CODRINGTON, Barbuda, Sept. 16, 2014 (IPS) – Local fishermen are singing the blues over a sweeping set of new ocean management regulations, signed into law by the Barbuda Council, to zone their coastal waters, strengthen fisheries management, and establish a network of marine sanctuaries.

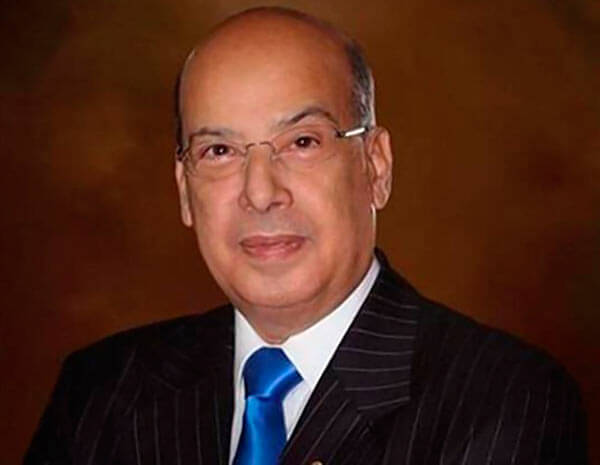

Director of the Barbuda Research Complex John Mussington has criticised the Blue Halo initiative, not for its laudable goals, but because he believes it needs a more inclusive approach that takes into account climate change and offers fishermen an alternative.

“I don’t think you are going to get the cooperation of the Barbuda fishermen,” he cautioned.

“I have been involved directly in conservation efforts in Barbuda since 1983, even more so from 1991, where every single project related to conservation of the resources, particularly related to fishing, I have been involved in, so when I speak concerning this matter I am speaking on that basis,” Mussington told IPS.

The regulations establish five marine sanctuaries, collectively protecting 33 percent (139 km2) of the coastal area, to enable fish populations to rebuild and habitats to recover.

To restore the coral reefs, catching parrotfish and sea urchins has been completely prohibited, as those herbivores are critical to keeping algae levels on reefs low so coral can thrive. Barbuda is the first Caribbean island to put either of these bold and important measures in place.

But Mussington said the regulations and the initiatives which have been signed onto are not likely to work for three reasons.

“One, the science on which the initiative is based is poor and once you have poor science to start off with you cannot expect to get good results,” he said.

“The second reason why it will be challenged has to do with the local government administration which has a track record of not adhering to regulations and a lack of will and capacity with respect to enforcing regulations.

“The third issue on which this initiative is going to likely fail has to do with the engagement of stakeholders. You cannot come into a community and basically engage stakeholders in a manner which essentially results in division and sidelining of persons. Things have not worked that way,” Mussington added.

Chair of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC, Dr. Nancy Knowlton, disagrees. She cited a recent major report based on 90 different locations around the Caribbean which clearly shows that in places where fishing is properly managed, reefs are much healthier.

“In many of these places a big part of alternative livelihoods is in fact ocean-related tourism, and in order for that to take hold you need to have a healthy ecosystem, so I am much more optimistic about the chances for the Blue Halo to be a kind of flagship for the successful management of reefs in the Caribbean,” she told IPS.

“I have been in places where there is no management, like Jamaica where I spent several years, and I can say from firsthand experience that the fishers there are extraordinarily poor and they are poor because fishing has been so badly managed that there is nothing left to catch.”

The report, which synthesised a three-year study by 90 international experts and was issued by the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), had a spot of surprisingly good news.

According to the authors, restoring parrotfish populations and improving other management strategies, such as protection from overfishing and excessive coastal pollution, can help reefs recover and even make them more resilient to future climate change impacts.

The study also shows that some of the healthiest Caribbean coral reefs are those that harbour vigorous populations of grazing parrotfish.

These include the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary in the northern Gulf of Mexico, Bermuda and Bonaire, “all of which have restricted or banned fishing practices that harm parrotfish, such as fish traps and spearfishing.”

The study is urging other countries to follow suit.

Still, according to the former president of the Antigua and Barbuda Fisherman’s Cooperative, Gerald Price, the future looks “very bleak” for Barbudan fishermen under Blue Halo.

He said the last time he checked the statistics for Barbuda, there were about 43 active fishing vessels, and each one may have three to four fishermen aboard. “What are they going to do and how are they going to make a living?” Price wondered.

“Barbuda is slightly different from Antigua in that in Antigua, our fishermen usually have an alternative. They are either a carpenter or a mason or they get work at a hotel. In Barbuda, as we understand it, they are 100 percent dependent on fishing. It’s going to be bleak, very bleak.”

Creation of the new regulations on Barbuda occurred under the umbrella of the Barbuda Blue Halo Initiative, a collaboration among the Barbuda Council, government of Antigua & Barbuda, Barbuda Fisheries Division, Codrington Lagoon Park, and the Waitt Institute. The Waitt Institute provided all of the science, mapping, and communications, offered policy recommendations, and coordinated the overall Initiative.

“I enthusiastically applaud the measures put in place in Barbuda, particularly the protection of parrotfish and sea urchins. Protection of these vitally important herbivores is the essential first step toward the recovery of Caribbean reefs from the severe degradation they have undergone in the last 50 years,” said Jeremy Jackson, director of the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN) at the International Union of the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Also included in the regulations is a two-year fishing hiatus for Codrington Lagoon, the primary nursery ground for the lobster and finfish fisheries. The lagoon, a Ramsar wetland of international importance, is one the Caribbean’s most extensive and intact mangrove ecosystems, and home to the world’s largest breeding colony of magnificent frigate birds.

But Mussington said having the Codrington Lagoon declared as a sanctuary zone will backfire.

“The cultural significance of that lagoon, the resources which are there and the history on which it is based in terms of providing livelihood and food security for Barbudans — you would understand that making such a declaration is counterproductive,” he said.

The writer can be contacted at destinydlb@gmail.com