Caribbean diplomats in London have asked the United Kingdom (UK) government to be more compassionate in the treatment of Caribbean nationals

The diplomats on Wednesday urged the British Home Office to adopt this approach towards retirement-age Commonwealth citizens facing deportation, despite living in the UK all their adult lives, according to the British Guardian.

The paper said there could be thousands of people born in Commonwealth countries who emigrated to the UK with their parents as children and did not realize they were required to formally naturalize in Britain.

Their unresolved residency status could mean they face problems accessing pensions, housing, healthcare and work, said Guy Hewitt, the Barbados high commissioner in London.

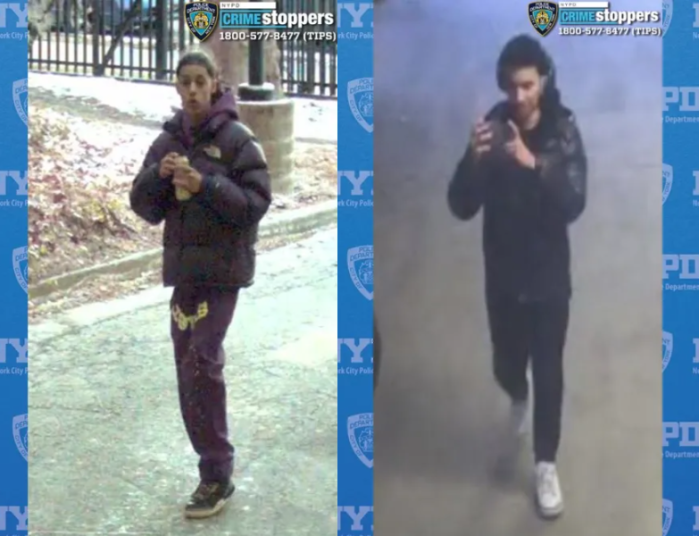

New evidence of harsh treatment by the Home Office emerged this week when officials said they “now accepted” that Anthony Bryan, 60, who has spent five weeks in immigration detention centers in England, was in fact “lawfully present in the UK”.

Bryan, a grandfather who has lived in the UK for 52 years, has had two spells in detention and was booked last November on a flight to Jamaica, a country he left in 1965, when he was eight, and has not visited since, the Guardian reported.

It said the decorator lost his job in 2015 because he was unable to prove he was not an “illegal worker”, and struggled to convince the Home Office of his right to be in the UK until his case was highlighted in news reports last year.

Bryan said he was relieved but angry at his treatment, which has left him heavily in debt because he was prevented from working for almost three years, according to the Guardian.

“I told them I was eight years old when I arrived here, but nobody believed; they told me I was an illegal immigrant and a criminal. They locked me up unlawfully. It was very stressful. It has been a nightmare,” he said.

Hewitt and fellow high commissioners have raised the broader issue with the Foreign Office, urging officials to take a more humane approach in cases like Bryan’s and Paulette Wilson’s, a grandmother who lived and worked in the UK for 51 years, having arrived aged 10, before being told she was an illegal immigrant, being detained and threatened with forced removal to Jamaica, the Guardian said.

It said Caribbean diplomats were concerned people were reluctant to try to regularize their status because of fears they might be detained or deported.

Hewitt described the difficulties experienced by many as a tragedy.

“This is affecting people who came and gave a lifetime of service at a time when the UK was calling for workers and migrants,” he said. “They came because they were encouraged to come here to help build post-World War II Britain and build it into the multicultural place that it is now.

“These are not people who tried to take advantage of the system,” he added. “We need to find a compassionate mechanism for resolving this.”

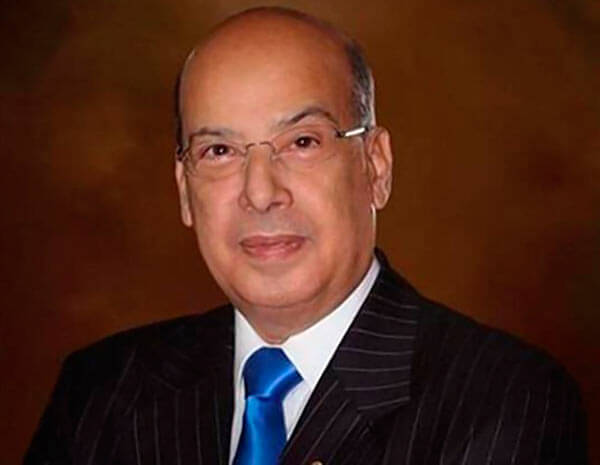

The Jamaican High Commissioner to London, Seth George Ramocan, agreed, according to the Guardian.

“In this system, one is guilty before proven innocent, rather than the other way around,” he said.

Since reports on the situation faced by Bryan and Wilson, the Guardian said Members of Parliament, lawyers and advice centers have highlighted numerous similar cases.

Some people have become homeless as a result of the difficulties they have faced in proving their right to remain in the UK, the paper said.

Diplomats from former Commonwealth countries have organized outreach meetings in areas where there were high levels of immigration from the Caribbean in the 1950s and 60s to inform people about the requirement to naturalize, the Guardian said.

It said many are unaware of the need to regularize their status, partly because they were children when they arrived and also because the rules were less stringent then.

The burden of proving that residency predates the 1971 Immigration Act is on the individual, and it is often hard to gather a detailed paper trail showing school and employment records, the Guardian said.

“These are not people who are seeking to be illegal. They came to contribute to the wellbeing of the UK,” Ramocan said. “It would be in the best interest of all for there to be a more compassionate approach.”

Usually, entry documents to the UK were marked with permanent right to reside stamps, but children were often included on other people’s passports, or have lost their documents, the Guardian said.

A Home Office spokesperson said: “Those who have resided in the UK for an extended period but feel they may not have the correct documentation confirming their leave to remain should take legal advice and submit the appropriate application with correct documentation, so we can progress the case.

“Where the Home Office requires evidence of a person’s residency, the onus is on the applicant to be able to provide this proof,” the spokesperson insisted.

But Hewitt said it was difficult for vulnerable, elderly residents to bring together the required evidence.

“It is really for many a very traumatic process,” he said. “Often, the family and friends who could vouch for them are dead.”