The absence of up-to-date poverty and inequality data in the Caribbean leaves thousands, if not millions, unseen and unheard, undermining progress toward improving lives and ending poverty. On the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty, we emphasize the urgent need to measure poverty in order to inform corrective policy measures, ensuring that no one in the Caribbean is left behind.

The Data Gap

In the Caribbean, understanding poverty and exactly who is affected and how, in order to inform corrective policy measures, is inhibited by the absence of data. Many Caribbean countries simply do not collect the data to measure and monitor poverty and inequality.

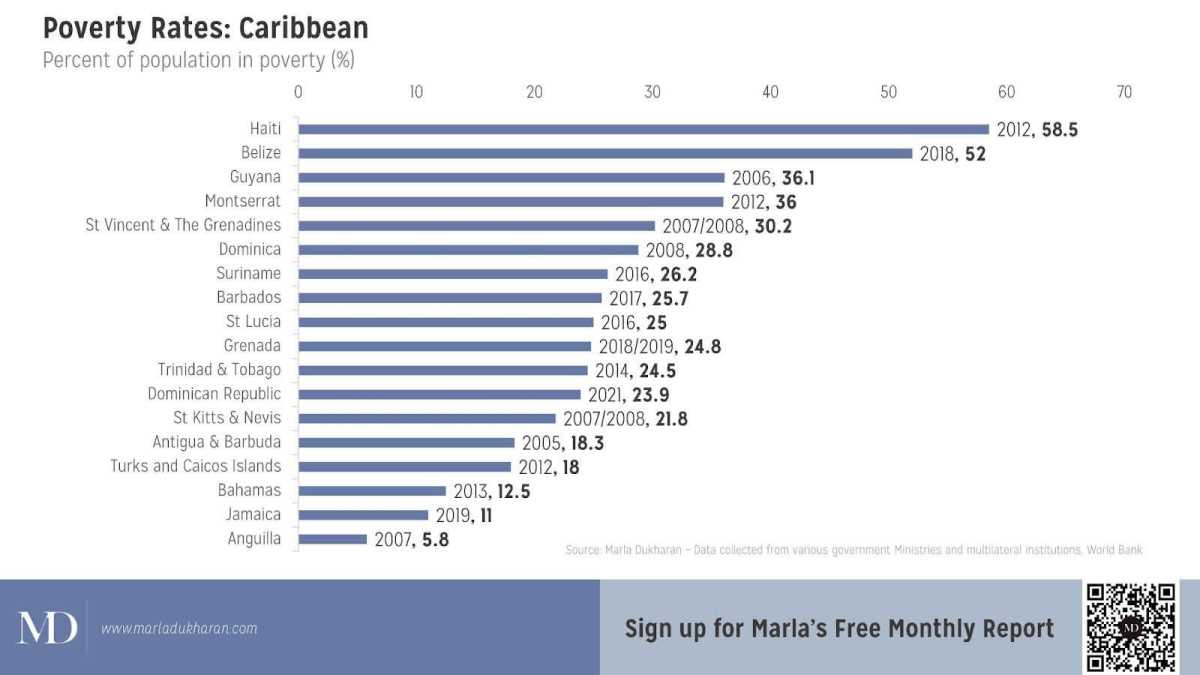

A World Bank study carried out in 2015 showed that nine Caribbean countries were data deprived, meaning they had one or less poverty estimates available within a 10-year period. The recommended frequency is 3-5 years (see chart showing the latest poverty data available by country).

This situation has not changed much since 2015. In 6 out of 18 countries in the Caribbean, national poverty estimates are available only for the 2000s. With the exception of Jamaica, which has a long history of monitoring poverty on an annual basis, and the Dominican Republic, the most recent poverty estimates are between 5 and 7 years old. In several countries, socio-economic information such as unemployment rates and demographic characteristics, is also not collected regularly.

