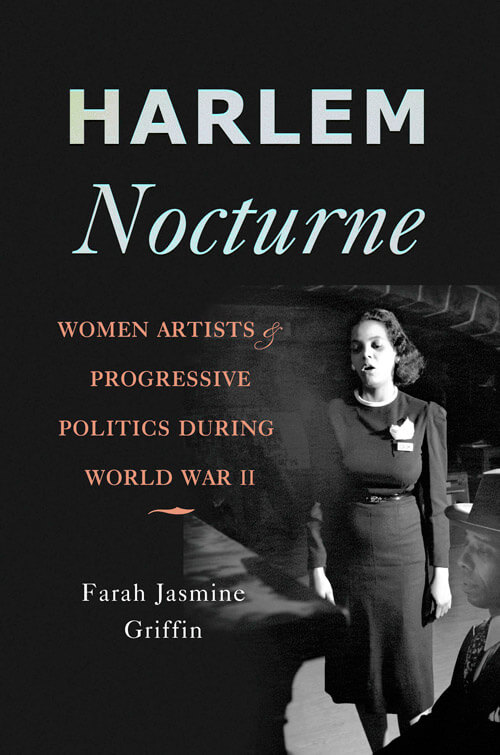

Harlem Nocturne: Women Artists & Progressive Politics During World War II”

By Farah Jasmine Griffin

c.2013, Basic Civitas

$26.99 / $30.00 Canada

242 pages

When the music starts, your feet do, too.

Oh, how you love to dance and if singing is involved, that’s even better. You sing in church, in the choir. If someone mentions it, you dance for the family. It’s a pleasure in front of friends. Heck, you’ve been known to break out in song and do a little shuffle on the street.

But what will you do with your talent? In the new book, “Harlem Nocturne” by Farah Jasmine Griffin, you’ll see how three women used theirs to change society.

In the years surrounding World War II, Harlem was a “vibrant” neighborhood, “brimming with creativity” and the sounds of Lena Horne, Lady Day, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn, Miles Davis, and Dinah Washington. It was a great time and place, if you were an artist or musician but it was “no utopia” because of Jim Crow laws, segregation, and social inequality.

Born in the Caribbean, dancer Pearl Primus immigrated to New York as a child, and though she never experienced the kind of racism that was common in the South in the 1940s, she was aware of it. Believing that dance was “a means of contributing to the ongoing struggle,” Primus used her talents including the astounding ability to jump some five feet into the air as a weapon for social justice.

Ann Lane Petry was born into a well-established and highly-educated Connecticut family in 1908. Her father was a pharmacist, her mother was a chiropodist, and they wanted Ann to follow in the family footsteps, but she had other ideas: as a “bookish, chubby child,” she had always wanted to be a writer. Harlem, for Petry, was a great place to find inspiration for stories that might affect a change in racial inequality, particularly for Black women.

Mary Lou Williams started singing and playing piano at age three and was “confidently aware of her genius.” As a member of the progressive Café Society, she “saw black music as the deepest expression of black history,” and used it to support her ideals including an attempt at creating an all-female interracial band, something almost unheard-of in the 1940s.

Though it’s filled with plenty of important history both of the national and of the entertainment kind – “Harlem Nocturne” isn’t a book for everybody.

Author Farah Jasmine Griffin takes readers for a stroll down the streets of Harlem, inside smoky jazz joints, and past the kind of educational opportunities that were available for the three women about whom she writes. I found that highly interesting, and I loved the history behind the stories, but I also thought this book was occasionally rather dry and repetitious. I wanted liveliness from these women’s lives, and that often seemed to be lacking.

I think there’s something in here for music fans. There’s something in this book for political historians, too, but I wouldn’t say this is a book you’d read for fun. Still, if you want to learn more about women and the roots of social justice, “Harlem Nocturne” will make you dance.