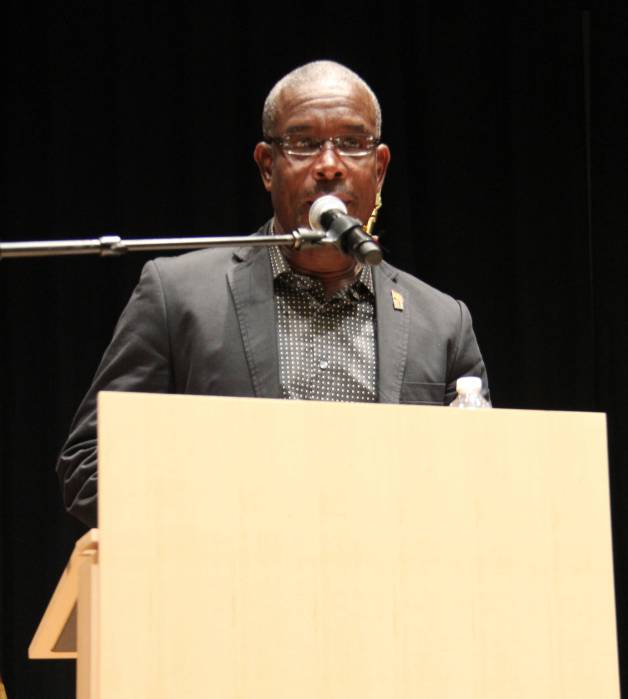

Willie Parker, MD, MPH, MSc, is a physician and reproductive justice advocate and board member, Physicians for Reproductive Health