A recent Caribbean Court of Justice ruling has re-enforced the fact that a passport issued by any of the 15 member states of CARICOM is considered superior to that of the US as a travel document within this region.

This unusual state of affairs in which passports of tiny third World or Developing countries carry a higher ranking than that of the powerful United States was made clear when a Grenadian national, who is also an American citizen, opted to use his US passport to enter Trinidad and Tobago instead the document from the land of his birth, and was rejected.

Contending that he had been denied his right to free movement as a CARICOM citizen the Grenadian, David Bain, took the matter to the CCJ.

But this court, which holds final jurisdiction over matters of all CARICOM agreements, ruled that the “onus lies upon an intended entrant into a CARICOM Member State to establish that he or she is a national of such a state with the right to freedom of movement”.

In dismissing the claim on May 29, the CCJ indicated that it also relied on submissions from the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) which stated that the “appropriate travel document to invoke the right of freedom of movement is the CARICOM passport or a passport issued by a CARICOM Member State”.

The CCJ concluded that all the documents Bain presented did not conclusively establish his Grenadian nationality.

Freedom of movement of CARICOM citizens under the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas entitles nationals entry and an automatic six months stay in any territory with the option of extending that time. This is unless they have a criminal record or possess no proof of an ability to financially sustain themselves during the stay.

That same CCJ made clear these enforceable conditions in 2013 when it ruled that Barbados immigration officers had violated the rights of Jamaican Shanique Myrie in 2011 by subjecting her to a cavity search, locking her up, then deporting the CARICOM visitor contrary to Treaty rules.

At time the court had ordered Barbados to pay Myrie a sum of money for damages, plus pay her attorney costs.

In December 2017 when Bain had sought entry into Trinidad’s Piarco International Airport as an American proffering his US passport, he explained that his Grenadian documentation had expired some years ago.

But Trinidad authorities said they found similarity of Bain’s name to that of a person with criminal convictions relating to illegal drugs.

In spite of the Grenadian offering his island’s driver’s licence and voter registration card as supplementary identification the Trinidadian immigration officers denied him entry.

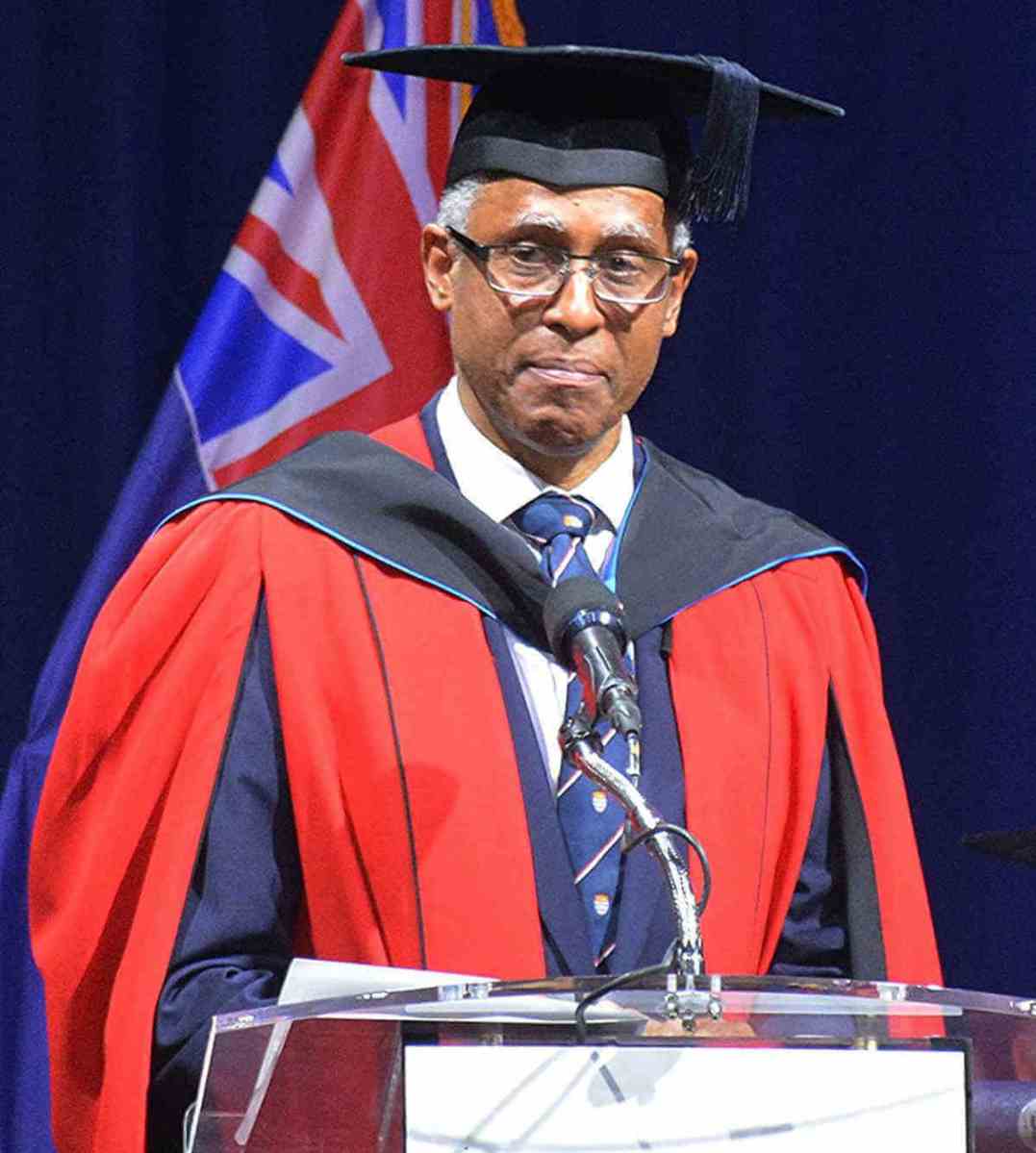

In the decision made by Justices Adrian Saunders, CCJ President; and Jacob Wit, David Hayton, Winston Anderson and Andrew Burgess the Court reported it determined that, while there was no doubt that Bain is a Grenadian citizen, he did not present sufficient documentation to prove it to the immigration officers.

According to the CCJ, the presentation of the Grenadian driver’s licence and voter’s identification card was not sufficient. Unlike the Grenadian passport, neither document was meant to serve as evidence of citizenship. In addition, they were neither machine readable nor designed to be stamped by immigration officials.

This ruling holds lessons for members of the Caribbean diaspora who may be visiting a CARICOM jurisdiction outside the one of their birth because without their home country’s regional passport, rights of entry and stay are restricted.