– With the unprecedented ageing of populations worldwide, countries are struggling with the critical questions of who should be responsible for caring for the old and what should be the extent of care provided to women and men in old age.

Many believe that the government should be responsible for covering the costs and providing care, support and assistance to the old. In contrast, others, in particular social conservatives, contend that families and the old themselves should be responsible for providing the needed care, support and assistance for the old.

Similarly with respect to the extent of care to be provided to the old, some argue that given the high costs, the demands involved and the appropriate role of government in family life, only rudimentary care should be made available to the old in need. Others, however, believe that government should provide a broad array of services and care to the old, especially for those with special needs and disabilities.

For many countries the issue of caring for the old is the single most expensive domestic priority today and is expected to remain so in the years ahead. In addition to the substantial financial costs, governments are wrestling with contentious policy issues, including competing national priorities, the proper role of government and the responsibilities of individuals for their personal wellbeing in old age.

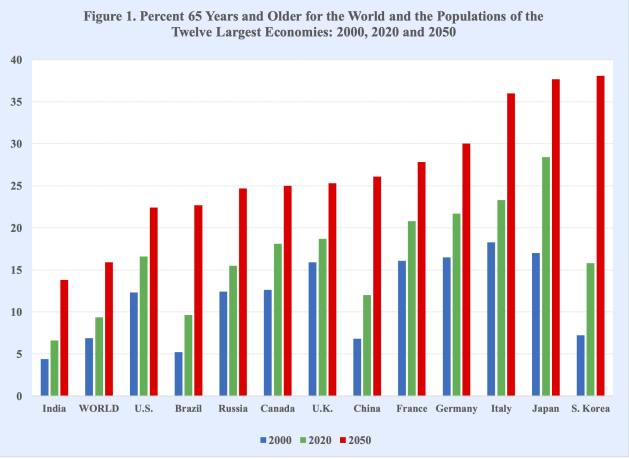

The significant increases in the proportions elderly that occurred during the past two decades are expected to continue throughout the 21st century. Among the populations of the 12 largest economies, for example, which account for approximately 70 percent of the world economy and 50 percent of the world’s population, the proportions 65 years and older have increased markedly since the start of the 21st century (Figure 1).

In China, for example, the proportion aged 65 years and older nearly doubled in the recent past, increasing from less than 7 percent in 2000 to 12 percent in 2020. That proportion is expected to more than double by 2050, reaching 26 percent. Similarly, South Korea’s proportion elderly jumped from 7 percent in 2000 to 16 percent in 2020 and is expected to reach nearly 40 percent by 2050, with Japan and Italy close behind at approximately 38 percent elderly.

In addition to the growing proportions of the old, men and women are living longer than ever before. Since World War II remarkable achievements have been made in reducing mortality rates and increasing the length of human lives worldwide.

Over the past seven decades the world’s average life expectancy at birth has increased 26 years, from 47 to 73 years. The gains in life expectancy at birth over that period have been even greater, exceeding 33 years, in many developing countries, including Bangladesh, China, Ethiopia, India, Iran, Oman, Peru, Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Turkey.

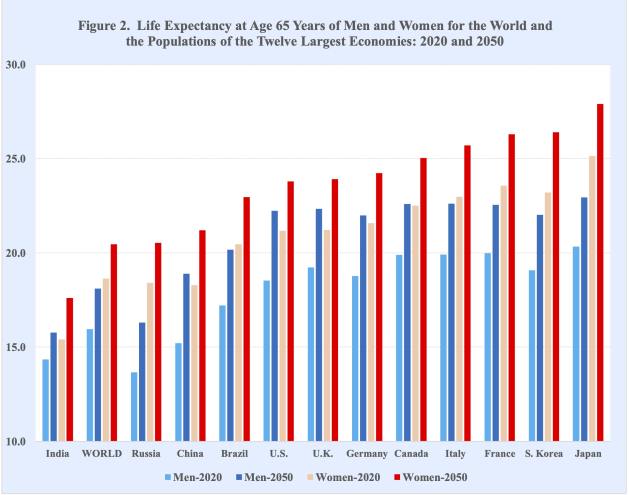

The reductions in mortality rates are also providing additional years of life for the old. For example, by midcentury average life expectancies at age 65 among most of the populations of the 12 largest economies are expected to be no less than 20 years for men and no less 23 years for women (Figure 2).

Particularly noteworthy are the projected life expectancies of elderly women in France, Italy, Japan and South Korea in 2050. In those countries, women on average can expect to live well into their nineties by midcentury.

