HAVANA, Jan 16 2015 (IPS) – On Dec. 17, by freeing the five Cuban anti-terrorists who spent over 16 years in U.S. prisons, President Barack Obama repaired a longstanding injustice while changing the course of history.

Admitting that the U.S. government’s anti-Cuba policy had failed, reestablishing diplomatic ties, lifting all of the restrictions within his reach, proposing the complete elimination of the embargo and launching a new era in relations with Cuba, all in one single speech, went beyond anyone’s predictions and took everyone by surprise, even the most seasoned analysts.

The hostile policy first adopted by President Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953-1961), before the current president was even born, was followed with only slight variations by Republican and Democratic administrations, and codified by the Helms-Burton Act signed into law by President Bill Clinton in 1996.

In the first few years the policy was practiced with a high degree of success. In 1959, when the Cuban revolution triumphed, the United States was at the height of its power, exercising indisputable hegemony over a large part of the world, especially the Western Hemisphere, which enabled it to get Cuba kicked out of the Organisation of American States (OAS) and to achieve the near total isolation of this Caribbean island nation, which was left with only the support and aid of the Soviet Union and its partners in the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA), which grouped the countries of the Warsaw Pact.

The collapse of real socialism gave rise to hopes among many people that the end of the Cuban revolution was also at hand.

They imagined the advent of a long period of unipolar dominance. Drunk on the victory, they failed to appreciate the deeper meaning of what had happened: the end of the Cold War opened up new possibilities for social struggles and faced capitalism with challenges that were increasingly difficult to tackle.

The fall of the Berlin Wall blinded them from seeing that a social uprising known as the “Caracazo”, which shook Venezuela at the same time, in February 1989, was a sign of the start of a new age in Latin America.

Cuba managed to survive the disappearance of its long-time allies, and its ability to do so was a key factor in the profound transformation of the region. For years it had been clear that the U.S. policy aimed at isolating Cuba had been a failure, and had ended up isolating the United States, as acknowledged by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry.

A new relationship with Cuba was indispensable for Washington, which needed to rebuild its ties with a region that is no longer its backyard. Achieving that is fundamental now because, despite its power, the United States cannot exercise the comfortable leadership of times that will not return.

But there is still a long way to go before that new relationship can be established. First of all, it is necessary to completely eliminate the economic, trade and financial embargo, as demanded with renewed vigor by major segments of the U.S. business community.

But normalising relations would suppose, above all, learning to live with differences and abandoning old dreams of domination. It would mean respecting the sovereign equality of states, a fundamental principle of the United Nations Charter, which, as history has shown, does not always please the powerful.

With regard to the release of the five Cuban prisoners, all U.S. presidents, without exception, have broadly used the authority granted to them by article 2, section 2, clause 1 of the U.S. constitution. For over two centuries, presidents have had the unlimited power to grant reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States.

In the case of “the Cuban Five,” there were ample reasons for executive clemency. In 2005, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals overturned the trial as “a perfect storm of prejudice and hostility” and ordered a new trial.

In 2009 the same court threw out the sentences against three of the Cuban Five because they had neither sought nor passed on any military secrets, nor had they endangered U.S. national security.

Both verdicts were unanimous.

With respect to another major charge, “conspiracy to commit murder,” against Gerardo Hernández Nordelo, his accusers admitted that it was impossible to prove such an allegation, and even attempted to drop the charge in May 2001 in a move without precedent, made no less by public prosecutors under then-President George W. Bush (2001-2009).

Hernández had been waiting for five years for a response to one of his many petitions to the Miami court for release, a review of his case, an order for the government to produce the “proof” used to convict him, or for the government to reveal the magnitude and scope of official funding for the colossal media campaign that fed the “perfect storm.”

The court never responded. Nor did the mainstream media say anything about the judicial system’s unusual paralysis. It was obvious that it was a politically motivated case that could only be resolved by a political decision, which only the president could take.

Obama demonstrated wisdom and determination when, instead of simply using his authority to release the prisoners, he bravely confronted the underlying problem. The saga of the “Cuban Five” was the consequence of an aggressive strategy, and the wisest thing was to put an end to both at the same time.

No one can deny the importance of what was announced on Dec. 17. It would be a mistake, however, to ignore that there is still a ways to go, and that it will be necessary to follow that possibly long and tortuous path with resolution and insight.

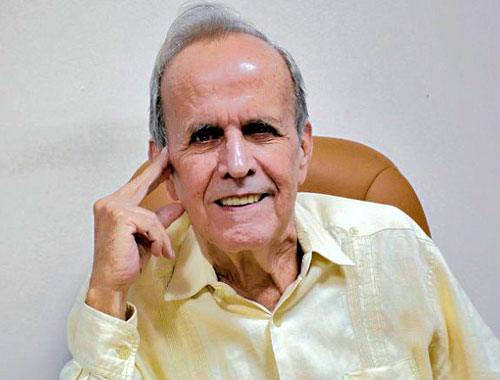

Ricardo Alarcón is a former Cuban foreign minister and president of parliament.

Edited by Pablo Piacentini/Translated by Stephanie Wildes

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, IPS – Inter Press Service.