Transatlantic slave traders got their way and cooperation from some Africans because kings and other community leaders were made proverbial ‘offers they cannot refuse’ wherein they be facilitators of slavery, die, or worse yet – become slaves themselves.

Faced with threats to their lives or own enslavement and that of their community, many African kings and other leaders in sub-Saharan communities opted for cooperation with slave traders, and some even got into the trade themselves.

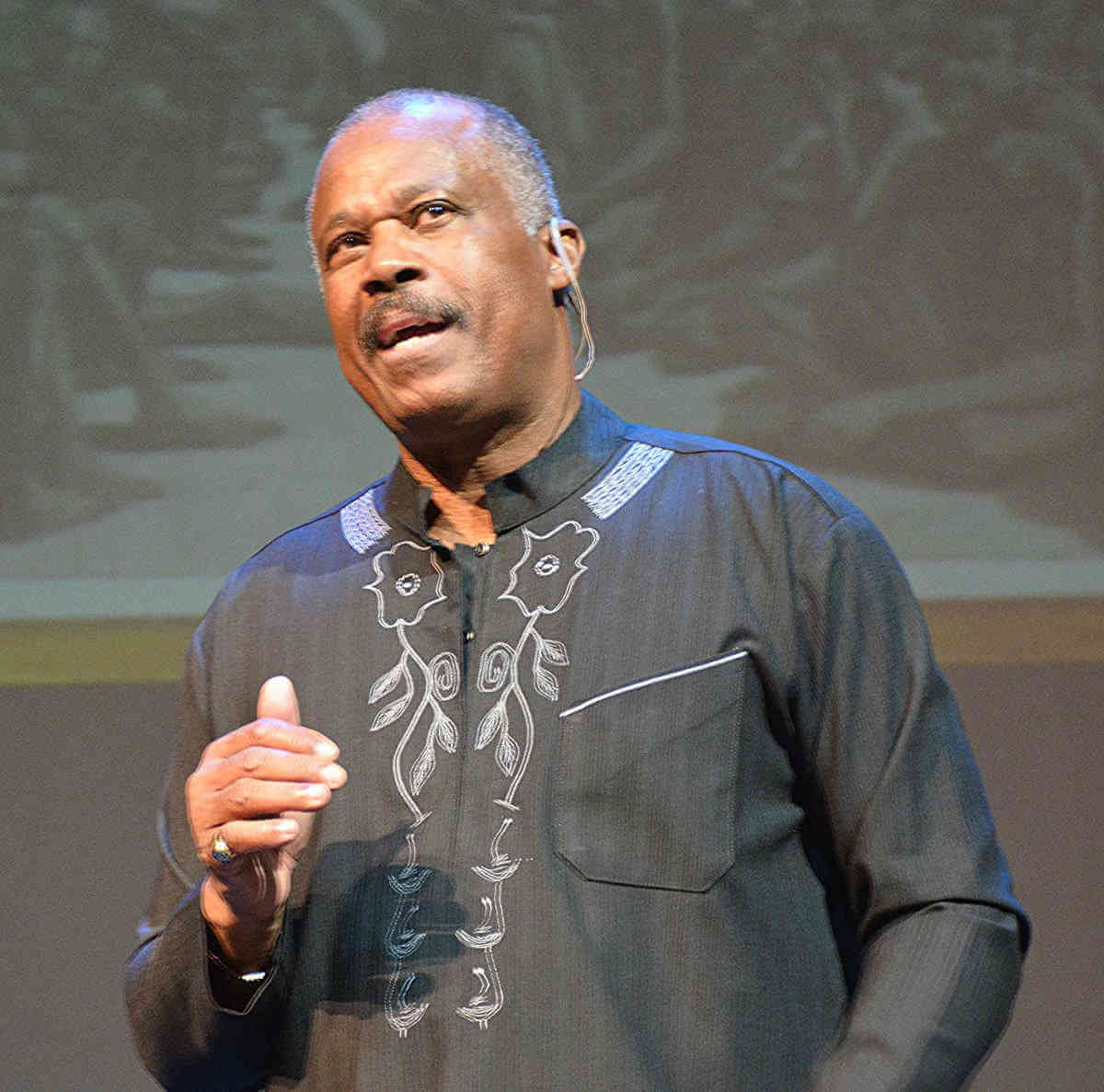

This account, recently given by University of the West Indies Vice-Chancellor, Hilary Beckles, deals with the issue of black involvement with this slave trade, a question with which many — including descendants of those who survived transatlantic slavery – have struggled to come to grips.

