My good friend said, “And to think that one of us is among them.” I, of course, would have none of that, “us” being people of color, “them” being the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court and the uniformly noxious Justice Clarence Thomas being the one tagged for allegedly letting down the side, so to speak. “Thomas isn’t and never will be one of us,” I corrected. “He is, sadly, the foremost symbol of black self-hate of our time.”

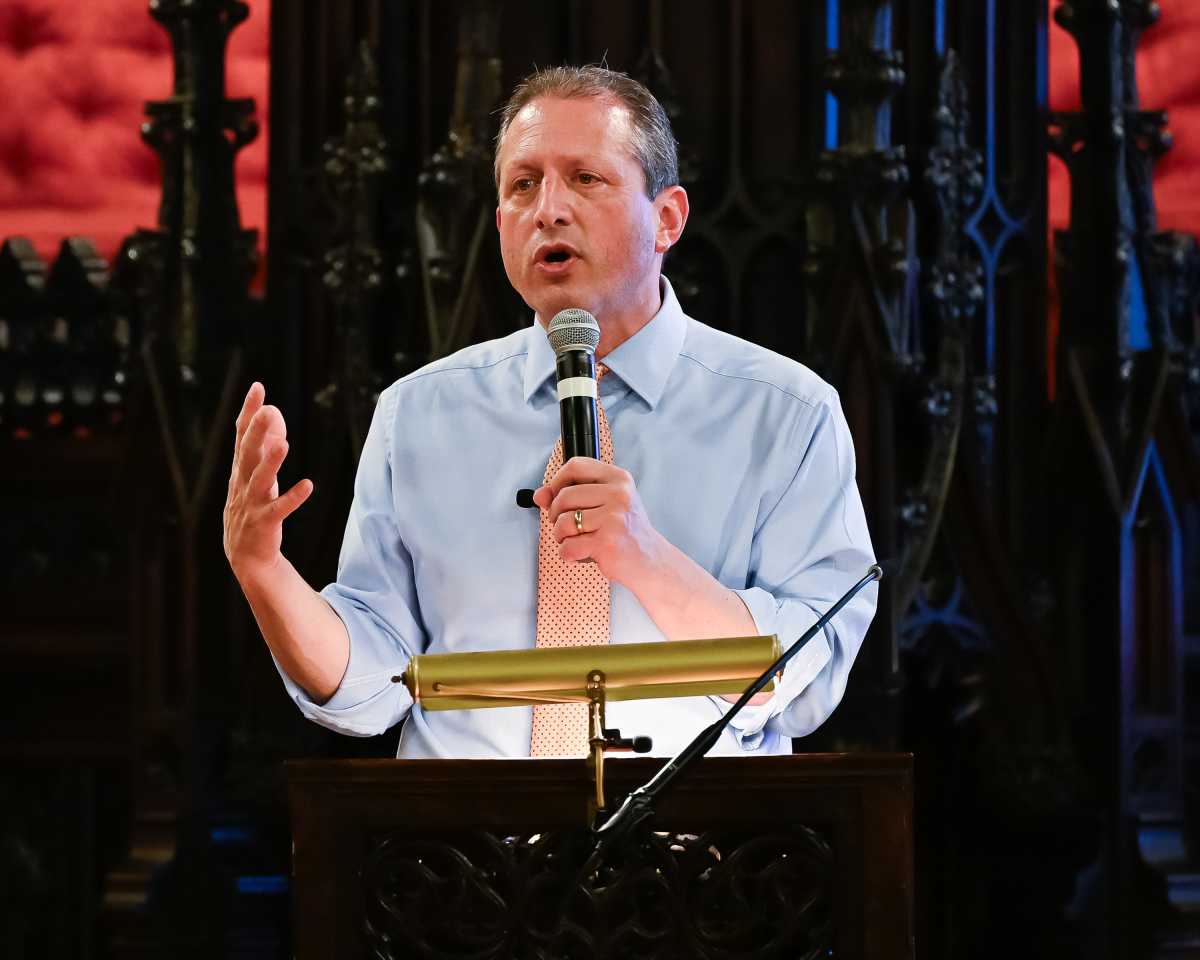

As at so many other flashpoints since his Supreme Court tenure began early in the 90s, the poke in the eye to people of color that was delivered with Clarence Thomas’ appointment bubbled up again with the court’s ruling the other day that nullified a key provision of the Voting Rights Act. In the justices’ narrow 5-4 decision, there was never any doubt that Thomas would be on the side of the conservative majority. We should be used to it by now but somehow it remains difficult, when these banner occasions come up, not to imagine what could have been and should have been, had the court vacancy into which Thomas finagled his way, been filled by an appointee more deserving of Thurgood Marshall’s seat.

Civil rights warrior that he once was, Marshall would have been particularly irked by this move to weaken the Voting Rights Act and would surely have sent packing the folks from Shelby County, Alabama who brought the action. Instead, here was Thomas, joining Chief Justice John Roberts and others on the court’s right side alignment, to declare that the lay of the land is sufficiently different from 1965, when Congress passed the Act, to dispense with the provision requiring federal oversight of election laws in certain states and local jurisdictions, primarily in the South. Roberts wrote in the majority opinion that, “no one could fairly say” that racial discrimination in elections in the areas cited approaches the pervasive and rampant practices of the time the Voting Rights Act was signed into law. Writing in the New York Times following the high court’s ruling, Prof. Richard Hasen of the University of California, Irvine, countered that if the discrimination picture had so changed, it was “because the Voting Rights Act works.”

Indeed, the premise that because voter discrimination is less prevalent, this has negated the need for continued watchdog presence by the feds, has about it a ring of naivete. One is reminded of protestations from within the very conservative bloc on the court, that the infamous Citizens United decision that opened the campaign finance floodgates would not give rise to the spending glut, which now frequently passes for the electioneering process. It’s a stretch to accept the court’s right wing being persuaded that, left to their own devices, those who had once routinely disenfranchised minority voters would voluntarily hew to the path of moral rectitude in the feds’ absence.

