It’s black and it’s beautiful.

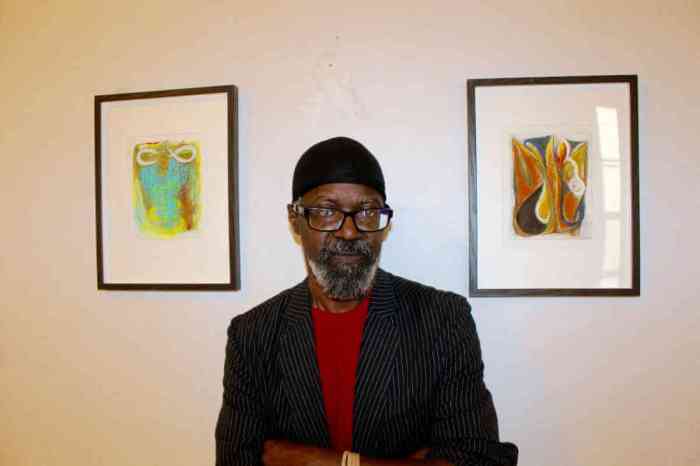

The Brooklyn Museum’s latest — and largest — exhibit focuses on the work of black artists at the peak of the Black Power movement. “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, 1963–1983,” on display until Feb. 3, features more than 150 paintings, photos, sculptures, and other forms of art produced during a significant era of black American history, said the show’s assistant curator.

“The exhibit looks at ways in which artists responded to the political moment — or did not, and the ways in which they innovated with material related to black identity,” said Ashley James.

Each room of the two-floor exhibit covers artists from a particular city or region in the United States, since movements in different areas channeled the time period in a different ways.

“There is a broad scope and a diverse range of black artists, and what they were doing during one of the most revolutionary times in American history,” she added.

For example, the Chicago-based artist collective AfriCobra painted colorful, positive portrayals of popular black figures, including Malcolm X, Angela Davis, and spiritual deities. And Kamoigne — a photography collective from Harlem — recorded everyday black life in New York.

The exhibit’s most blatantly political piece of art is a door meant to visualize the assassination of former Black Panther Fred Hampton, who was killed by Chicago police officers during a controversial raid at his apartment in 1969. In response, artist Dana Chandler brought to life “Fred Hampton’s Door II,” a bullet-riddled door with a stamp of government approval.

“That’s a really powerful work, and he used an actual door for greater emotional impact because it represents a piece of history that was extremely violent, foregrounding the action of Hampton’s killing,” said James.

Another notable piece is Betye Saar’s sculpture “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima,” which reclaims the stereotypical advertising figure and arms her with a shotgun. Saar and other artists sought to create empowering art that combated harmful portrayals, said James.

When people think of the Black Power era, they rarely think of art, but it was a key part of the movement, said James, as artist sought to express things they could not put into words.

“I don’t separate the art from the activism because in a sense, a lot of these artists were left to intersect the political ramifications of the time into their work,” said James. “This exhibit shows that there’s this sense of urgency in every single artist in it. I want people to see how these artists were working at the absolute top of their capacity under pressure to create work.”

“Soul of a Nation” at Brooklyn Museum [200 Eastern Pkwy. at Washington Avenue in Prospect heights, (718) 638–5000, www.brook