Beckles, a renown historian who has authored over 21 books, including 17 on slavery, said last Friday that when confronted by slavers backed with the military might of their European governments, African leaders had to decide whether to fight in battles they were sure to lose or cut deals of cooperation that would spare their immediate community in exchange for other ethnic groups.

He said that from the era from the 16th Century and over 300 years, the average king had three choices in the face of powerful slavers: 1) stand his ground and refuse to hand over fellow Africans and fight “and many of them fought and they were wiped out; 2) you could make a deal, ‘don’t take my people but you could take my neighbours’”; or 3) “don’t take my people but I will allow you access through my country. So, from the interior I would allow you to pass through my country in the way to the coast. I give you the access in exchange for not taking my people.”

His explanation was in response to a question from the floor querying why historians do not often discuss the involvement of Africans in the transatlantic slave trade.

“Those African governments were placed in the most extra-ordinary complexed environment. But most of them, if not all of them that resisted and opposed the juggernaut called the slave trade were destroyed. They were destroyed government by government.”

Beckles said that no doubt there were local participants in this slave trade, a criminal practice that comprised a triangular journey from Europe to the West African Coast then to the Americas, including the Caribbean.

“It is impossible to commit a global crime without a local partner,” Beckles said.

“But the presence of a local partner doesn’t make the crime any less evil and wicked because the global organisers of crime always have small groups of local partners.”

Explaining the complex and tyrannical circumstances African leaders faced during that slave trade, Beckles cited an example.

“We have the records of the Royal African Company that was established in 1672 to supply 10,000 Africans to the colonies in the Caribbean. It is owned by the King of England and family,” the vice-chancellor said and detailed how these slave ships of this company owned by the British royalty was accompanied by “an armada to West Africa to get those Africans.”

He said that troops from the military armada built a fort as ‘a warehouse’ for captured slaves. “The locals can’t stop them. They arrive in these small states and they tell them ‘you deliver a 1,000 of the neighbours, or we will take 1,000 of yours,” Beckles said as he pointed out that small and even some big African states were unable to confront the military might of these ‘joint stock companies.’

There followed negotiations by these kings as a matter of survival.

Beckles said that annals of the slave trade show messages from Whitehall, the seat of British government, instructing troop commanders to kill certain African kings who were found to be resistant to the slave trade.

“Instructions were coming from London to assassinate African kings who are standing in the way. We have the records. And we have the names of the people who were supposed to be assassinated.”

The Barbadian professor said, “the era of the slave trade was the era of the beginning of terrorism where African governments were terrorised.”

“Those small nations that decided to play a part were given guns to enable them to perform the role as partners,” he said, adding, “Europe’s largest export to Africa in the 18th Century was guns…in order to facilitate the slave trade.”

Beckles said that African resistance continued in many instances despite the fall of governments to the European brute force.

“The people regrouped even without leadership to fight against them.”

Pointing to an example of how “that memory still exists” among Africans, he spoke of his discovery three years ago during a visit to the southern Nigerian port city of Calabar.

“There is a very distinguished leader in Calabar whose family 200 years ago were participants in the slave trade. That family got their enrichment by being brokers for the British.

“One of the members of that family now sits in the Nigerian parliament.

“But his political seat is not in Calabar, it’s in Lagos because the people of Calabar to this day, 200 years later, have not forgiven that family,” Beckles said.

“When he leaves Lagos and goes to Calabar to his town, he comes with an armada of about 200 soldiers because he is not safe even today in his own town, because the people of Africa, they know all the families that made a deal. They know who they are.

“It isn’t that that history has disappeared.”