Human longevity is also reaching record levels. The numbers reaching age 100 years, for example, have grown markedly over the recent past. Worldwide the number of centenarians increased nearly four-fold since the start of the 21st century and is expected to increase nearly eight-fold by midcentury, reaching close to 5 million.

Among the populations of the twelve largest economies, the numbers of centenarians are projected to more than quadruple by 2050. The numbers of centenarians in Brazil and China, for example, are expected to increase eight-fold over the coming three decades.

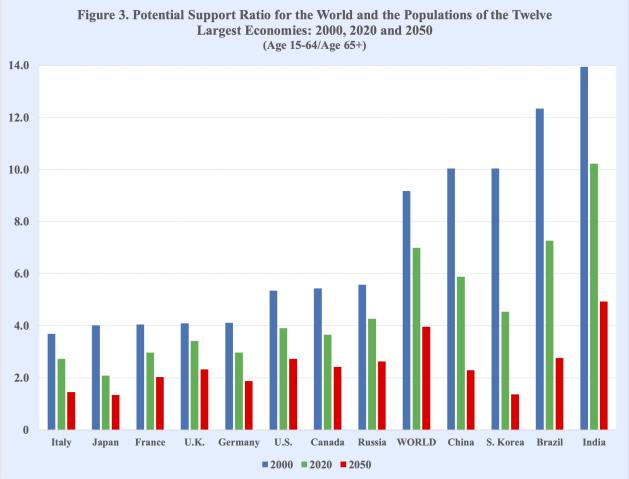

Also importantly, the ageing of populations is also resulting in a declining ratio of tax-paying workers to retirees. The potential support ratio (PSR), or the ratio of working-age persons aged 15 to 64 per one person aged 65 years and older, is declining rapidly with important consequences for decision-making, resource allocations and societal wellbeing.

At the global level, the PSR declined from nine persons in the working-ages per person aged 65 years and older at the start of the century to 7 in 2020 and is projected to decline further to four by midcentury. Also, by the year 2050 some countries, including China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, South Korea and the United Kingdom, are expected to have PSRs of approximately two persons or less in the working-ages for each person aged 65 and older (Figure 3).

Due to demographic pressures of growing elderly populations and the relative decline of workers paying taxes, governments are increasingly facing the need to adjust budgetary expenditures. Some political leaders advocate less spending on domestic programs and entitlements for the old and shifting more of the costs for support, caregiving and services to the old and their families, which they maintain has been successfully practiced by societies throughout much of the past.

Others, however, call for a readjustment of government expenditures including less spending on costly programs, including defense, and increased spending on the rising demands for services, support and care for the old. Increasing taxes on the wealthy, they argue, could make additional funding available for caring for the old.

Encountering increasing difficulties caring for the old, some governments, including China, India and the United States, have promoted and legislated filial obligations for elderly parents. In China, for example, Article 47 of the constitution states that adult children have the duty to support and assist their parents. Also, China passed a law nearly a decade ago requiring people to visit or keep in touch with their elderly parents or risk being sued.

Also in India, the government passed the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act in 2007, permitting needy elderly parents to seek monthly maintenance assistance from their children. In the United States, requiring children to care and provide support for their elderly parents is a state-by-state issue, with approximately half the states having filial responsibility laws.

The 21st century is one of unprecedented population aging. The increasing numbers and proportions of the old, who are living longer than ever before, are occurring with simultaneous declines in tax-paying workers who finance programs for the old in many countries.

The ageing of populations is challenging the viability of government pension systems and healthcare programs for the old. In addition, the demographic changes are increasing stress, anxiety and burdens on families, many of whom are struggling to find the resources, time and means to care for elderly family members.

Caring for the old can be particularly burdensome for women, who have traditionally provided care and assistance to elderly family members yet received limited compensation or recognition for their efforts. While many find providing care to the old emotionally rewarding, the work can be burdensome, interrupt employment and careers and harm the economic and personal well-being of caregivers.

In sum, caring for the old will increasingly be a mounting challenge for governments, communities and families throughout the 21st century. Among the central aspects of that challenge are who should be responsible for providing care for the old and what should be the nature and extent of the care to be provided to the old.

Ignoring or postponing addressing the consequences of population ageing is the typical response of governments when confronting relatively slow-moving, momentous demographic trends. Doing so, however, will only intensify the formidable challenge of caring for the old.

Joseph Chamie is a consulting demographer, a former director of the United Nations Population Division and author of numerous publications on population issues, including his recent book, “Births, Deaths, Migrations and Other Important Population Matters.”