My home state of South Carolina has imposed a tough new law to address “illegal” immigration. Like many recently enacted state immigration laws – which bear a curious similarity from state to state – South Carolina now requires law enforcement officers to check the backgrounds of those they suspect may be in the country illegally, makes it a crime to harbor or transport illegal immigrants, requires immigrants to carry Federal registration documents at all times and requires employers to verify the legal status of all new employees. South Carolina’s immigration law also, however, provides legal status verification exemptions for agricultural laborers, private residence domestic workers, ministers and fishermen on crews with 10 or more hands.

Those exemptions, with the exception of the one provided for ministers, are perfectly understandable to me. I’m a lifelong resident of the state that started the Civil War to defend an economic system based on slavery, designed urban public transit systems to get domestic workers to their employers’ homes, constitutionally mandates a “minimally adequate” public education and recently enacted a Voter ID law to combat “voter fraud,” although there’s scant evidence of voter fraud in our state.

Those exemptions accomplish two things familiar to those who know South Carolina’s history. They offer incendiary inspiration to those easily swayed by the politics of fear and division, and they assure that the affluent who need a cheap and ready labor force won’t be unduly inconvenienced. What’s truly frightening is that other states are now in step with South Carolina, which isn’t exactly a sterling example of educational or economic progress.

The immigration laws passed in many states – like Arizona’s SB 1070 currently being considered by the United States Supreme Court – are convenient tools for social control. Like the Jim Crow laws in the early to mid 20th Century American South, the new immigration laws enable some struggling citizens to blame “those people” for their failure to achieve instead of asking hard questions about systemic economic and social inequities. They also enable elected officials who choose not to run on their records or ideas to fan the flames of division for political advantage and prevent honest consideration of what’s best for all Americans.

Some of those laws are already being “tweaked” in ways that speak to their real intent. In Alabama, legislators are struggling with protests from business interests whose low wage workers have fled the state by the thousands and the negative publicity of a German Mercedes executive’s detention for failure to produce his “papers.” In Arizona, the law was revised to make its inherent need for racial profiling less pointed and more palatable. Trying to mask the intent of those laws, however, is like trying to hide a skunk in a perfume factory – things still don’t smell quite right.

The evolving legal history of immigration in the United States is instructive in considering the new wave of state immigration laws. The Naturalization Act of 1790 extended citizenship only to “free white persons.” The Immigration Act of 1924 sought to stem the tide of Southern and Eastern European immigrants. Nation of origin quotas weren’t abolished until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Whether our ancestors arrived on the Mayflower, in the holds of slave ships like the Amistad or in the “steerage” of ocean liners in the early 20th century, the majority of Americans today are the descendants of immigrants. The sad fact is that those whose families have been here for a generation or two are hostile to those seeking new opportunity in America.

If we are to be the world’s self-professed “melting pot,” then we can’t put the lid on the pot when it comes to admitting those who don’t look like or don’t worship or think in ways acceptable to us. I hope that the Supreme Court will remember that when considering the constitutionality of the latest wave of immigration laws so that we can address 21st century immigration realities, pave the way for new Americans to pursue the American dream and focus on building new American bridges instead of erecting new American walls.

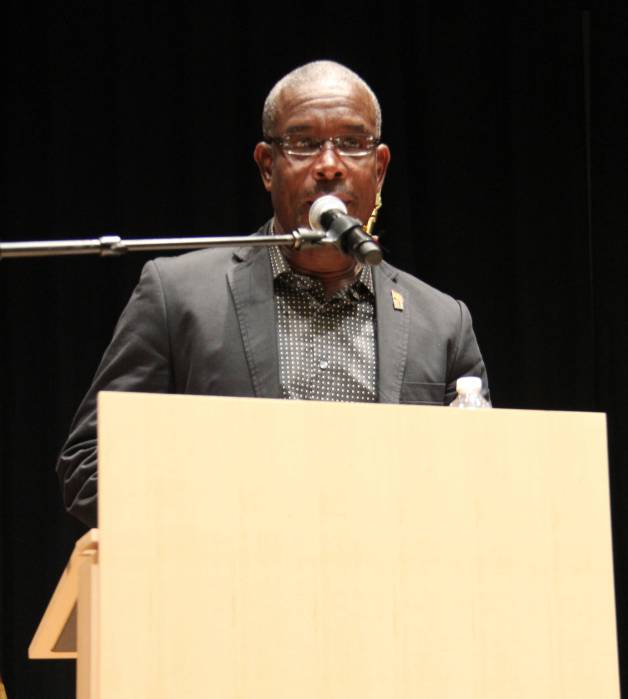

The Reverend Joseph A. Darby is pastor of Morris Brown African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.