Barbadian legislators are reluctantly pushing aside a law directing the death penalty for murder, only because the island’s lawmakers know that they are compelled to obey a Caribbean Court of Justice ruling making executions illegal.

In one of his last judgements retiring CCJ President, Sir Dennis Byron, delivered in June, the court ruled out the mandatory death sentences on persons convicted of murder in Barbados because such a practice is unconstitutional.

This ruling forced the new government of Prime Minister Mia Mottley to dust off and bring to parliament a 2014 bill amending the Offences Against the Person Act that shelves the aspect that the CCJ deemed unconstitutional but does not erase the death penalty from the statute books.

It was passed through the lower chamber of that law-making body, House of Assembly, this week. After consideration in the Senate it is expected to be proclaimed into law.

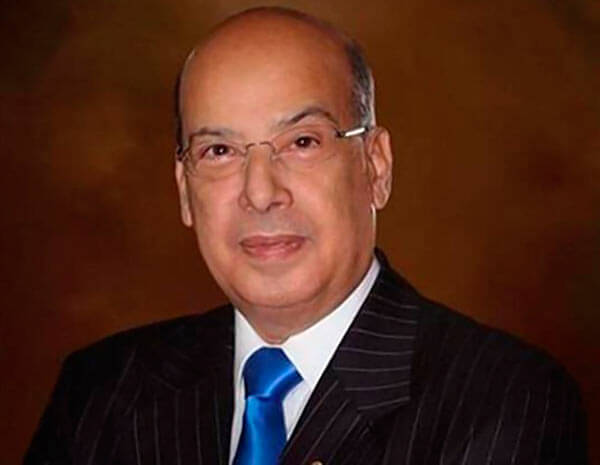

“Today Barbados has a death penalty and when this bill is passed in the House and passed in the Senate of Barbados and proclaimed to be the law of Barbados, the country of Barbados will still have a death penalty,” said Attorney General Dale Marshall as he indicated that government is not abolishing the death penalty but shoving the stipulation aside where it remains an option.

In fact, the bill to amend the act reads in part, “a person who is convicted of murder shall be sentenced to death; or imprisonment for life.”

This grudging shelving of the death penalty by these legislators, many who profess to support capital punishment, is being done only because the CCJ is the island’s court of last resort and its ruling is law of the land.

“If we choose to disobey the ruling of the CCJ on this point, what else will we choose to disobey the ruling of the CCJ on?” asked Marshall, whose government had reaffirmed in no uncertain manner its commitment to the CCJ immediately after it came to power, following former prime minister Freundel Stuart’s vow to take the island out of this Caribbean court if his party had won the elections.

Barbados was not bound by the June CCJ ruling alone, but had years earlier given a commitment to that Caribbean court and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights that it would rectify the mandatory death sentence.

This is the reason that the amendment bill to the Offences to the Person Act dates back to 2014, as the previous government had drafted it but possessed no will to go against popular sentiment on the island and legally curtail hanging.

The shelving of the mandatory death sentences in Barbados has an impact of many persons ranging from those already convicted of murders and sentenced to death, to individuals awaiting sentencing, and individuals awaiting trial for causing death of another.

“As at today, there are 62 Barbadian men and women who are awaiting trial for murder. There are six awaiting trial for manslaughter. There are 11 people on death row,” said Marshall in parliament Tuesday. “So as we speak today we have 79 people whom this statute could possibly affect.”

He explained that the 11 death row inmates will have to be resentenced in-keeping with the soon to be proclaimed amended law.

The attorney general echoed sentiments of a pro-hanging conservative Caribbean when he regrettably mused on the island’s future court guidelines on sentencing murderers.

“It must be a frightening prospect for us sir, that we have 62 people who are charged with murder but on the law as it stands, we would likely not be able to inflict capital punishment on them,” he said.