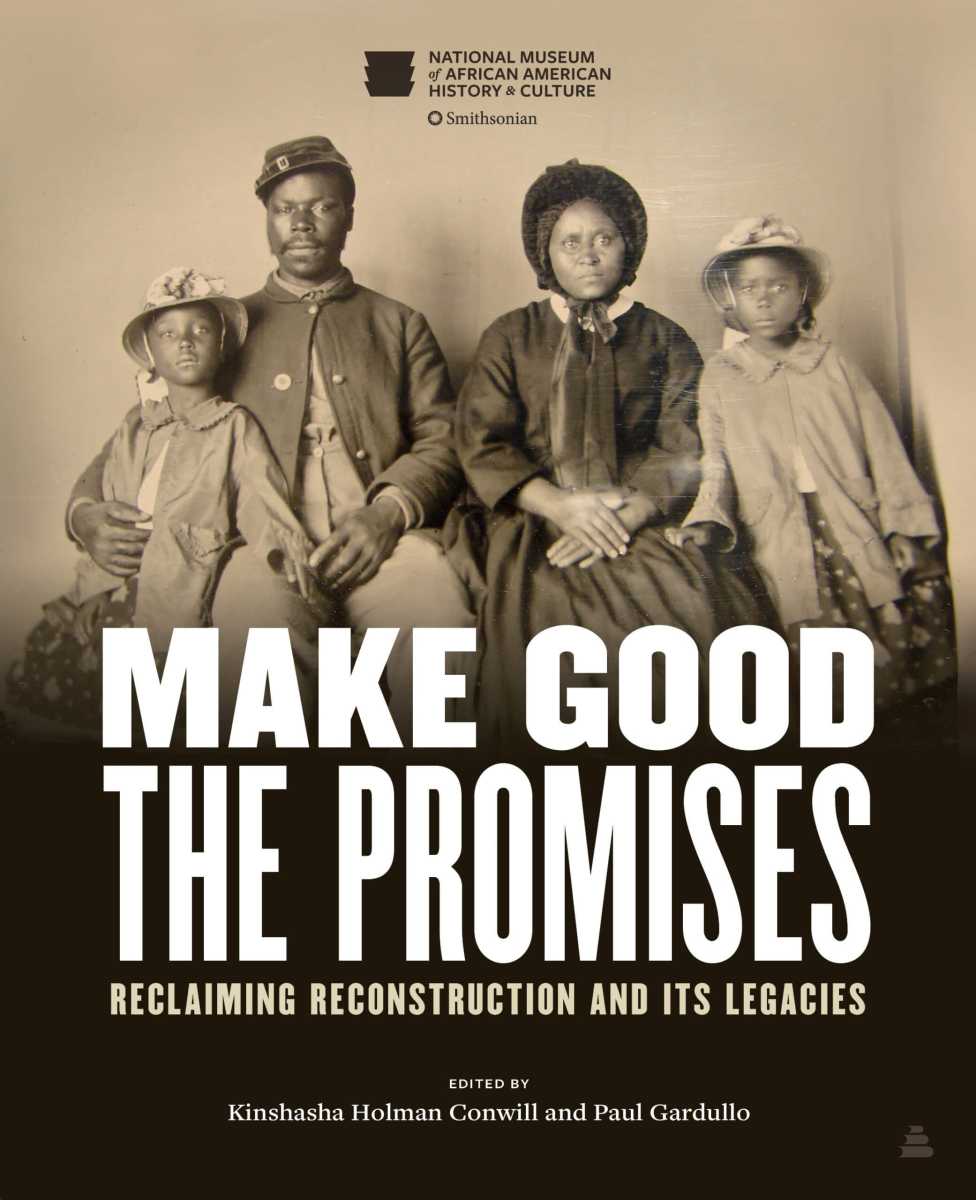

“Make Good the Promises: Reclaiming Reconstruction and Its Legacies,” edited by Kinshasha Holman Conwill and Paul Gardullo

c.2021,

Amistad $29.99 / $36.99 Canada

224 pages

Scout’s honor.

It’s a pledge, hope to die, and pinky swear. Someone’s offered their word and now you have expectations. They’ve made a solemn vow and you’ll hold them responsible but remember: as in the new book “Make Good the Promises,” edited by Kinshasha Holman Conwill and Paul Gardullo, some pacts don’t last long.

Three years before he was inaugurated, Abraham Lincoln was concerned “about the deepening crisis between the Northern free states and Southern slave states.” He “thought hard” and often about “the institution of slavery” but, though he was against it, he believed that decisions on slavery should lie within the individual states.

He’d “been in office for a month when insurrectionary forces attacked Fort Sumter,” which marked the beginning of the Civil War. Northerners leaped into the war, “believing, or so they said, that the Civil War” was not about slavery or Black people.

“Black people insisted, to the contrary, that the war had everything to do with them.”

Years before War’s end, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation gave African Americans hope that things would improve. After his assassination in April 1865 and the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment the following December, there was still hope, though Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, “proved to be an enemy of Black freedom.” Still, Johnson’s Reconstruction plan didn’t entirely undo what Lincoln had started, though it did favor Southern states in ways that made room for white supremacy and Jim Crow laws, and that still resonate today.

Johnson’s actions lingered in the fight for the vote for Black women, long after Black men were allowed to cast a ballot; it lingered in their “proper treatment as ladies…” His actions left a long legacy that began with mass incarceration and forced work, often for no valid reason. And they linger in violence and disrespect, in disenfranchisement, in segregation that still affects Black lives, and in politics and current events today. And, as the authors indicate here, reviving the subject of reparations may fix all that…

Trace it back. George Floyd back, Medgar Evers back, Rosa Parks back, Black GIs back, and you’ll see where editors Kinshasha Holman Conwill and Paul Gardullo are going. Follow it back, and in “Make Good the Promises,” you’ll find a path forward.

It’s not a new one, though, as you’ll see inside this photo-packed narrative; in fact, there’s not even just one. In the chapters that serve as refreshers on the Civil War (with focus on War’s end), there are many subtle suggestions for establishing equality. More blunt talk comes toward the end of the book, and it comes with some surprises.

Readers are also in for one big delight here: this book would be just another volume on history, were it not for the abundance of photographs. You simply must see the faces inside.

You have to see their lives.

If you’re a history buff or a reader of Civil War-era accounts, one peek inside “Make Good the Promises” will have you hooked. Pick it up, you’ll love it, cross your heart.