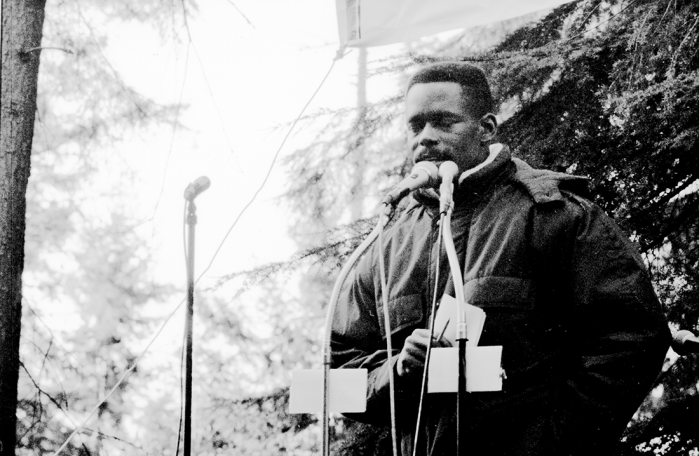

CHARLES TOWN, Jamaica (AP) — In a backwoods town along a river cutting between green mountains, quick-footed men and women spin and stomp to the beat of drums. One dancer waving a knife is wrapped head-to-foot in leafy branches, his flashing eyes barely visible through the camouflage.

This traditional dance re-enacts the Jamaican Maroons’ specialty: the ambush. It was once a secret ritual of the fierce bands of escaped slaves who won freedom by launching raids on planters’ estates and repelling invasions of their forest havens with a mastery of guerrilla warfare.

But on this day, descendants of those 18th century fugitives are performing for tourists, academics, filmmakers and other curious outsiders in a fenced “Asafu” dancing yard in Charles Town, a once-moribund Maroon settlement in eastern Jamaica that seemed destined to lose its traditions until revivalists gradually brought it back.

Maroons in the Caribbean are increasingly showcasing their unique culture for visitors in hopes that heritage tourism will guarantee jobs for the young generation and preserve what remains of their centuries-old practices in mostly remote settlements. The basic idea has been tried around the world, from the Gusii people of Kenya to the artisans of the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina.

“If we don’t follow in the footsteps of our foreparents we will find ourselves on the heap of history,” said Wallace Sterling, the “colonel” of the Windward Maroon community of Moore Town. It is one of Jamaica’s four semi-autonomous Maroon tracts, each governed by an elected colonel, a title bestowed on Maroon leaders since their battles with the British army, and a council appointed by the leader.

Trying to counter the endless tide of migration and assimilation, long secretive Maroons are more and more going public with the old ways — singing sacred songs, drumming, making herbal medicine, talking to ancestral spirits, woodcarving, hunting and “jerking” wild pigs. Maroons are credited with inventing Jamaica’s “jerk” style of cooking, in which aromatic spices are rubbed or stuffed into meat before it is roasted on an open fire.

The turn to small-scale tourism for income can safeguard the Maroons’ future and their cultural identity, leaders say. They say it has boosted pride among younger Maroons and encouraged some to stay in their rural hometowns. Other money-making opportunities are scarce in the communities of modest cement-block homes and tiny shops selling cold drinks and snacks.

“For a long time, it’s been very difficult to keep the young people because they tend to leave for the cities to seek work. But now we can train tour guides and our people can sell their crafts, their banana and coconuts,” said Fearon Williams, the colonel of Accompong. An annual Jan. 6 celebration draws thousands of visitors to the isolated town, which sits among rocky cliffs and limestone towers in northwestern Jamaica. “Tourism is making us stronger.”

A tour bus now comes weekly to Charles Town, a village whose colonel, Frank Lumsden, worked as a commodities trader in Chicago before returning to Jamaica in the late 1990s to focus on his ancestral roots.

There are also Maroons in Suriname, on the South American mainland, where escaped slaves over the centuries built their own African-centered societies in sparsely populated Amazonian forests. Suriname’s Maroons also say a broadening emphasis on ecotourism is helping fight cultural disintegration.

