Almost 53 years ago, Medgar Evers, the civil rights activist who led the movement to desegregate the University of Mississippi, died at the hands of an assassin as he fought for basic rights, including the right to a fair and equal opportunity at a decent education. The selfless determination of Medgar Evers and Martin Luther King, Jr., along with numerous unsung heroes, helped pave the way for a more just and equal society.

Yet more than a half-century later, this fight continues in the classrooms and on the streets surrounding a college in central Brooklyn bearing Medgar Evers’ name.

Medgar Evers College (MEC), part of the City University of New York, is a college of the community, serving students from local schools, many of whom are the first in their families to pursue higher education. However, the vast majority of students enrolled at MEC arrive without proficiency in English and math skills critically needed to complete their college coursework. They are starting off behind the curve, forced to enroll in remedial classes designed to bring them up to speed, churning a vicious cycle that wastes limited financial aid and has a profound impact on students’ confidence. Many students lose motivation, fail to complete coursework, and eventually drop out.

For too long, K-12 education has operated in isolation from college, with the assumption that the market will sort out the students who are destined for college. In a borough that has experienced the fundamental shifts that Brooklyn has, this isolation has left too many children behind, ultimately contributing to a cycle of poverty and lack of opportunity for thousands of families.

It is long overdue that we look holistically beyond improving one student, one class, one grade, or one school. Why not change the very orientation of education so that higher educational institutions are working with school communities from kindergarten onward? We must ensure that students get the support they need to master their coursework from year to year and the confidence needed to survive and thrive on their chosen college and career paths.

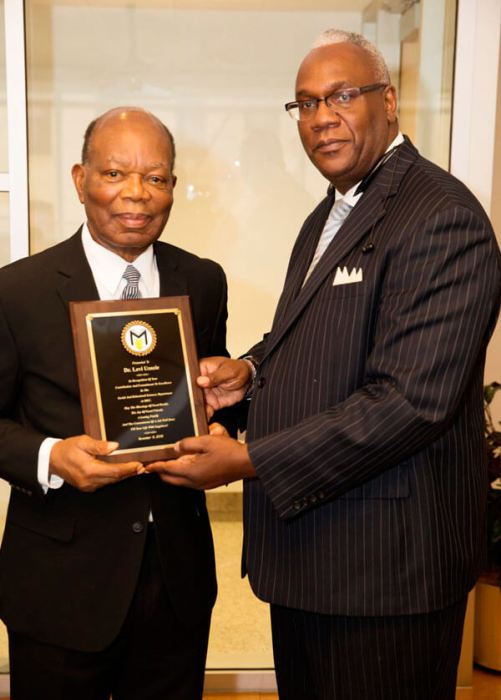

At Medgar Evers College, we are doing just that through the Brooklyn Pipeline Program, a comprehensive effort to help students from more than 80 local elementary, middle, and high schools succeed in college and then a career. What started on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day two years ago as our sketch on a cocktail napkin has evolved into a full-fledged vision. The Pipeline concept is predicated on the belief that all children are able to learn if you give them the time and resources necessary for them to catch up and connect the otherwise disjointed parts of a student’s educational experience.

In practice, the Pipeline offers a robust set of programming for students, parents, teachers, and school leaders. In summer of 2014, we launched our first Summer Institute, a six-week science and arts enrichment program that has served over 1,000 local middle school students to date. During the school year, we host Fridays at the College, a five week program held throughout the year for high school and middle school students requiring additional support in reading, writing, and math. Last week, we re-launched Computer Science Saturday, a six-week program dedicated to teaching students the basic principles of computer science and coding.

Over 300 parents have attended the Pipeline’s Parent Academy, a program designed to help parents support their children’s studies. Our monthly Leadership Seminar brings together local school principals to learn about new educational tools, curricula, and techniques that can help improve instruction and school management.

We have already seen some early success. In fall 2013, nearly 86 percent of MEC freshmen required some remedial coursework. In just the year and a half since Pipeline programming began, that number has dropped by nearly 20 percent.

By breaking down the institutional barriers between schools and replacing the K-12 structure we have relied on for too long with a kindergarten through career model, we can narrow the gap between the creators and the consumers, the rich and the poor, and those who feel a sense of belonging in college and those who do not.

Some may question what business a local college has in the academic performance of K-12 students. In fact, it is explicitly our responsibility to be concerned about student performance in kindergarten, first grade, and onward. Once students get to college, there just aren’t sufficient time or resources to catch the genie of illiteracy once it’s out of the bottle.

The Pipeline approach is a pathway to possibility for thousands of families in Brooklyn. It may even be a replicable model for other challenged communities in our city.

As we commemorate the achievements and contributions by black Americans this month, we recognize that there is much work to be done in ensuring access to opportunity for all Americans. Yet in building on the legacy of Medgar Evers, we can innovate as we educate, seizing on the opportunity each day to shift the trajectory of an entire community.