Reportedly, opponents who had championed this action by the court, referenced the election of the country’s first African American president as evidence of the kind of revolutionary social progress that made no longer necessary the provision for preclearance from the justice department for election procedural changes. That contention falls flat when one considers that, were it left to the nine states covered by the preclearance requirement (with the possible exception of only Virginia), America would yet be awaiting the historic election result of 2008. The court’s ruling, as reflected in the opinion written by Chief Justice Roberts, represents America, in toto, to have arrived at a place that we know, from ground level reality, it has not.

Roberts couldn’t possibly be so walled in from goings-on in the arena to be unaware of the absolute frenzy and fixation about Obama being made, without fail, a one-term president. Does Roberts really allow himself to believe that considerations of race weren’t a factor in that reckoning? Were the chief justice and any other court brethren buying into his idyllic color blindness trip secluded in some remote location when race-fueled hate mongering exploded across the country in 2009, crudely disguised as opposition to Obama’s health care reform?

Substantiation abounds of how well removed this society is from being even relatively close to a state of color blindness. The Senate, for example, has worked on and passed, to its credit, an immigration reform bill, good for garnering 68 votes in passage. The measure has however been promised a “dead on arrival” welcome in the House, where Speaker John Boehner says the Republican caucus will be fashioning a bill of its own. And with the hard-line extremists who seem to be the tail wagging that dog, it doesn’t challenge the imagination much to telegraph the likely appearance of an immigration bill masterminded by House Republicans. Color blindness won’t exactly inform the process either, given the prevailing overhang of strong anti-Latino sentiment.

As with the royal mess that was made of campaign finance in the Citizens United ruling, Roberts and his conservative colleagues will assuredly insist that theirs was the right judicial call if, as many fear, large-scale election abuse affecting minority voters follows this assault on the iconic legislation. For the chief justice, the claim will probably continue of this being close now to a race-neutral state. For the likes of Justice Thomas, we shouldn’t be surprised if he believes the Voting Rights Act was never even necessary.