“The world is turning into one large village, so it makes no sense for Maroon villages to keep out tourists. Tourists and the money they bring stimulate people in the Maroon communities to produce the products that represent their culture,” said Ronny Asabina, a Maroon who serves in Suriname’s legislature.

But most acknowledge the obstacles facing Maroons, who are estimated to number in the thousands in Jamaica and the tens of thousands in Suriname. The passing along of traditions and customs from one generation to the next has long been weakened by the lures and necessities of modern life.

In Scott’s Hall, a subsistence farming community in eastern Jamaica, longtime colonel Noel Prehay said he hopes tourism can provide a place for many of his townspeople to relearn their traditions.

Prehay said devotion to clandestine spiritual rituals is strong among the town’s ever-dwindling number of elderly residents, as is their knowledge of the Maroon’s Kromanti language, which is closely related to the Twi spoken in parts of the West African nation of Ghana.

“If a person is mad or if they are sick, we can make a healing dance. Our Obeah is a good Obeah,” Prehay said, referring to an Afro-Caribbean religion that involves channeling spiritual forces and is feared by some in Jamaica’s countryside, where superstitions about shamanism and the occult run deep.

But visitors are very rare in his poor town along a dusty, rutted road about a 45-minute drive from Jamaica’s capital, Kingston. Unlike the other three Maroon communities in Jamaica, Scott’s Hall has no museum, dancing grounds or other attractions aimed at tourists.

So Prehay worries that most young Maroons will still continue to leave.

“I think the young people are willing and ready to accept the teaching of the culture. But the continual migration to Kingston, to London, to Canada is difficult,” the 70-year-old Prehay said, pointing to surrounding slopes that were farms when he was a young man but are now overgrown with bamboo.

Settlements of escaped slaves emerged in many places in the Western Hemisphere, including the U.S., but the Maroons’ biggest success came in Jamaica, where they helped the British expel the Spanish and then turned on the new rulers, wreaking havoc across an island that was then one of the world’s largest sugar producers.

The Maroons’ name derives from the Spanish word “cimarron,” which means “untamed” or “the wild ones.” Descendants of the warrior Ashanti and Fante tribes of West Africa, the Maroons became adept at surviving in tangled forests in the mountains.

Jamaica’s Maroons avoided open warfare, relying on their knowledge of the terrain, camouflaging themselves with leaves and communicating with the abeng, a cow horn whose call carries for miles.

After nearly a century of fighting, the British finally granted the Maroons formal freedom in a 1739 treaty signed in a cave a few miles outside Accompong by legendary Maroon leader Cudjoe and British army Col. John Guthrie.

But in return for their autonomy, the Maroons agreed to help the British hunt down future runaway slaves. That arrangement may be at the root of a sense of isolation some Maroons felt from other Jamaicans and long kept them living apart. Maroon separatism began to fade with the ebbing of colonialism in Jamaica, which became independent in 1962.

Not all Maroons are confident that relying on tourism can successfully bring back cultural traditions.

“It will take a giant effort if you can find the will. I am not sure that the will is there,” said C.L.G. Harris, a highly respected 95-year-old who was Moore Town’s colonel for decades and worked hard to modernize the community — sometimes, he says, at the expense of traditional religious practices.

Anthropologist Kenneth Bilby, whose book “True-Born Maroons” is based on years of research, much of it conducted while living in Moore Town in the 1970s, said it remains to be seen whether heritage tourism can preserve indigenous communities.

“It’s really quite a complex question whether or not communities can try to develop aspects of their culture and commodify them without also suffering certain losses or negative consequences,” Bilby said from his home in Colorado. Some experts fear that cultural tourism can introduce harmful influences or can make communities into parodies of themselves.

Still, the message of cultural identity is reaching some young Maroons.

“What I’ve learned is that without the culture, you’re nothing,” said Rodney Rose, Charles Town’s 29-year-old abeng blower and museum treasurer who until recently had to travel outside the village for employment. “And while we young Maroons are learning, people from overseas can also learn.”

AP Photo/David McFadden