Unless we have up-to-date poverty data, we are unable to measure progress toward poverty reduction and may in fact be heading toward higher levels of poverty and inequality. Without the data, we are also unable to develop effective policies and interventions that address poverty, and social welfare spending could end up missing the mark completely.

Caribbean people suffered severe socio-economic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic and their households were hit by yet another shock when living costs increased sharply in 2022. Evidence from phone- and online-based surveys conducted by development partners in recent years suggests that these shocks hit the poor and vulnerable the most, leading to rising inequality which is very visible now and a direct cause of poverty as the two reinforce each other in a vicious cycle.

The CARICOM Food Security & Livelihoods Impact Survey showed that, when faced with rising food prices in 2022, low-income households in the Caribbean were much more likely to reduce essential expenditure in health and education or sell productive assets to meet food needs than those better-off. Such coping behaviors reinforce inequality. On the other hand, higher levels of inequality can perpetuate poverty if power is concentrated in the hands of a few and limits access to opportunities or basic needs for those who need it the most. We need the data, and we need deliberate policy action to break this cycle so many are stuck in.

More frequent household data can also be used to improve our resilience to climate change and natural hazards, for instance, by combining household data with climate and hazard data for vulnerability assessments that can inform targeted policies.

In the context of higher debt levels, the absence of recent poverty data means poverty may be less of a policy priority, but when poverty policies are implemented without sound data and evidence, they are less likely to be successful, resulting in wasted resources. The Caribbean simply can’t afford to continue along this path – Caribbean people deserve better.

The Capacity Gap

Statistical capacity in the Caribbean is lower than in other world regions globally, as measured by the Statistical Performance Indicator. Many Caribbean countries struggle with weak statistical capacity and low data usage, which reinforce each other.

Limited capacity means that the quality of the data can be poor and outdated. In addition, countries sometimes opt not to disclose poverty data based on political sensitivities, which hampers policymaking to improve the lives of the most vulnerable.

What Can Be Done?

Some Caribbean countries have made efforts to address aspects of the data gap. For example, initiatives like the World Bank funded OECS Data for Decision Making Project, the Caribbean Development Bank’s Enhanced Country Poverty Assessment Project or Statistics Canada’s Project for the Regional Advancement of Statistics in the Caribbean have been implemented with the support of development partners. However, if we are to end poverty by 2030, the following needs to be considered:

- Commit to regular and comprehensive data collection on poverty and key socio-economic indicators. This includes conducting household surveys, censuses, and surveys to gather information on income, living conditions, employment, education, and healthcare access. Governments must budget appropriately to conduct these surveys, and the development community can support these efforts by providing additional funding, capacity building and analytical support.

- Invest in the capacity of national statistical offices and policy analysis units. This includes adequate staffing of statistical offices and providing training and resources to staff responsible for data collection, analysis, and reporting.

- Promote data transparency and accessibility. This includes making key indicators of surveys and poverty estimates available online and through public events, strengthening the legal framework for microdata dissemination and investing in microdata repositories for safe storage and dissemination.

Conclusion

Poverty projections conducted for the Caribbean by the World Bank and, insights from phone and online surveys conducted during the pandemic suggest that the Caribbean may not be making material progress with poverty reduction.

Although poverty is expected to be on a declining path since its spike in 2020, in most countries it is believed to still be above pre-pandemic levels. There is much work to do to help the poor and vulnerable recover from the pandemic and ensure that there will be no long-term impacts on the welfare of future generations who suffered from severe disruptions in education and health services during the pandemic. It is now imperative that leaders, in collaboration with international organizations and civil society, seize this opportunity to collect and transform data into meaningful action, leaving no one behind.

At an individual level, we all need to advocate for governments to conduct and share assessments of poverty and the corresponding outcomes. By advocating for greater openness and transparency, we can contribute to the reduction of poverty and improved Caribbean lives and livelihoods.

Lilia Burunciuc is the World Bank Director for Caribbean countries and Marla Dukharan is recognized as a top Caribbean economist.